Here comes the blob…

I have prided myself in that the animals in my underwater photographs are not posed or altered in any manner. As a result, the resultant image is a “slice of life”, a kind of historical record of what was photographed, a record of a tiny moment of some organism’s life history. That’s the good part.

The bad part is that by not positioning the animal, or cleaning it, or moving things out of the way, the organism is often not as clear as it might otherwise be. Still, I think the historical integrity counts for something, and particularly when I was teaching, it provided what I liked to think of as an “honest” picture of what was occurring… if only it was possible to see what that was.

As I write this, it is just after the vernal equinox, the so-called, “first day of spring,” or around here, in South-Central Montana, it would be better termed one of the latter days of winter. In the waters of the Pacific Northwest, as my last post described, there are certainly definite and easily demarcated seasons, unlike much of what is seen in the waters of the tropics. During this time of the calendar year, some interesting little animals make their most obvious appearance on some NE Pacific soft-sediment habitats.

Although they look like nudibranchs, the two snail species featured in today’s posting are most assuredly not, even if one is kind of sluggish in form and fashion. The larger of the two, Gastropteron pacificum, is a type of snail called a cephalaspidian or head-shield bubble shell, meaning it has an internal shell that looks quite like a soap bubble and is about as durable. When visible on the bottom, the pinkish-orange animal is about the size of a large grape. The sides of the animal’s foot are expanded into two long lateral lobes that are normally folded up over the animal, as it snailishly moves across the bottom. It really can’t move sluggishly, because even though it is closely related to slugs, and superficially looks like one, it isn’t one.

However, virtually nothing of the snail is, at first, normally recognizable even as an animal. It is generally covered in a mucous sheet which, in turn, is covered by adherent sediment particles. As a result, the animal is well-camouflaged, looking like nothing more than a lump of mud, and as this sea bottom habitat is covered in lumps of mud of various sizes, it is very difficult to discern. As long as it doesn’t move, that is. If it is moving, it often leaves a trail rather reminiscent of a snow plow in the very-soft layers of surface sediments.

A Gastropteron pacificum having the appearance of a stationary lump of mud. The pink structure is a fleshy, tubular, siphon that brings in breathing water.

Divers venturing into the sandy habitats in the “first and second plankton seasons”, or from approximately mid- to late-February until the end of March, could find the mud-plow trails left by these little guys as they moved around, presumably in search of food or a mate.

Gastropteron pacificum, leaving a trail in the mud as it crawls from there to here.

Gastopteron are probably detritivores, as they are reported to eat detritus and diatoms in the laboratory, but I am not sure what they eat in nature, and neither, to the best of my knowledge, is anybody else. I don’t think they have been studied in any detail which, if true, is quite a pity as they are neat little critters. When something startles them – a diver (me) in my case for the photograph, or the presence of a bottom-feeding fish, such as the dogfish, Squalus acanthias, or ratfish, Hydrolagus colliei, the little snail unfolds its foot flaps and flaps away. They

Gastropteron pacificum swimming after being startled by the author.

are quite strong swimmers and this appears to often be an effective escape response. The flapping escape response, has given the snails the nickname of Dumbo.

The NE Pacific Rat fish, Hydrolagus colliei.

This ”rat fish,” or ”chimerid,” is an elasmobranch, or a fish with a cartilaginous skeleton, but obviously it is not a shark. Individuals in this particular species can reach about 70 cm (28 inches) in length. Rat fishes are some of the most common predators in the soft-sediment ecosystems of the NE Pacific, and some of my unpublished data indicate they feed mostly on mollusks, thence annelids, and echinoderms.

This little animal is swimming away from the most fearsome and horrific predator of all, a diver – in this case, of course, me. I was sensed, probably by my water disturbances, and it then took off, and stayed waterborne for about 2 minutes. Although Gastropteron swimming appears to be undirected, given the currents in the region, it will likely cover many meters before it quits swimming and falls back to the bottom.

