Northern parts of Indonesia are currently going through a mild bleaching event (https://oceangardener.org/mild-bleaching-event-in-indonesia/). Hopefully, most corals can recover from this environmental stress.

I encountered this bleaching event while visiting some island-offshore reefs in Tomini Bay, the equatorial gulf which separates the Minahassa (North Sulawesi) and East Peninsulas of the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia. The Togian Islands lie near its center. To the east, the Gulf opens onto the Molucca Sea. It’s one of the most diverse coral zones in the world.

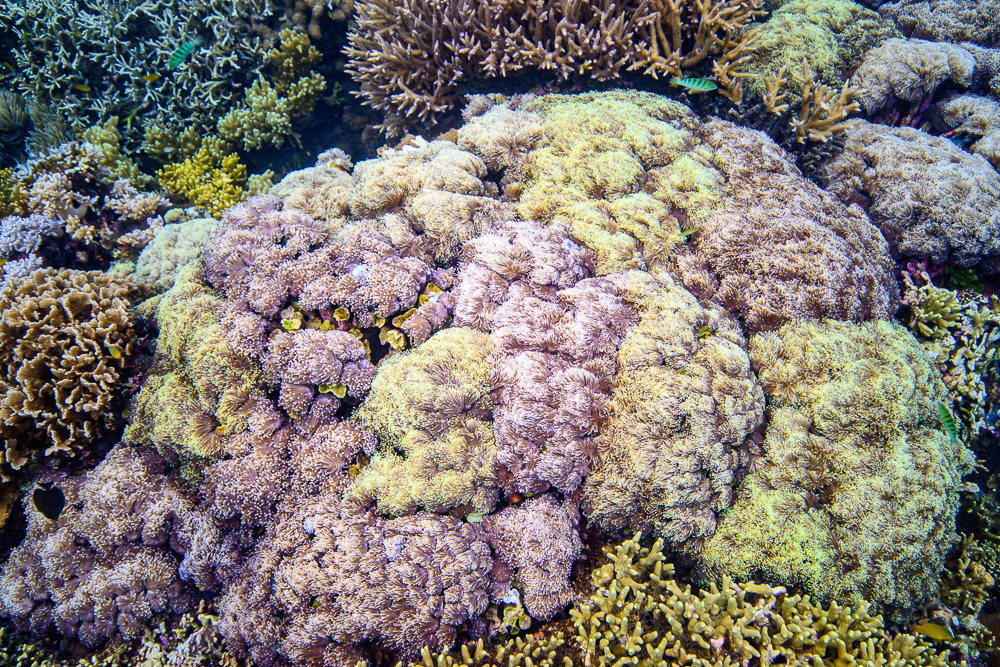

I came upon some interesting large aggregation of Torch Corals (Euphyllia glabrescens). Although it was not the most colorful one, we saw only greens and browns, but finding a large concentration of that particular species is always a treat.

A precise location on the reef:

