As we head into a new year, CORAL Senior Editor Matt Pedersen looks back and reflects on those who came before and on the notion of legacies as we offer a different sort of tribute to the sadly departed, iconic reef aquarist Jake Adams.

By every measure, the modern marine aquarium hobby is a young creature. Sure, people put marine organisms in glass vessels centuries ago, but most of the adults in the room can recognize that the captive husbandry and propagation of marine life in our glass boxes would be unrecognizable to someone just three decades ago.

I speculate that perhaps, collectively, the youth of this pastime affords the luxury of modest hubris. We audaciously propose captive arks for our coral reefs (such as the Living Coral Biobank project) while indulging in another bit of “playing God” as we crack the code of breeding corals, already excited to bend them to our whim through the time-tested propagation techniques of selective-breeding, hybridization, and environmental manipulation. Modern marine aquarists unabashedly DREAM BIG. Whether through chance, circumstance, or intent and determination, some of these aquarists will leave an indelible mark on our collective pursuits. Jake Adams, my friend and colleague whose life was cut short in October 2022, at just 41 years of age, will certainly qualify as one of those remarkable aquarists.

Of course, our collective recollection of the “who” and “what” inevitably fades, but to recycle an all-too-true idiom, we stand on the shoulders of all who came before us. While fish are “in my blood,” and corals were absolutely the lifeblood of Adams, we both shared interests beyond the saltwater world, as I suspect is true for many CORAL readers. Those tangential interests can often provide revelations of lessons learned, if only we stop to smell the flowers.

A Cross-Pollination of Interests

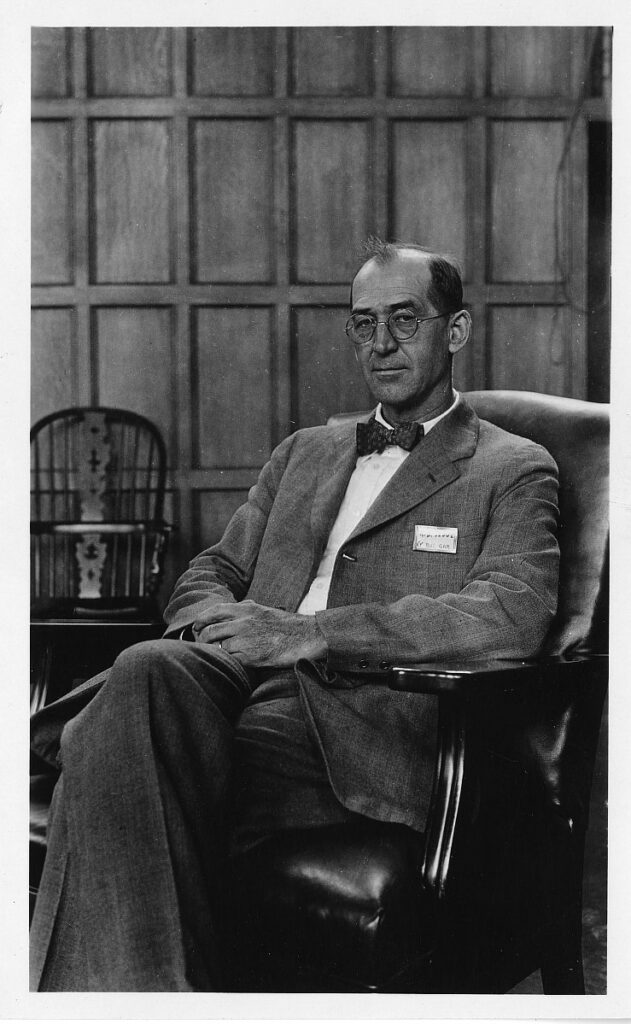

Speaking for myself, I’m certainly polyamorous when it comes to my curiosity to admire, care for, and propagate living things. My now 12-year-old son, Ethan, and I recently expanded our gardening efforts to include the hybridization of daylilies (genus Hemerocallis), an endeavor that traces its origins to the 1920s and Dr. Arlow Burdette Stout.

