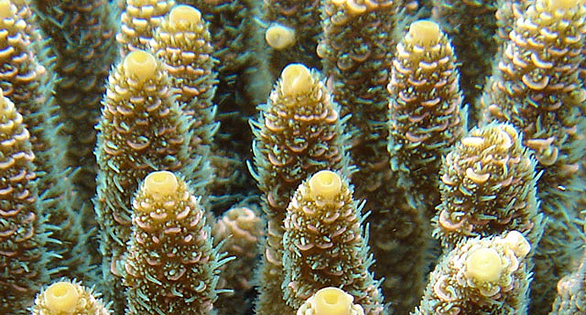

A diver surveys temperature-tolerant corals in the Great Barrier Reef (Credit: Ray Berkelmans, Australian Institute of Marine Science.)

“This is occasion for hope and optimism about coral reefs and the marine life that thrive there…”

Stony corals are already finding ways to survive in warming seas, according to new research by an international team of scientists from the University of Texas, the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), and Oregon State University.

Studying stony corals on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), they discovered that some coral populations already have genetic variants necessary to tolerate warm ocean waters. Furthermore, the researchers speculate that humans can help spread these genes as climate changes unfold and threaten the existence of coral reefs as we know them.

Far Northern Great Barrier Reef. Reefs around the world are threatened by climate change. A new study shows that some corals have the genes to adapt to warmer oceans. Credit: Line K Bay, AIMS

The discovery has implications for many reefs now threatened by global warming, and it shows for the first time that mixing and matching corals from different latitudes may boost reef survival, according to the findings published in the journal Science.

The researchers crossed corals from naturally warmer areas of the northern Great Barrier Reef in Australia with corals from a cooler latitude 335 miles to the south. (The northern GBR is closer to the equator and warmer than the southern GBR.) The two groups of corals are separated by about 5º of latitude.

The scientists found that coral larvae with parents from the north, where waters were about 4º F (2º C) warmer, were up to 10 times as likely to survive heat stress, compared with those with parents from the cooler waters to the south.

Dr. Line K. Bay, lead author of the new paper, with an Acropora colony in the Australian Institute of Marine Science labs in Townsville. Image: AIMS.

Using genomic tools, the researchers identified the biological processes responsible for heat tolerance and demonstrated that heat tolerance could evolve rapidly based on existing genetic variation.

“Our research found that corals do not have to wait for new mutations to appear. Averting coral extinction may start with something as simple as an exchange of coral immigrants to spread already existing genetic variants,” said Dr. Mikhail Matz, an associate professor of integrative biology at The University of Texas at Austin. “Coral larvae can move across oceans naturally, but humans could also contribute, relocating adult corals to jump-start the process.”

Worldwide, coral reefs have been badly damaged by rising sea surface temperatures. Bleaching (a process that can cause widespread coral death due to loss of the symbiotic algae that corals depend on for food) has been linked to warming waters. Some corals, however, have higher tolerance for elevated temperatures, though until now no one understood why some adapted differently than others.

“This discovery adds to our understanding of the potential for coral to cope with hotter oceans,” says Dr. Line Bay, an evolutionary ecologist from AIMS in Townsville and joint senior author on the paper.

Potential applications of the findings

• Choosing heat-tolerant corals for artificial propagation and reef restoration

• Identifying reefs with heat-tolerant coral communities and protecting them so that they can naturally repopulate other reefs

Dr. Bay says, “Before such steps are considered, we need to learn much more about coral adaptability to be able to discriminate between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in the game of climate change. One of the first tasks would be to confirm the role of mitochondria in heat tolerance, which was suggested for the first time by this study.”

The study also suggests that “Mum is best,” said the researchers. Coral larvae had up to a ten-fold increase in their chances of surviving heat stress, of which five-fold was contributed by the mother. A possible explanation was provided by genetic analysis: tolerant larvae had altered expression of genes working in mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cells that are inherited solely from female parents.

Reef-building corals from species in the northern Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea are similar to those used in the study. There, too, reefs may benefit from conservation and restoration efforts that protect the most heat-tolerant corals and prioritize them for any restoration initiatives involving artificial propagation.

“This is occasion for hope and optimism about coral reefs and the marine life that thrive there,” Matz said.

In addition to Matz and Bay, the study’s authors were Groves Dixon, Sarah Davies and Galina Aglyamova at UT Austin, and Eli Meyer of Oregon State University.

The study was supported by funds from the National Science Foundation and the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

More photos of coral reefs and information about the study can be found at this UT Austin slideshow.