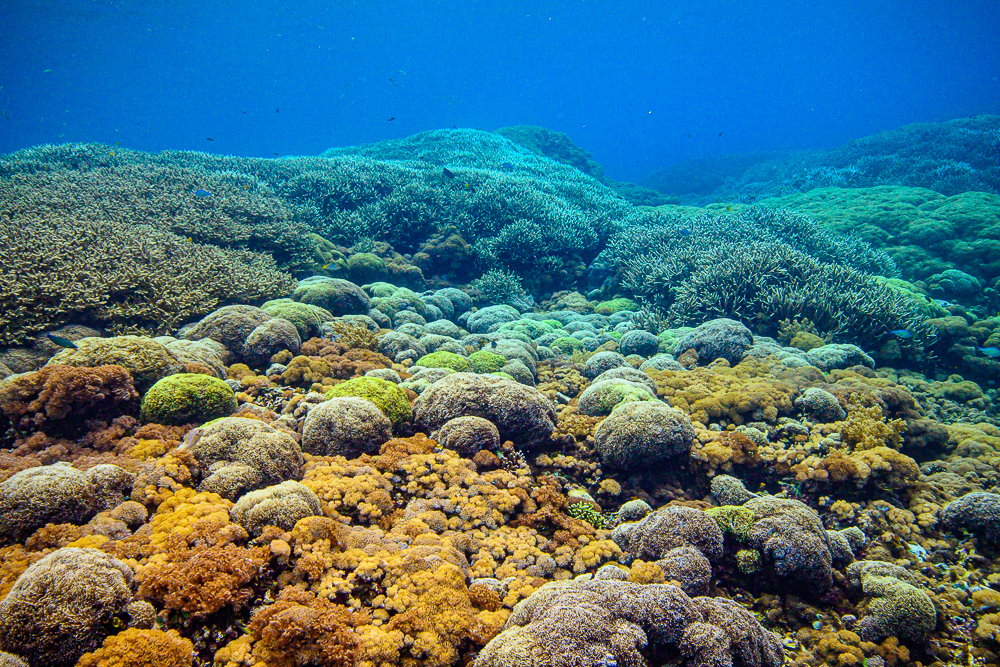

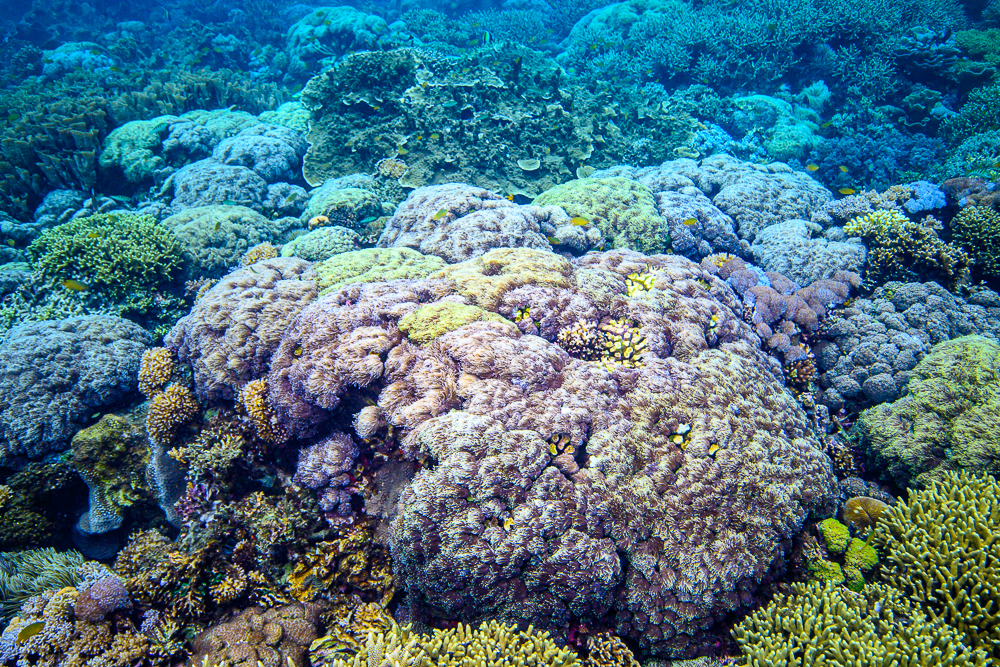

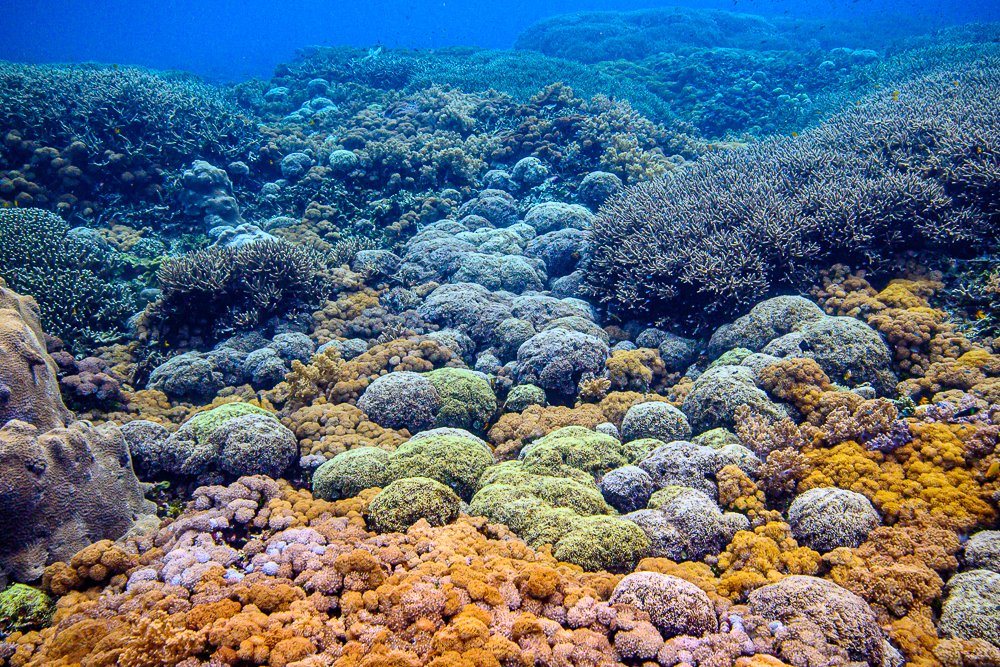

Free diving all around the small island, it was fascinating the see the changes in coral population, depending on the reef exposition to swell, depth, substrate. There are hazards in coral habitat. If a coral is found somewhere, it’s because this is where it belongs.

The corals are so well segregated, that if you understand swell and current direction, you don’t need to lift your head to know where you are. You just have to look at the corals below.