100 years later, A.B. Stout is regarded as the “Father of the Modern Daylily” and lends his name to the interest group’s most prestigious award, the Stout Silver Medal, bestowed to only one unique daylily cultivar each year. Stout’s legacy also includes a book, Daylilies (republished in 1986), and 130 registered daylily cultivars per the American Hemerocallis Society’s (AHS) database. But Stout didn’t simply accomplish these things; he generously inspired many more to participate and follow. The AHS currently boasts a membership of over 5,000 gardeners, and the ever-growing cultivar database contains 97,598 registration records as of late November 2022.

If one steps back for just a moment to see the bigger picture, all of our interests in living things share many parallels. Bioactive vivarium keeping is just the terrestrial version of a reef tank. Aquascaping is just gardening and landscaping underwater, and at a much smaller scale. Fragging coral is fundamentally the same as snipping clippings off a Pothos. The ornamental breeding of, say, Ball Pythons, follows the same basic concepts that can be applied to freshwater Angelfish or saltwater’s designer clownfish.

And dare I propose it, the breeding of corals, while requiring its own specialized techniques and skills, is absolutely on par with and parallel to propagating and breeding orchids and daylilies. The only real difference, when it comes to the reef-keeping world, is that the breeding and propagation of coral is still in its infancy. Daylily breeders easily have an over 100-year head-start on coral breeders!

A Legacy In Names

We are not unique, so let’s not reinvent the wheel. Jake Adams was a stickler for using the right name when it came to a coral; of course, he was primarily talking about species identity, and all the information conveyed with that name. Meanwhile, the “trade names” of corals continue to be a hotly-contested subject. It’s a bit of a wild west right now, which is how all new interest groups start out. While anyone can come up with a catchy moniker to slap on some new wild coral (or even deceptively rename something that already has a name to intentionally make it “new and rare”), this is often decried by detractors as nothing more than marketing hype.

However, there is a measure of validity to the practice. The term “cultivar” has seen use in CORAL for several years now, appropriately applied to a genetically distinct individual cnidarian and all of its asexually-propagated descendants, or clones. If cultivar names are used and respected, they trace both a lineage and a legacy, and they potentially confer a cornucopia of useful information.

Consider, for the moment, that we’re learning that many corals are not able to self-fertilize. The potential coral breeder needs to know that they have multiple genetically-distinct broodstock corals for a successful breeding project, and each one of these individuals can rightfully claim a cultivar name. These names may be nothing more than tracking IDs given to corals in a propagation laboratory; this is also the case in modern daylily breeding, where a new plant starts out with nothing more than a “seedling number”.

The best daylily individuals, those that get “introduced” and sold into the daylily hobby at large, are generally “registered” with the AHS, receiving an official and unique cultivar name. Other than the fact that corals are “not plants”, their modes of captive propagation mirror plant cultivation. I believe we should once again stand on the shoulders of those who came before us and leverage the rules already well established by the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants, making appropriate modifications if necessary for the coral breeding community.

What May Coral Breeding Look Like?

Daylily breeding has a very well-defined cycle. They flower in the summer months, and the seed is collected and processed for storage and stratification generally 6-8 weeks after a cross is made. Those seeds can be planted and grown indoors come winter, or held for spring sowing outdoors. Depending on where and how you grow, the first bloom can occur in as little as a year, but 2-3 years is more typical. By 5 or 6 years, a good plant may be a sizeable clump, and by that time, it may already be in a position to be divided, producing several or dozens of offspring that can be “released”. This cycle continues, with a new crop starting each year. The result at the other end is an annual flurry of “new introductions” that were in the pipeline for several years before being finally released to the public. These new introductions are well-anticipated, commanding high prices and going first to those that are willing to pay.

