Long considered among the apex predators of the world’s seas, oceanic sharks and rays are vanishing at rate that marine biologists say is alarming and a warning that a number of species are well on their way to extinction in this century.

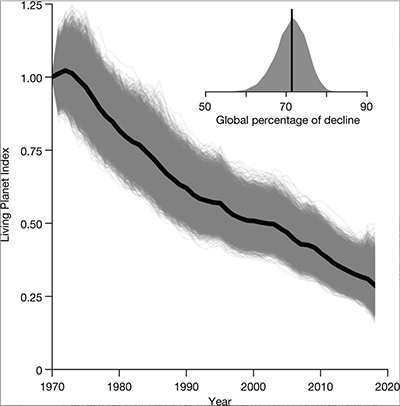

Oceanic shark and ray populations have declined 71 percent in the last 50 years, according to a new study by researchers at Canada’s Simon Fraser University (SFU) just published in the journal Nature. Among the ominous trends: larger species are disappearing faster than smaller sharks, tropical species are in faster decline than cold-water animals, and the worst losses are in the vast Indian Ocean. Previous studies have also shown that declines in shark populations correspond to perturbations of ancient food webs and the deterioration of the health of coral reefs.

With three-quarters of these iconic species now threatened with extinction due to overfishing, SFU biologist Prof. Nicolas Dulvy hopes the paper will serve as a global wake up call.

“Knowing that this is a global figure, the findings are stark,” says Dulvy, the study CORAL-author and Canada Research Chair in Marine Biodiversity and Conservation. “If we don’t do anything, it will be too late. It’s much worse than other animal populations we’ve been looking at.

“It’s an incredible rate of decline steeper than most elephant and rhino declines, and those animals are iconic in driving conservation efforts on land.”

The results were a shock even for experts, Pacoureau said, describing specialists at a meeting on shark conservation being “stunned into silence” when confronted with the figures.

Andrea Marshall, a contributing author of the study and co-founder of the Marine Megafauna Foundation (MMF), reacted to the new study, saying that watching the decline of manta and devil rays in Mozambique where she works “has been a living nightmare”. “It happened quicker than we could have ever imagined, and it demonstrated to us that we need to take immediate action,” she said.

Three sharks were found to be critically endangered, with their populations declining by over 80 per cent – the Oceanic Whitetip, Scalloped Hammerhead and Great Hammerhead.

Sharks and rays are especially vulnerable to population collapse because they grow slowly and reproduce infrequently.

Overfishing is a clear culprit in their plummeting numbers, and the study notes a major increase over the last half-century in the use of fishing with longlines and seine nets—methods that can snare marine life indiscriminately, including endangered animals.

The analysis was conducted by the Global Shark Trends Project, a collaboration between researchers from SFU, James Cook University, the Georgia Aquarium and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Shark Specialist Group.

The researchers reconstructed the global abundance of oceanic sharks and rays dating back to 1970. There’s no doubting overfishing is responsible for the alarming global decline, according to Nathan Pacoureau, the paper’s lead author who is now an SFU alumnus. Fishing pressure on oceanic sharks and rays has increased 18-fold since 1970.

“We can see the alarming consequences of overfishing in the ocean through the dramatic declines of some of its most iconic inhabitants,” says Pacoureau. “It’s something policy makers can no longer ignore. Countries should work toward new international shark and ray protections, but can start immediately by fulfilling the obligations already agreed internationally.”

—from materials released by Simon Fraser University

Reference

Pacoureau, N., Rigby, C.L., Kyne, P.M. et al. Half a century of global decline in oceanic sharks and rays. Nature 589, 567–571 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-03173-9

Abstract

Overfishing is the primary cause of marine defaunation, yet declines in and increasing extinction risks of individual species are difficult to measure, particularly for the largest predators found in the high seas. Here we calculate two well-established indicators to track progress towards Aichi Biodiversity Targets and Sustainable Development Goals: the Living Planet Index (a measure of changes in abundance aggregated from 57 abundance time-series datasets for 18 oceanic shark and ray species) and the Red List Index (a measure of change in extinction risk calculated for all 31 oceanic species of sharks and rays). We find that, since 1970, the global abundance of oceanic sharks and rays has declined by 71 percent owing to an 18-fold increase in relative fishing pressure. This depletion has increased the global extinction risk to the point at which three-quarters of the species comprising this functionally important assemblage are threatened with extinction. Strict prohibitions and precautionary science-based catch limits are urgently needed to avert population collapse, avoid the disruption of ecological functions and promote species recovery.

.

While I appreciate these types of articles that remind us how bad the state of our ecosystems are, even better yet would be include immediate action steps available to the common person. Perhaps, links to various organizations needing funds to restore ailing coral reefs? Or links to organizations that are cracking down on illegal fishing practices in the Indian Ocean, for example? Or, for those who live on the coast, links to programs and organizations that clean beaches and remove Ocean debris from shallows and reefs.

This type of article is really not that shocking…it is actually surprising there are still that many sharks. What we need is ACTION. The author states “If we don’t do anything, it will be too late.” True, so demand action and others will join you.

As a reefer I have always been a strong proponent of a 1-2$ tax (or a %) on every captive coral purchased with 80%+ of the profits being redistributed into supporting coral reef health and recovery. If you are in the hobby and have had the privilege to observe a majestic ecosystem in your living room, you should be eager to do anything possible to ensure the health and longevity of wild coral reefs, and understand the importance of such a delicate ecosystem.

I am not surprised since, black market for shark fins are very active.China and Japan and many other nations should be forced to stop doing illegal fishing and killing animals just for their own satisfaction. This is so selfish and arrogant.

Thanks for your message, Peca. The issue you bring up is a reality. But, realize that shark deaths are also the result of bycatch. In other words, none selective fishing practices. If you eat marine fish and are not purchasing the product from reputable sources you may be inadvertently funding these unethical fishing practices. So, it’s easy to cast blame on another culture (and I agree that the practice should be stopped), but we all need to reanalyse the decisions we make as consumers since the consumer has the power to implement change if we all ban together.