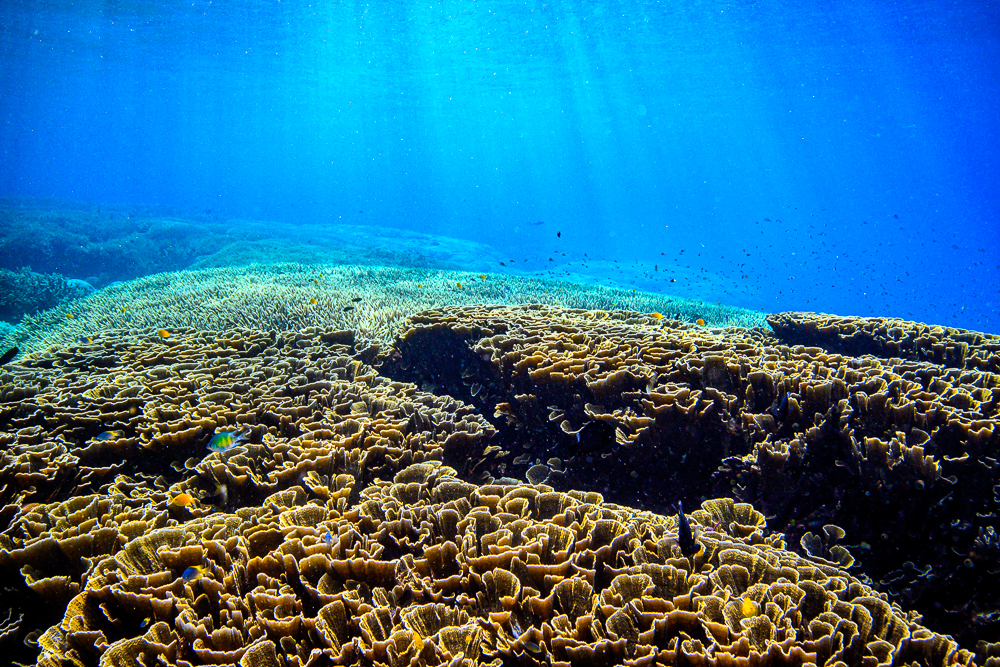

Blasted but not pounded upon:

All the Torch Corals were concentrated in two particular small spots. Specifically, these corals were found on both sides of the island, just next to and below the wave breaking point, below 3 m (12 ft) deep, where the surge is still pretty strong but away from where the waves break. And thus they found the right combination; they were blasted by surge flow, but not pounded upon by the swell.

