Aquarium livestock industry leaders sound positive notes on streamlined detection method

By Ret Talbot

The announcement of a new, non-invasive, non-destructive test for the presence of illegal cyanide in the bag water of collected reef fishes (New Cyanide Test: A Game Changer, Coral Newsletter, April 27), has the epicenter of the marine trade in the United States buzzing. Reaction from 104th Street in Los Angeles, in the shadow of LAX Airport, with a concentration of the world’s largest and busiest aquarium livestock importers has been swift and cautiously optimistic about the new protocol developed by scientists in Portugal.

While some casual aquarists immediately expressed surprise that cyanide use is still as prevalent as it is, those who have been around the trade for any length of time had a more nuanced, mostly positive response. Some of the more interesting observations came from those who have the most proverbial skin in the game–the importers and wholesalers, who, in many ways, are the trade’s gatekeepers.

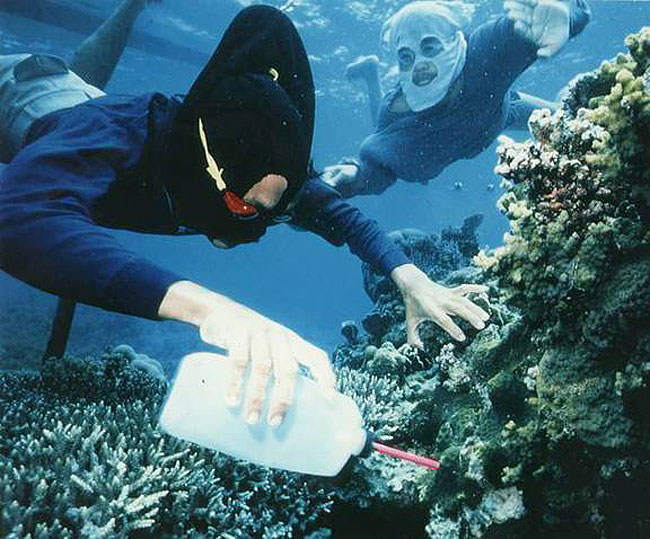

Unlike previously known methods of testing for cyanide, the new method does not require the sacrifice of living fish, nor long, sophisticated, and expensive laboratory work. The researchers say it will offer affordable and almost immediate method for screening water samples from incoming shipments of fish for the presence of thiocyanate (SCN-) a metabolite excreted by fish exposed to sodium or potassium cyanide. Lead researcher in the development of the method was Dr. Ricardo Calado, right, at the University of Santiago, Aviero, Portugal.

Self-Policing Options

“I know what I believe about my sources and what I have been told,” says veteran importer Dave Palmer. “It would be very interesting to see if the test results back that up.” Palmer, below, of Pacific Aqua Farms (PAF), a large Los Angeles-based importer and wholesaler 5450 W. 104th St., says he would support an effective, easy-to-use and cost-effective cyanide detection test. In fact, if the fiber optic sensor described in last week’s article were readily available and affordable, Palmer says he would be interested in using it for in-house verification regarding his sources.

A common theme expressed by most importers was the fact that, in the absence of any cyanide screening, it is difficult to actually know beyond a question of a doubt that the fishes they purchase are collected without employing destructive fishing practices like cyanide. In addition to using the new test to audit his own supply chains, Palmer is curious about other potential uses for the test. “It would be interesting,” Palmer conjectures, “to test the Solomon or Fiji fish when they first arrive and then again after being mixed in the same system with Indonesia and Philippine fish to see if there is any transfer of a positive test from being mixed with other tainted fish.” The crux for Palmer is price. “Lots of interesting things can be done if this test is indeed cheap enough to more or less test at will,” he says.

SDC: Three Strikes Rule Possible

Eric Cohen, below right, of Sea Dwelling Creatures (SDC), 5515 W. 104th St., also expressed enthusiasm for the new test. “This is excellent news,” says Cohen. “We have always pressured our suppliers to provide the best quality possible, but now we can hold them to a standard never before possible.” Like the other importers interviewed for this story, Cohen alluded to the very real challenges of knowing every shipment of animals has been collected without the use of cyanide or other destructive fishing practices.

“With the new test kit for cyanide detection,” he says, “we can now randomly test incoming fish and let our suppliers know that we will not support unsustainable collection methods.” How would SDC implement such a policy? “I believe once we begin the testing stage,” Cohen suggests, “we will implement a three strikes rule and give our suppliers a chance to reform 100 percent or lose the business.”