Given the seasonal, cyclical nature of coral spawning, it stands to reason the future of coral cultivation could bear a striking resemblance to the world of daylily introductions. I anticipate that, in perhaps 20 to 30 years, this could be exactly what the process of ornamental coral breeding will look like for corals that can be both sexually and subsequently asexually propagated. Coral breeders will evaluate each crop of offspring and reserve the absolute best to be grown to maturity to create the next generation. In the case of corals that can be propagated through fragmentation, the most desirable cultivars will be teased, named, and used to create larger crops of frags, ultimately to be released to eager aquarium keepers at premium prices.

While I have a love/hate relationship with the realities of “patented plants”, it is not entirely inconceivable that coral breeders may even try to apply for “coral patents” that prohibit the unlicensed asexual propagation of their cultivars, a move that would be meant to protect the investments of the propagator. Personally, I would discourage this mainly because of the headaches it creates for private aquarists, but scoff not: all GloFish are patented, and breeding them can land you in truly hot water if the patent holder finds out. Since corals somewhat ride the line between animal and plant, it’s unclear to me how the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) would treat them. Thankfully, we’re not there yet, but I believe we’ll see these issues arise and be tested in our lifetimes.

Genetic Immortality?

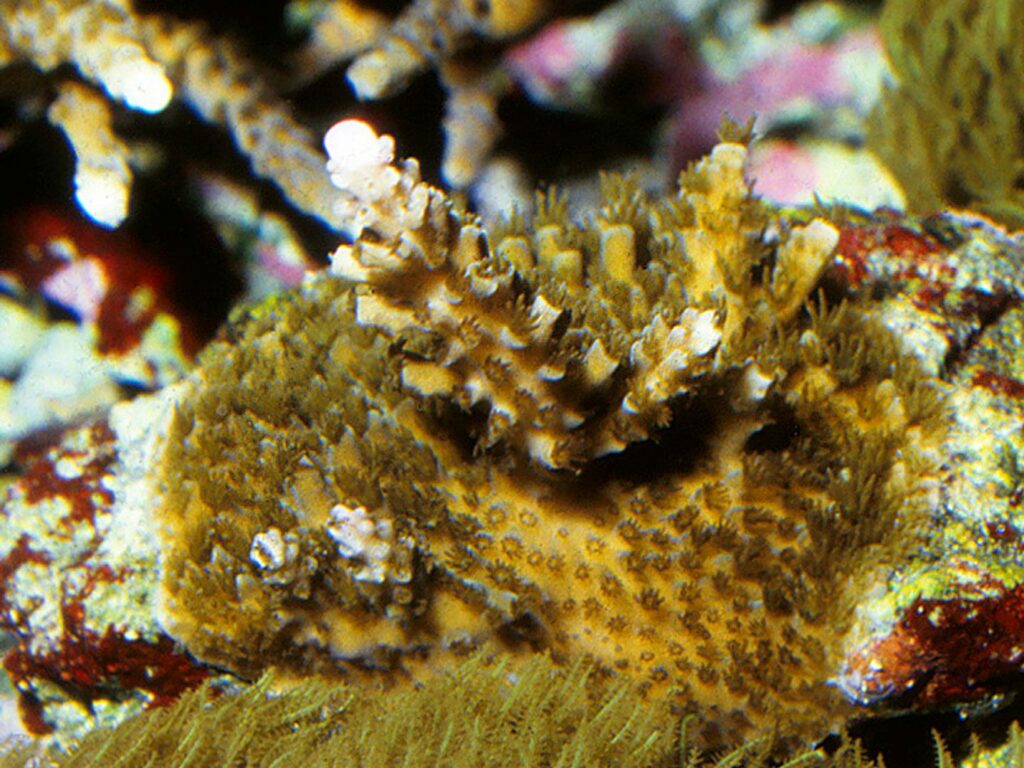

But let’s get back to that notion of the cultivar and the legacy. The asexual propagation of plants and corals creates a reality where these organisms, specifically the embodiments of their genotype, can exist indefinitely, as Dr. Ron Shimek explains in the January/February 2023 issue of CORAL Magazine. While an individual coral polyp or daylily fan may expire, the organism as a genotype lives on with seemingly no end in sight.

