The only living exhibit in the Smithsonian’s Sant Ocean Hall, this 2,100-gallon reef system is seen by millions of visitors each year.

By J.R. Corvison with images by Lauren Ludi

Excerpt from CORAL Magazine, September/October 2015

About eight years ago, as a young professional with a degree in construction management from the University of Florida, I found myself making a career change that would prove to be akin to a rookie ballplayer starting his first game by pitching in the final game of the World Series.

I had been asked by Jeff Turner to join the team at Reef Aquaria Design (RAD) in Coconut Creek, Florida. Following in his father’s footsteps, Jeff has dedicated his life to the marine aquarium trade, spending time as a licensed marinelife collector, aquaculturist, and livestock wholesaler, and has had an ongoing role in creating custom living coral reef aquariums for clients who want authentic aquascapes without the usual reliance on faux corals and plastic decor. Stunning examples of his work are housed in fine homes and villas, restaurants, and professional offices, where countless people encounter a real reef for the first time in their lives.

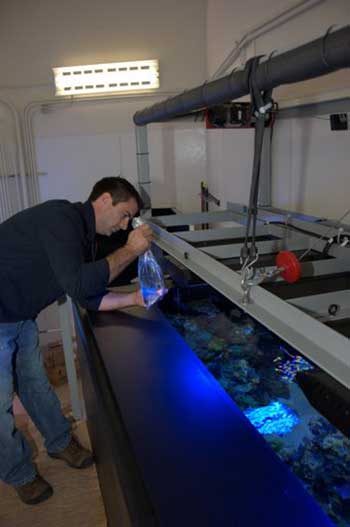

Jeffrey A. Turner of Reef Aquaria Design in 2009 working on the new reef just before its official opening. Image: Matt Wittenrich.

My first assignment turned out to be the opportunity of a lifetime for everyone involved and a dream project for anyone who loves aquariums: prior to my arrival Jeff and RAD had been awarded the honor of creating America’s highest profile marine aquarium—the Indo-Pacific Coral Reef at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC.

The museum’s original saltwater aquarium had run its course after about 15 years, and a total upgrade was planned. It was to be the only live exhibit featured in the multimillion-dollar renovation of the Sant Ocean Hall. Jeff was invited to get involved with the project after word of RAD’s impressive portfolio of large-scale living coral reef displays reached the designers.

Representing an Indo-Pacific shallow coral reef, the exhibit in 2015 contains many of the same corals and fishes originally stocked in 2009. Note 80-pound Gigas Clam, lower left, adopted by a trio of Percula Clownfish.

The original plan called for a straightforward replacement of the original aquarium, which had an antiquated life support system that would keep it stuck in the past rather than moving it into the future. Jeff thought there was a better way—using cutting edge technology and approaches from the marine aquarium hobby. Reef Aquaria Design’s work spoke for itself: its vibrant, healthy systems, many of them running for years, demonstrated what a modern coral reef aquarium could be. Instead of basing the design on the past 25 years, Jeff felt that the Smithsonian needed an aquarium that would be able to adapt to changing technologies and remain both relevant and innovative throughout the life of the exhibit. The decision makers at the Smithsonian became convinced.

Working during off hours in the huge, venerable halls of the museum, RAD crew members wheel the tank stand and components into place. Image: Matt Wittenrich/RAD.

The 2,100-gallon (7,950-L) system comprises a custom-formed, fiber-reinforced plastic (FRP) display tank (one-piece sides, back, and bottom) with a 1½-inch curved front panel made of laminated Starphire glass, a custom-designed 700-gallon (2650-L) polypropylene sump, a fully integrated 450-gallon (1703-L) water exchange system, and extensive life-support and filtration equipment, which is housed in the aquarium lab immediately behind the aquarium.

One of the first challenges was adapting the design to the irregular shape of the filtration lab space, which has curved and angled walls, no two of which are alike. The project was further complicated by the fact that the building is a registered historic landmark, so no structural alterations could be made to accommodate the weight of the very large, heavy aquarium—despite its location directly above the main gift shop. The almost 10-ton system had to fit safely within the confines of the existing structural capacities of the 100-year-old building!