“Very positive breakthrough…”

Chris Buerner of Quality Marine, 5420 W. 104th St., is as enthusiastic about the new detection protocol as Palmer and Cohen, but he does point out the challenges to importers who do not have tight control and oversight over their own supply chains.

“This is obviously a very positive breakthrough if it is reliable and indicative of responsible collection versus that which is in violation of local fishing regulations,” says Buerner, below left. The challenge, of course, is that if cyanide is detected in fishes at an import facility, that importer could be prosecuted under the Lacey Act even if the importer honestly did not intend to import fishes collected with cyanide. The Lacey Act (16 U.S.C. ¬ß¬ß 3371-3378) protects both plants and wildlife by creating civil and criminal penalties for a wide array of violations, including the trade in wildlife, fish, and plants illegally taken, possessed, transported, or sold.

Every importer interviewed expressed concerns that, given the current state of the trade, it is virtually impossible to know all fishes from all supply chains have been collected legally without cyanide. As several importers pointed out, it is even difficult for all source country exporters to know without question that the fishers from whom they buy fishes have not used cyanide. An easy-to-use, cost-effective testing tool could change that, and it is why such a test is almost universally embraced by most of the major players along the chain of custody for in-house auditing. While most importers readily embrace using the test in-house, whether or not they would as enthusiastically support randomized third-party testing is a more complex question.

“From what I understand current testing methodology is impractical and costly,” says Buerner. “These newer technologies that are being developed will assist regulatory agencies to police industries suspected of using cyanide. Responsible industry operators should be supportive of these efforts which will lend transparency to sustainable collection methods and validate responsible trade, while discouraging those in violation from continuing and misrepresenting animals collected unlawfully.” So are they?

Cross-Contamination Issues

Palmer says PAF would be supportive of third-party testing, but first, he says, he would need to be convinced the test is accurate with no false positives from other sources or from cross-contamination through water or food. “Once I am convinced that the test is accurate,” says Palmer, “I would love to have tests done on incoming shipments before they are put into our system in order to solve any issues that might come up with particular suppliers.”

Like other suppliers interviewed, Palmer says he would be reluctant to allow random testing of fishes in PAF’s system before having a chance to solve any issue that may arise from a particular supplier and be identified through in-house auditing first‚Äìperhaps through a three-strike system such as the one Cohen says SDC would implement.

“The reason for that,” Palmer explains, “is that I would not want to have Solomon fish tainted with a cyanide label if contaminated from a Philippine or Indonesian source. If a third party comes in and starts testing and releases information about the tests before we have had time to solve any issues it could hurt reputations and business severely.”

Palmer points out, as did the other importers interviewed for this story, his suppliers claim to have no cyanide-caught fishes. “But really how can they be sure taking into consideration how fish are collected and the journey they go through in those countries?” asks Palmer. As such, he tells CORAL he would want to test in-house first and attempt to solve any issues before a third party was allowed to test and make the results public. “Too much is at stake when I only have others’ guarantee about the fish I receive,” Palmer concludes. “It would be terrible to bring into question Solomon fish from a cross-contamination.”

Testing Before Exporting

Buerner of Quality Marine says he would prefer source country testing starting at the point of export. This way, he explains, “we as importers aren’t unwittingly importing fishes that have been collected in that manner.” Buerner points out that the longer the supply chain, the more difficult it is to have real transparency. “[It is] no problem on short supply chains where we have good oversight and influence,” he says, ‚Äúbut there are just too many unknowns about the longer supply chains that are, for better or for worse, a central part of the marine aquarium trade at present.”

As many importers expressed in confidence, there is a great deal of concern regarding the politics within the industry when it comes to cyanide. As one importer put it, “there is a lot of posturing done in the industry about suppliers having guaranteed cyanide-free fish, but none of us really know for sure unless we buy only from certain known cyanide-free areas which will limit the species offered for sale. I don’t know of any major wholesaler who does not buy fish from an area that could possibly have an issue with cyanide.”

All importers agreed eliminating cyanide use was an important goal, but most claimed they would have to be assured they would have time to “clean up their own house first” by, hopefully, using the new cyanide detection tool. They also say they would need to better understand the potential for cross-contamination and false positive results.

Palmer agrees wholeheartedly with this assessment. “I think that all the major wholesalers are at risk of having a positive result until they have some time to use the test on incoming shipments and solve any problem that might show up,” he says. “The damage that could be done to someone by releasing test results is great. That is why I think that we all would need some time to use the test and root out any unknown problems that might exist.”

Ret Talbot is a CORAL senior editor reporting on sustainability issues. He is leaving for Indonesia in the coming weeks as part of the Banggai Rescue Project.