Helicoprion, a prehistoric shark-like ratfish or chimera, as visualized in a new study. Illustration Credit: Troll & Ramsay.

Scientists have long puzzled over a commonly seen Idaho fossil of shark-like teeth arranged in a circle. Completely unlike anything seen in living fishes and has long posed a conundrum for science. Now a team at the Idaho Museum of Natural History has theorized how the saw-blade like structure might have fit into the jaws of prehistoric ancestors of modern sharks known as chimeras.

Dating to the Paleozoic era, the fossilized circular array of teeth represent a 360-degree biting and tearing tool used by a marine elasmobranch known as Helicoprion, which means “Spiral Saw.” Over the years, many have speculated on how such a lethal organ might worked.

Using CT (Computerized tomography) scans, Dr. Leif Tapanila, head research curator, has offered a new visualization of how the 270-year-old shark-like fish might have looked. (Complete fossils of the soft-bodied animals have not been studied.) The whorl of teeth appears to have acted like a lethal cutting apparatus, enabling the fish to grasp and ingest its prey.

“When the animal closed its mouth on prey, the spiral of sharp teeth rotated backwards, like a circular saw, and slashed through the meat,” says Tapanila.

Coiled teeth of Helicoprion, a Permian shark whose teeth are stored inside its head. Helicoprion teeth are common fossils in the Permian Phosphoria Formation in Idaho. J.R. Simplot Company Collection.

For more than a century, ichthyologists and paleontologists have disagreed on how such an organ might have fit into the anatomy of a living fish, but now the CT scans support its placement in the lower jaw where it was Helicoprion’s complete and fearsome dentition. (It had no teeth in its upper jaw.)

Helicoprion is classified as an archaic ratfish or chimera, described as “the oldest and most enigmatic groups of fishes alive today.” Related to sharks, chimeras have non-bony skeletons of cartilage and are primarily found in deep oceanic waters. Fossilized remains of Helicoprion have been found from the western United States to the Ural Mountains of Russia and China, and it is believed that different species of the genus may have existed.

Further studies of Idaho fossils are planned, says Tapanila, but larger CT scanning equipment is needed for the museum’s biggest and most-complete fossils. He says that Helicoprion might have reached lengths of up to 25 feet (7.6 meters), and the Idaho Museum has one jaw that is two-feet in width, believed to be the largest ever found.

“You know the line from JAWS, ‘You’re going to need a bigger boat’? Well, I need a bigger CT machine,” Tapanila told National Geographic writer Brian Switeck. “I have the world’s largest Helicoprion specimen in the world sitting in my museum, and I see evidence for jaws.”

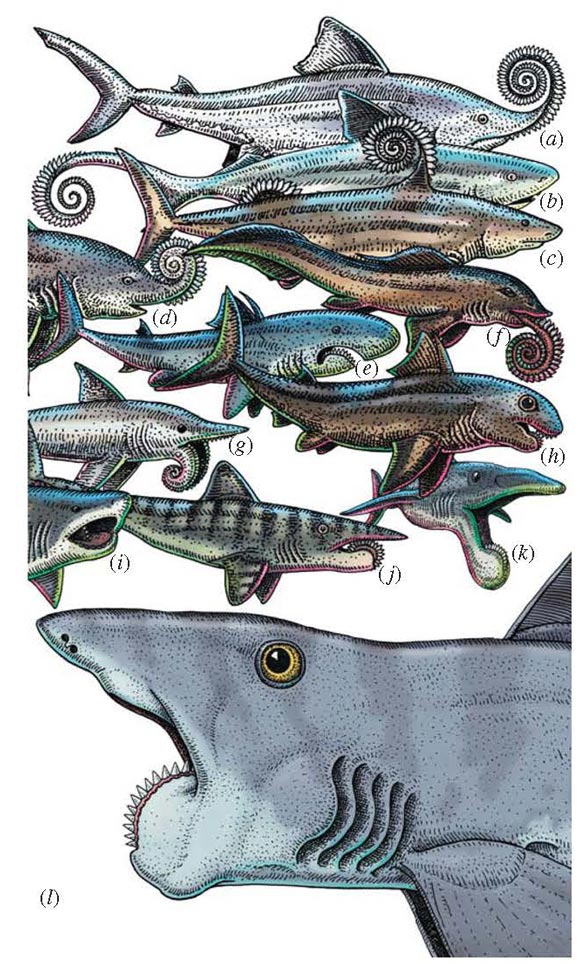

Figure 1. Reconstructions of Helicoprion since 1899. Earliest models (a–d )

posited the whorl as an external defensive structure, but (e–l ) feeding

reconstructions dominate more recent hypotheses. Credits: (a) Woodward

[2]; (b) Simoens [11]; (c) Karpinsky [12]; (d ) Obruchev [7]; (e) Van den

Berg in Obruchev [7]; (f ) John [8]; (g) Carr [9]; (h) Eaton [4]; (i) Parrish

in Purdy [10]; ( j ) Troll in Matsen & Troll [13] based on Bendix-Almgreen

[5]; (k) Lebedev [6]; (l ) Troll & Ramsay, this study. Configuration of gill

slits and fins based on related fish, e.g. Caseodus and Ornithoprion [14].

New CT scans of the spiral-tooth fossil, Helicoprion, resolve a longstanding mystery concerning the form and phylogeny of this ancient cartilaginous fish. We present the first three-dimensional images that show the tooth whorl occupying the entire mandibular arch, and which is supported along the midline of the lower jaw. Several characters of the upper jaw show that it articulated with the neurocranium in two places and that the hyomandibula was not part of the jaw suspension. These features identify Helicoprion as a member of the stem holocephalan group Euchondrocephali. Our reconstruction illustrates novel adaptations, such as lateral cartilage to buttress the tooth whorl, which accommodated the unusual trait of continuous addition and retention of teeth in a predatory chondrichthyan. Helicoprion exemplifies the climax of stem holocephalan diversification and body size in Late Palaeozoic seas, a role dominated today by sharks and rays.

Tapanila, L., Pruitt, J., Pradel, A., Wilga, C., Ramsay, J., Schlader, R., Didier, D. 2013. Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion. Biology Letters. 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0057