If the Gastropteron is successful in its life, it will find a good friend and, being hermaphroditic, they will do the snaily version of the mutually reciprocating ”wild thing”; resulting some time later in the deposition of some jelly-like ”egg masses” attached to the bottom. These are filled with small fertilized eggs (zygotes) that develop within the misnamed egg mass, which eventually dissolves releasing the larvae into the plankton.

A group of Gastopteron pacificum “egg” massess.

A group of Gastropteron “egg,” actually developing embryo, masses. I don’t know if all of these are deposited by one individual or if they aggregate during spawning to deposit the jelly-like masses (many snails in this region do form spawning aggregations).

However, they don’t get a break! There is a small slug, Olea hansinensis, in the area that searches out and eats the eggs of Gastropteron and its relatives.

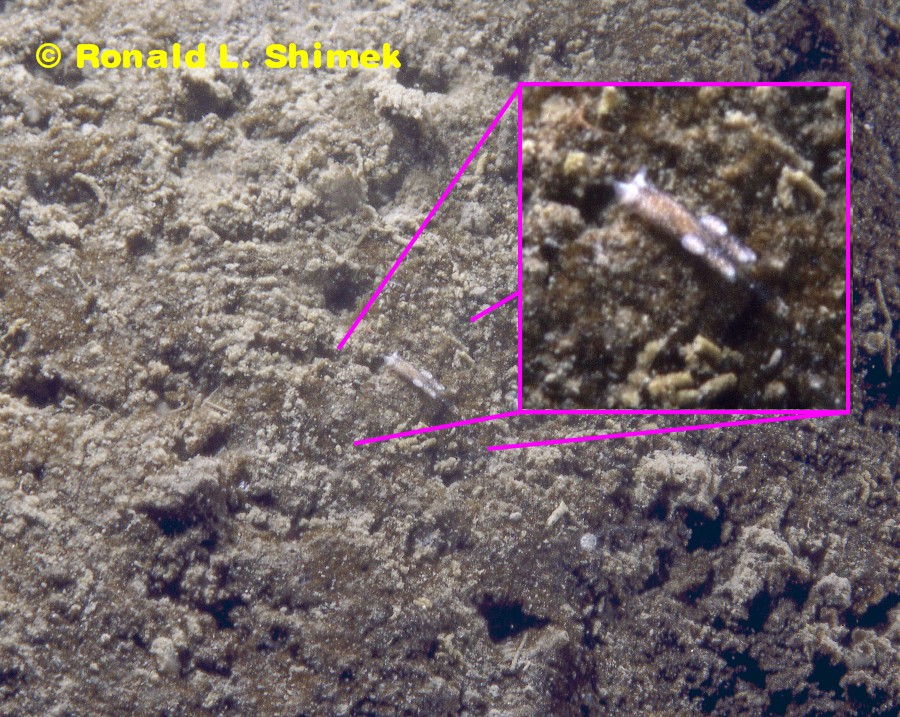

Olea hansinensis, a small slug which feeds on the egg capsules masses of Gastopteron.

Olea hansinensis. This is a small slug that eats eggs of bubble shell (= Cephalaspidean) snails, such as Gastopteron. This one was about 3 mm (1/8th inch) long, but larger individuals are said to reach about 13 mm, or half an inch in length. Although this animal looks like a small nudibranch, that is the result of convergent evolution, and while are sea slugs, they have a different sort of anatomy.

Olea belongs to a group of slugs that have teeth that look rather like soda straws that are sharpened on one end and are used to suck out the juices of algal cells. Olea hansinensis goes about getting its dinner somewhat differently, by sucking up the developing embryos of Gastopteron, turning them into something rather like the molluscan equivalent of egg nog.

I will be returning to sluggishly moving animals in a few future posts. The slug fauna of this region is rich and varied, containing representatives of several groups of nudibranchs, plus saccoglossans, some more head shield slugs and a few others. Until then…

Cheers, Ron

Gulf of mexico is full.