Fabricated in California, the FRP (reinforced fiber plastic) display tank arrives by truck. The weight of the system, filled, totals almost 10 tons. Matt Wittenrich image.

The solution was to increase the footprint of the stainless steel structural support stand to disperse the weight of the aquarium over a larger floor area. This also allowed us to anchor a significant catwalk structure behind the main display to facilitate the ergonomic maintenance of the system. The room was laid out carefully in CAD to deal with the irregular shape. The 700-pound (136-kg) sump was carefully designed not only to fit in the space, but to provide the sophisticated filtration requirements that the system required.

With the design complete and fabrication underway in California, we made several trips up to DC from South Florida in order to attend site meetings and take field measurements. The delivery of the aquarium was an early morning affair that involved coordinating our arrival with that of the support stand, the museum’s loading dock staff, and the aquarium itself. After months and months of planning, the aquarium had spent the last week making its way across the country that it would ultimately represent. Everything was brought into the new Ocean Hall on specially constructed delivery platforms fitted with special wheels to protect the museum’s terrazzo flooring.

Working the non-public lab space behind the system, Jeff Turner plumbs the state-of-the art filtration and water management system. Matt Wittenrich/RAD photo.

Once the aquarium was in place and the filtration lab had been outfitted with water-resistant finishes, a flurry of installation and assembly work followed. A myriad of pumps, valves, PVC pipes, and auxiliary systems completed the main system. Rounding things out were a 90-gallon (340-L) mangrove estuary system, a multi-tiered coral propagation system, and a dedicated computer for data logging and remote monitoring. Each component was carefully selected and installed to create an organized and efficient work space capable of powering the display and providing a healthy environment for its inhabitants for at least the next 25 years.

Simultaneously with the design and installation process, Jeff worked for over a year to secure and organize the livestock for this unique aquarium. With 2,000 gallons of water, live sand, half a ton of live rock, and fishes and corals arriving from numerous sources, the logistics were complicated, to say the least.

The RAD crew worked overnight to create the reef base using natural limestone and live rock. Once the aquarium was filled and had run for about a week, the first corals were introduced to the newly established reef. Oceans, Reefs & Aquariums (ORA) worked on culturing several indigenous Indo-Pacific SPS coral species for use in the display. The specimens were grown out at ORA’s coral greenhouse in central Florida over a period of about one year to ensure that the aquarium was stocked with corals of significant size. Some weeks later, shortly before the dust cleared from the newly renovated Sant Ocean Hall and the public was welcomed in, Indo-Pacific fish species were sourced and quarantined through A&M Aquatics, a MAC-certified ornamental marine life wholesaler in Michigan, to ensure that only responsibly collected, healthy specimens were utilized.

Dr. Matt Wittenrich stocks Synchiropus spp. mandarinfishes into the exhibit prior to opening, using his own captive-bred stock raised in Florida.

“It was awesome being involved with supplying healthy, responsibly collected and transported reef fishes for this project,” says Bill Backus of A&M, recalling the process. “We were confident that the RAD crew was building a quality home for these guys to grow into for years to come.” The fishes were introduced in three stages after a 90-day quarantine. A&M also provided aquacultured corals that were fourth-generation examples grown for a year from broodstock that was maricultured in its country of origin. As a special bonus, RAD worked closely with Dr. Matt Wittenrich, who was engaged in pioneering work with captive-raised mandarins and delivered some of the very first aquarium-bred Synchiropus spp. on the planet to the project. These mandarins continue to inhabit the display aquarium to this day and reportedly come out to spawn in the evenings.

A great system is only half of the equation. Every aquarium requires maintenance, and a system of this magnitude, and one this visible to the public, requires expert care. After about a year of tinkering and adjusting to get the water chemistry and service protocols in perfect balance, RAD enlisted the help of Phil Wind of Reef eScape in Virginia. While we have our own in-house aquarium maintenance professionals, we feel that out-of-state care is best provided in conjunction with local service providers.

Phil Wind of Reef eScapes feeds the tank from a catwalk behind and above the exhibit. Lauren Ludi image.