Protected among other species:

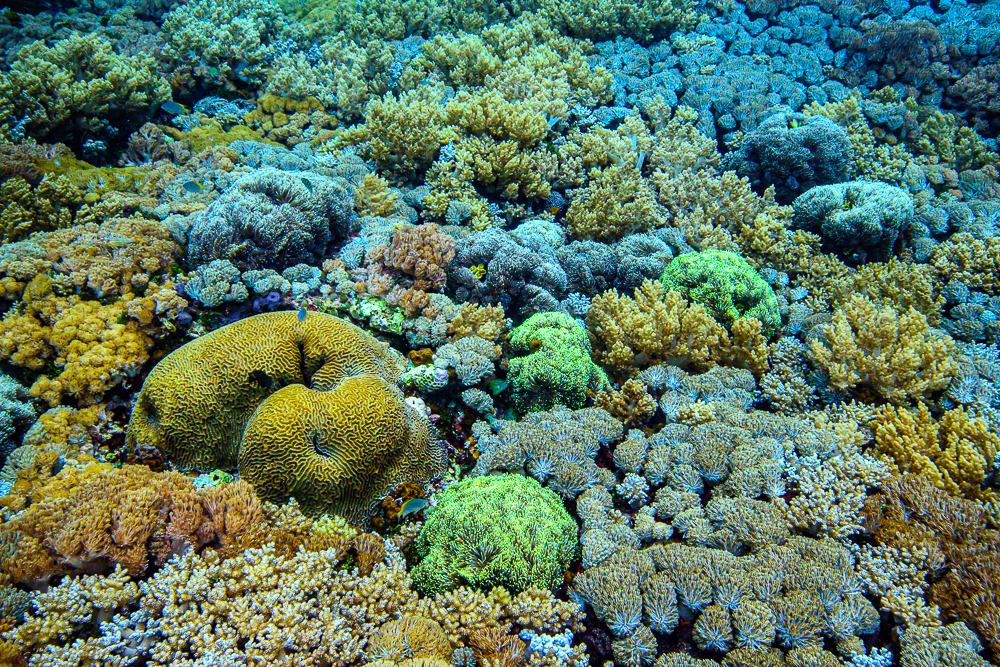

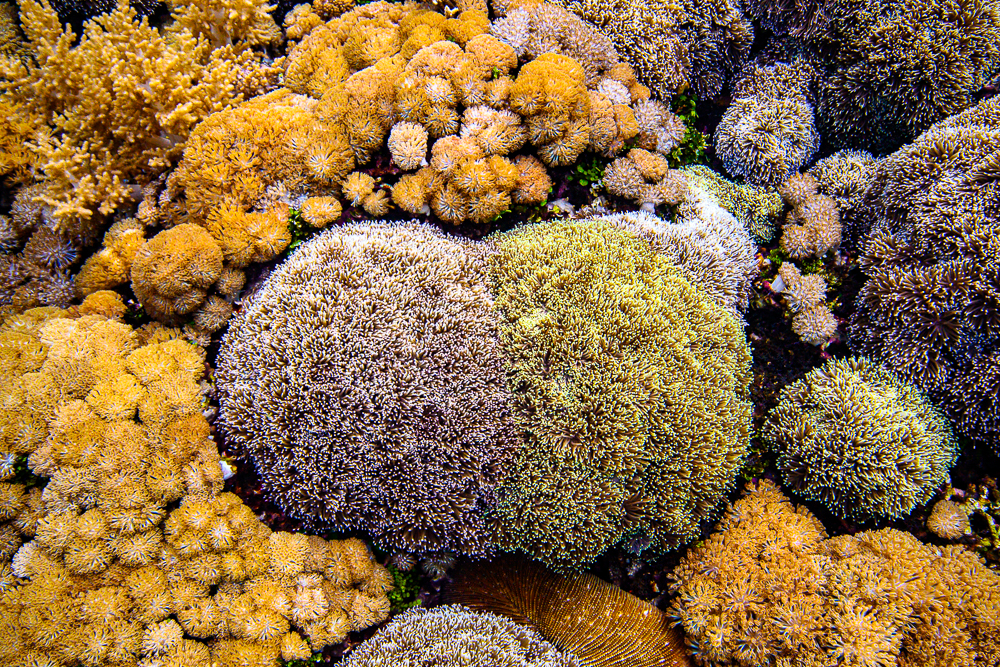

Isopora palifera and Galaxea fascicularis are usually present right below the high energy, break, and white water. Just below this tumultuous zone lies the most prime reef real estate, with large colonies of Acropora florida, A. robusta, A. damai, A. formosa, A. yongei, Montipora foliosa, Montipora undata, and Echinopora lamellosa.

Euphyllia glabrescens like the protection that can be had between large colonies of fast-growing corals. In that particular part of the reef, we found 100% coral cover. Every small, free square inch is quickly occupied by Xeniidae corals. But, they seem to serve a very important function, preparing the substrate, and binding every piece of coral rubble together so sponges and coralline algae can finish the job by cementing everything up. Thus, later, coral larvae can settle on this newly stabilized real estate.

If we swim away from the break area toward the protected side of the island, we find many other species of Fimbriaphyllia corals: F. ancora and F. paradivisa, also known as Hammer and Branching Frogspawn Corals. It’s amazing to see all of them living together in the intermediary zone.