Read More: Background Information on Coral Genetics and Heat-Stress

Genetic rescue can save corals from warming oceans

Coral bleaching is a serious threat to the future of coral reefs, according to marine researchers and the Great Barrier Marine Park Authority. It occurs when high sea temperatures cause the loss from corals of the symbiotic algae that provide most of their food and, incidentally, their colour. While bleaching can be temporary, at best it causes long-term reductions in health, and at worst widespread mortality.

Rising sea temperatures precipitated by global warming are likely to cause further declines in coral cover, and extinctions of local populations – and possibly of species – within this century. The good news is that even modest change in stress tolerance (i.e. through the process of adaptation) can vastly improve the outlook for reefs.

Acropora millepora, a widespread species with local populations that are more heat-resistant than others. Image: Mikhail Matz.

The fundamental building block for adaptation is biological variation, and temperature tolerance is a variable response. Coral species suffer to different degrees, and within species some individuals and some locations are less affected than others. Corals from naturally warmer reefs, for example, can cope with warmer temperatures than corals from cooler reefs. It might be possible to avoid bleaching and subsequent mortality from projected temperature increases on cooler reefs through the introduction of heat-tolerant corals from naturally warmer reefs. But this can only work if the variation in heat tolerance is heritable – meaning that offspring resemble their parents and not the environment in which they are born.

In the study published today in Science, researchers crossed corals from naturally warmer and cooler locations on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) more than 500 km apart and distinguished by an average two degrees in temperature. The work provides new insights into the mechanisms that underpin temperature tolerance in corals.

The researchers demonstrated up to a ten-fold increase in the odds of survival of coral larvae under heat stress when their parents came from a warmer lower-latitude location. This directly demonstrates that temperature tolerance is heritable: parents that tolerate higher temperatures have offspring that do so, too. This means that a potential solution to the problem of coral bleaching already exists in natural populations. If more tolerant corals can spread their genes to locations impacted by bleaching, either naturally through larval dispersal or with the help of humans moving adult corals, then some of the negative effects of global warming can be averted. This mechanism of adaptation based on existing genetic variation is termed “genetic rescue.”

It has been suggested previously that coral thermal tolerance can be triggered by a pre-emptive stress response that makes an individual “primed” for stress. The results of this study do not support this idea. On the contrary, the researchers showed that more tolerant individuals exhibit less, not more, of a stress response before the actual stress is applied.

Coral larvae inherited expression of more than 2,700 genes directly from their parents, equally from mother and father. Still, larval heat tolerance was mostly due to mother’s influence: of the ten-fold overall increase observed in the experiments, five-fold came from mother. By analysing the heat-adapted offspring further, the researchers identified two regions of the genome that were important for heat tolerance, which happened to encode proteins destined to work in the internal cellular powerhouses known as mitochondria. Since mitochondria are inherited solely from the mother, this provided a reasonable explanation of elevated maternal influence on heat tolerance. The role of mitochondria in coral heat tolerance has not been considered previously, and the authors’ next task will be to verify this novel hypothesis.

In summary, the study shows that variation in thermal tolerance of corals across latitudes has a strong genetic basis that can serve as raw material for natural selection and, hence, evolution.

The researchers crossed individuals of the common branching coral Acropora millepora from Princess Charlotte Bay on Cape York Peninsula, 180 km northwest of Cooktown, with those from Orpheus Island, about 75 km north of Townsville. There is about 5° of latitude and 540 km between the two.

Media resources including background information, photos, and a copy of the paper are available at: www.scienceinpublic.com.au/marine

SOURCES

Adapted from materials released by the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the University of Texas, Austin.

Thursday, June 25, 2015

Images courtesy Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Bleaching (dieing) of Corals can have many reasons.. From getting eaten by Thorn Star Fish, Parrot Fish…by over taken from more aggressive Corrals…I believe more attention must be given to Current changes, which also bring or take the Food sources (Plankton) to the Corrals. Many Corral riff’s fall try in Coastal Zones for many Hours and Corals are ex post to the full Sun and still doing well.. So Heat is a smaller Factor I believe.. Food, current, Ox-ion more imported in a Life of Corrals..

I love articles like this. There is no mention of actual water temperatures. The only mentioned waters temps were in the north reefs temperatures are 4 degree higher than waters in the southern reefs. What is the water temperatures? How much has it risen and in what period of time?

I had been basically lecturing people of this very

idea a little while previously with a business owner.

I have been at all times speculating what the ideal

time frame was to communicate those encompassing

this idea.

Hi to every one, the contents present at this website are in fact remarkable for people

experience, well, keep up the good work fellows.