“We design, install, and provide ongoing maintenance for hundreds of aquaria in the greater DC area, most with live coral, and our very favorite is the Indo-Pacific Reef exhibit at the Smithsonian,” says Wind. “The experience we’ve gained over the years of maintaining this aquarium, and the opportunity to collaborate with the Smithsonian, Reef Aquaria Design, and the scientific community, have been invaluable learning tools [that] we apply to our other projects.”

With millions of visitors every year, responsibilities to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and the medical care overseen by Dr. Brent Whitaker of the National Aquarium in Baltimore, every detail has to be perfect. In addition to daily checks by the museum staff, Wind and his team of aquarists visit the tank several times per week, performing maintenance and recording every aspect of aquatic husbandry. Weekly water changes of over 10 percent, preventative maintenance, keeping equipment and filters clean and working right, changing light bulbs and RO/DI filters on

schedule, testing water parameters, and feeding the fishes are just some of the many tasks that must be done.

The reef at its grand opening in 2009. Compare to image below to see how planted frags have filled in the reefscape. Image: RAD.

“With so many people and an aquarium that is so interesting and exciting, just cleaning the outside glass could be a full-time job, but each of those fingerprints is proof of how much people appreciate this gem,” Wind says.

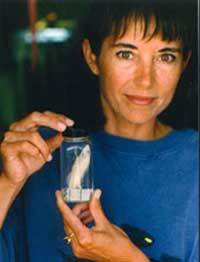

Dr. Carole Baldwin, research zoologist at the Smithsonian’s Division of Fishes, welcomes all aquarists to visit the Sant Hall Exhibit.

While service is a vitally important piece of the puzzle, the stars of the show are the aquarium inhabitants themselves. Dr. Carole Baldwin, Curator of Fishes at the museum, has some insight into what the aquarium means to the museum and to the aquarium trade as a whole.

“The aquarium allows people to see a living coral-reef ecosystem up close. Admittedly it’s one tank, but we have more than seven million visitors each year, so that one tank is important. People take care of what they care about, but they can’t care about it unless they know about it. Seeing a coral-reef ecosystem first hand gives them that knowledge. There is always a crowd around that tank!”

Dr. Baldwin balances this appreciation of her aquarium with caution. “My overall opinion of the aquarium trade is that it serves a valuable purpose in bringing to light what most people can’t see for themselves in the wild. But as with any kind of resource harvesting, the trade needs to keep conservation of natural resources in mind.”

“Just come and visit when you are in Washington!” says Dr. Baldwin, inviting CORAL readers to see the reef for themselves. “The museum is free, and there are incredible exhibits throughout,” she says.

Rampant growth of Frogskin Staghorn Acropora, supplied as frags by ORA six years ago, attests to the health of the Smithsonian system.

The aquarium has now been in continuous operation for over six years, and I have a greater respect for and understanding of what we set out to accomplish all those years ago. We wanted to create something that we could be proud of, something that would inspire the next set of individuals to take ocean conservation and aquarium-keeping to the next level. Seeing little mandarins swimming around amongst huge SPS colonies, which are continually trimmed to allow light to reach the 80-pound (36-kg) Gigas Clam on the bottom, makes you realize that this living reef is a symbol of our own growth. Whether it’s the Smithsonian’s 169-year history or the careers of our team members and everyone who helped design, build, stock, and maintain the exhibit, we have all grown and changed because of this one reef tank.

A favorite of museum visitors and staffers alike, this Vlamingi Tang helps the Smithsonian bring countless visitors face to face with their first living reef animals. Lauren Ludi image.

Jeff Turner sums it up this way: “It really was a tremendous honor for RAD to be selected to design and create this system, to know how many people see it every year, and to hear it described as ‘America’s Reef Aquarium.’ Working for the Smithsonian is a true privilege not bestowed on many. This project has truly been a lifetime milestone accomplishment for us, and when you see all the kids and their parents peering into the tank, you realize how many memories it creates for people and how important it is as a living, evolving educational tool.”

SOURCES

Sant Ocean Hall – Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History

Reef Aquaria Design