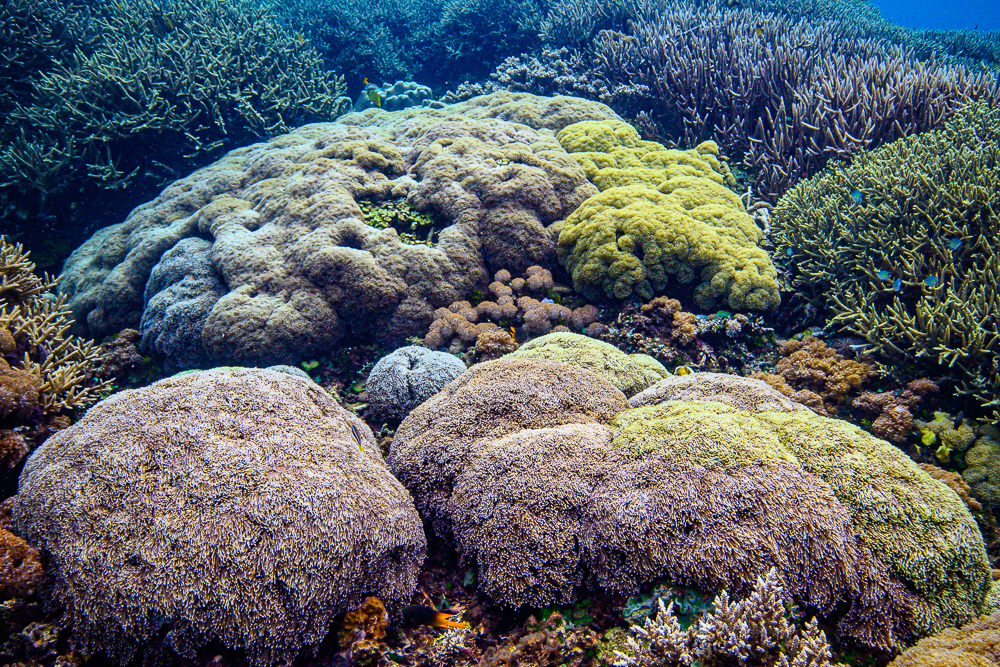

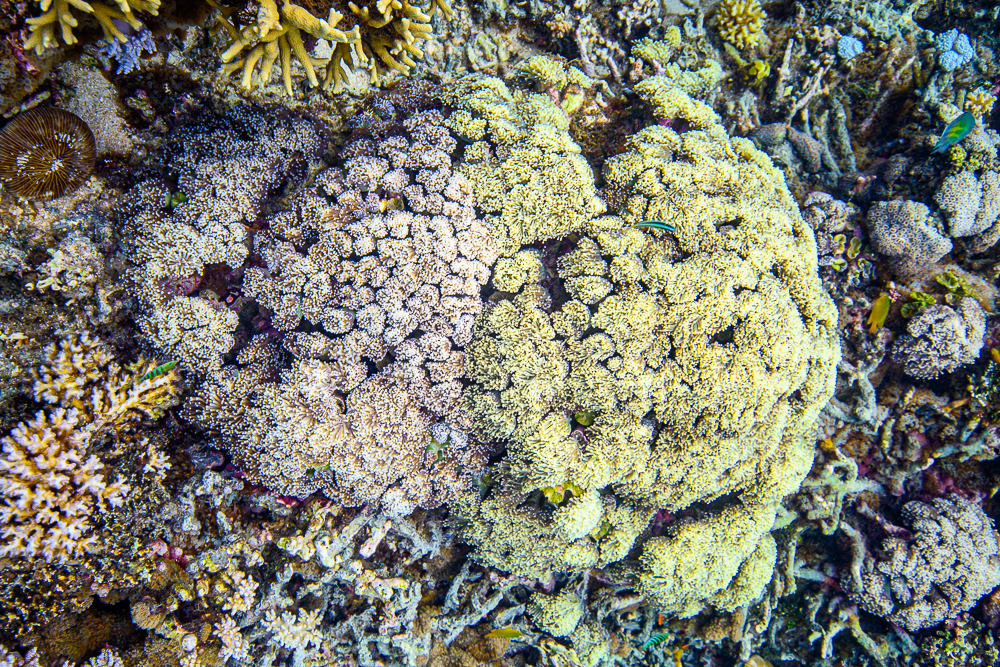

Euphyllia glabrescens doesn’t produce huge colonies:

I’ve seen colonies of Euphyllia glabrescens torch coral, in many different types of habitats, from the shallow exposed reef to deep sheltered lagoons. Sometimes they are encountered among very large colonies of hard corals from a wide range of different species.

But the biggest colony I’ve ever encountered was about a meter and a half (5 ft) wide. Even in this particular place, this was the upper limit of the norm. Most of the Torch Coral bed was composed of 30 cm (1 ft) size colonies.

One of the reasons could be that E. glabrescens is a brooding species, producing floating and sinking larvae. Many sinking larvae happen to settle just next to the parents.

Many colonies were also growing together. Mixed-color colonies, with some green and brown polyps living together and pretending to be part of the same colony were seen.

This particular reef is one of the best that I’ve been lucky to dive on. It was stressed but not enough to kill these corals just yet. Hopefully, the temperature will lower in the next weeks. Unfortunately, reefs of this caliber are harder and harder to find. Very few reefs like this have been spared from dynamite fishing in this incredibly diverse area. The reef fish life was abundant, but all the bigger fish were gone. No Napoleon Wrasses, no Barracudas, no Jacks, very few Snappers…

Amazing spot. I love this part of knowledge: “Every small, free square inch is quickly occupied by Xeniidae corals. But, they seem to serve a very important function, preparing the substrate, and binding every piece of coral rubble together so sponges and coralline algae can finish the job by cementing everything up. Thus, later, coral larvae can settle on this newly stabilized real estate.”

Thank you, Vincent