Not every new daylily has staying power, and many cultivars are lost over time. However, many persist. Hemerocallis fulva ‘Kwanso’, shown at the start of this article, is a cultivar of the classic orange “ditch lily” that first spread around the U.S. during pioneer times; ‘Kwanzo’ bears extra petals and was named in 1860. Spread solely through division (“fragmentation”), a plant that I currently grow is now 163 years old, and if you pay close attention, many of you might even have it in your own gardens.

One of my favorite “old time” daylilies is ‘Crimson Pirate’, a vigorous plant with brilliant red flowers created by Henry E. Sass of Omaha, Nebraska, in 1951, still actively spread among hobbyists and large-scale commercial growers.

A Living Legacy

Even the “father of modern daylilies”, A.B. Stout, is represented in the “hell strip” between the city street and the sidewalk at my Duluth, Minnesota home. The Stout hybrid, ‘Autumn Minaret’, was also introduced in 1951, 72 years ago now. In a botanical version of the “Kevin Bacon Game“, a plant that once graced Stout’s hands lives on in my gardens, and when I gaze upon it, I am looking at the same flower that first captured Stout’s attention as a worthwhile introduction. When I attempt to pollinate its flower, it is as if I am metaphorically holding the same blossoms that Stout once worked with. Stout’s living legacy persists in countless gardens around the world, and right at the end of my driveway. I am just one plant away from A.B. Stout.

The reef aquarium trade is already creating such living legacy corals without really trying. Consider the famous ‘Stuber Stag’, an Acropora cultivar with at least 38 years of aquarium history already under its belt.

In 2011, Jake Adams shared a photo of the coral, writing, “The photo [below] was made 25 years ago, on 26 June 1985, in the aquarium of Dietrich Stüber, Berlin by Svein Fosså, an internationally recognized expert in reef keeping. This historic photograph is the first known documented case of an SPS coral growing and thriving in captivity … [the Stuber Acropora] is probably the most widely distributed stony coral strain with colonies residing on every continent of the world save for Antarctica.”

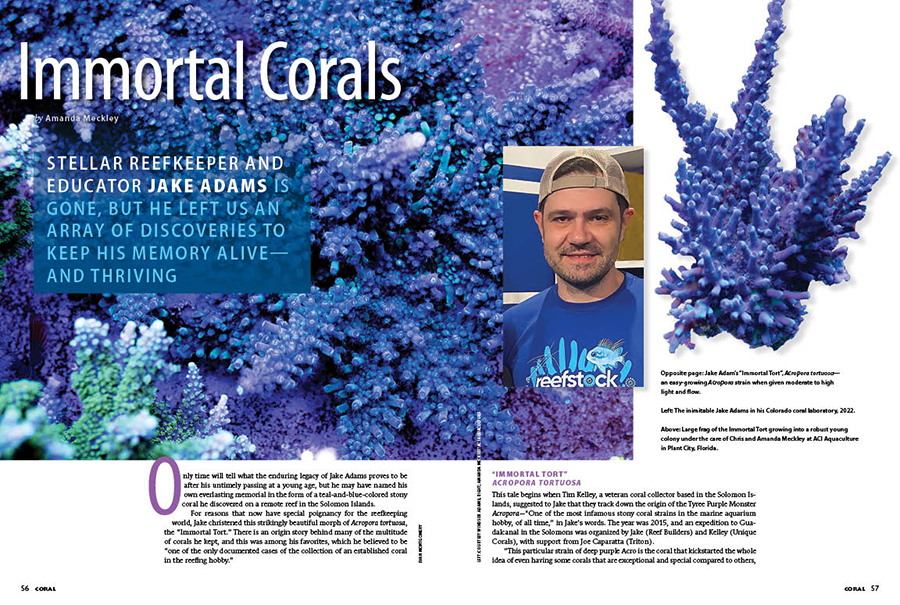

When talking with friends and reading remarks following Jake Adams’ death, I was struck by the impact that his love for “oddball corals” had among his peers. Adams, an avid diver, worked with collectors on multiple occasions to personally discover and bring a particular specimen of coral from the reef into his aquariums. Some of these corals ultimately spread through the hobby to varying extents, sometimes through the “Reefer’s Code”. Every Jake Adams coral cultivar seemed to have a rich story behind it, more so than the typical random “Indo-Pacific” locale and genus-level ID that most corals currently carry in the aquarium trade.

Born out of these conversations, the CORAL team asked ACI Aquaculture’s Amanda Meckley to gather and preserve the stories for some of Jake Adams’ coral cultivars, many of which are actively cultivated for the aquarium trade in the Meckleys’ coral farm. Amanda & Chris’s farm now unwittingly serves as one repository for some of Jake Adams’ legacy.

Amanda’s article, “Immortal Corals”, focuses on corals that are, in an indirect way, tangible pieces of Jake Adams going out into the world. Now that the stories behind them will be preserved in print (far more persistent than the ephemeral reality of information on the modern Internet), will there be corals that outlive all of us in the aquarium hobby and have a story tracing back to Jake? It seems like a pretty fitting legacy to leave behind.

Standing On Jake’s Shoulders

And this is just the beginning. Jake absolutely appreciated aquarium history as well. I believe Jake would have fully endorsed these concepts for the world of coral breeding as it grows and matures (perhaps after some vigorous arguments first, as many have rightfully pointed out). Maybe some of Jake’s most treasured corals will one day serve as the broodstock for a new generation of captive-bred coral cultivars. Will the reef aquarium hobby one day have some sort of “Craggs Award” (my nod to pioneering coral breeding researcher Jamie Craggs who I’d liken to a modern era A.B. Stout) for the best new coral cultivars released out of commercial and private captive-breeding efforts?

Jake was very intent to try to establish the concept of “fish shows” in the marine aquarium world, adopting the welcoming aspect of the freshwater hobby and trade to bring in new beginners and to showcase and elevate the work of marine fish breeders. This was just one of Jake’s never-realized ideas; perhaps someone will pick it up and bring it to reality.

Pick your cliché: “The only constant is change”, “nothing lasts forever”, “we begin to die from the moment we are born”, “get busy living, or get busy dying”. With many aquarists surprised by the truly sudden loss of our friend and reefkeeping ambassador this year, we are forced to reckon with our own mortality and the unknown limits to our own time. My closest friends and family have rightly heard me say, “I’ll die with unfinished projects”, and I’m sure that fate has come to pass for my departed friend. Having spent a particularly memorable late night going into the dawn light playing the role of moderator during a lively debate between Jake and Justin Credable Grabel at one particularly enjoyable MACNA, and knowing the seemingly endless amount of energy that Jake put into everything he did, the night owl’s defiant “Sleep When You’re Dead” mantra would have once applied to how Jake lived and worked.

Sadly, this incantation has now lost its youthful, rebellious tone for me. But Jake Adams is far from gone. While none of us will ever get to read Jake Adams’ unwritten book, his work has influenced legions of aquarists and is intrinsically interwoven into modern reef aquarium cannon. And take a look around your own reef tanks. Perhaps you already have a piece of coral that traces back to Jake, thriving in your own home aquarium. If not, perhaps you’ll seek some out for your collection.

As long as these coral cultivars persist in the hobby, so too will a living connection back to an important aquarist who lifted us all up to stand on his shoulders.

Further Reading

CORAL Magazine Remembrances of Jake Adams, 1981-2022. A collection of essays and links to other stories about Adams, housed at CORALmagazine.com. https://coralmagazine.com/remembrances/jake-adams-1981-2022/

“A Bit of Daylily History”, Charlotte’s Daylily Diary 2022: http://www.daylilydiary.com/gardenH.htm

“Daylilies: Lost Forever?”, Olde House Gardens. Stories of some of the oldest daylily cultivars. https://oldhousegardens.com/store/category/BackSoonDaylily

Having had Reef Tank for 40yers +(A. Theil, Sprung). I started Sps 3 years ago, had my ups+downs, Thanks to a guy on U.Tube my Tanks getting there. Thank You Reefers, Jake Adams. RIP. Gee UK.