CORAL Sr. Editor Michael J. Tuccinardi travels to Kenya and returns with an inside look at East Africa’s Marine Aquarium Trade.

a CORAL Magazine excerpt from the May/June 2017 issue

Part 1 | Part 2

by Michael J. Tuccinardi

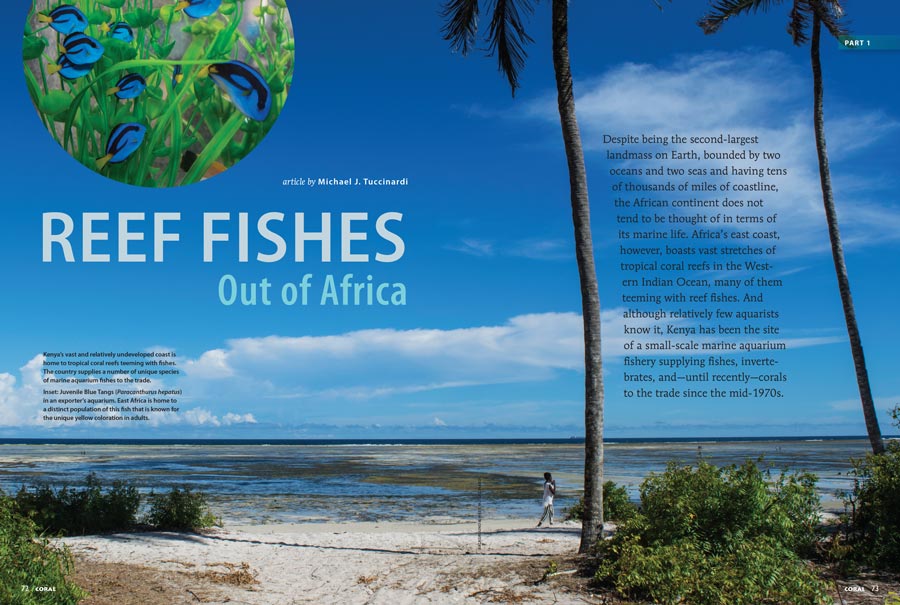

Despite being the second-largest landmass on Earth, bounded by two oceans and two seas and having tens of thousands of miles of coastline, the African continent does not tend to be thought of in terms of its marine life. Africa’s east coast, however, boasts vast stretches of tropical coral reefs in the Western Indian Ocean, many of them teeming with reef fishes. And although relatively few aquarists know it, Kenya has been the site of a small-scale marine aquarium fishery supplying fishes, invertebrates, and—until recently—corals to the trade since the mid-1970s.

Kenyan marine fishes have never been a particularly common sight at American import and wholesale facilities, but in my years at Segrest Farms near Tampa, Florida, I saw a few shipments of fishes and invertebrates from East Africa come and go, piquing my interest in a region that has some truly unique species. In my own travels and explorations of the marine aquarium trade, I’ve always gravitated toward the smaller, more obscure fisheries and collecting regions, and Kenya has remained high on my list of sites to visit. When the opportunity recently arose to not only explore the coastal city of Mombasa—the country’s marine fish export hub—but also to visit collecting sites along the country’s coast with Jochen Federschmied of Kenya Marine Center (a major exporter), I enthusiastically accepted and soon found myself disembarking from a crowded flight into a hot, dusty Kenyan afternoon.

Fish-holding systems at the facility of Kenya Marine Center, a large exporter located just outside the city of Mombasa.

It’s no surprise that Kenya, with just 333 miles (535 km) of coastline, is far better known for its interior, which contains spectacular wildlife habitat and the famed Mount Kilimanjaro, and abuts Lake Victoria, one of the major hotbeds of freshwater cichlid diversity on the planet. Despite that, Kenya’s coast is unique in that much of it is enclosed by a massive barrier reef lying just a few miles offshore. This chain of barrier and fringing reefs extends for over 125 miles (200 km) along Kenya’s shores and southward into Tanzania. The northern Kenyan coast near Lamu has less coral cover due to the out-flowing fresh water of the Tana River, and north of that the coral reef zone is effectively bounded by an upwelling of cool water along the Somali coast, so the Kenyan and Tanzanian coasts comprise a distinct coral reef ecoregion, according to J.E.N. Veron’s online database Corals of the World (www.coralsoftheworld.org). And while the country’s reefs suffered significant bleaching during the highly destructive El Niño Seasonal Oscillation of 1999 (and in subsequent events), overall the fringing and inshore reefs have recovered and survived intact, especially in and around the nearly 10 percent of Kenya’s offshore area that has been set aside as marine protected areas (MPAs).

A group of Allard’s Clownfish (Amphiprion allardi), an East African endemic, in a host anemone on a fringing reef.

Kenya’s offshore habitat is diverse, including nearly every type of tropical marine ecosystem, from vast mangrove swamps, seagrass beds, and shallow Acropora– and Porites-dominated fringing reefs to extensive deepwater fields of soft corals and anemones. Over the course of my five-day visit, I was able to explore most of these habitat types and see many of the fish and invertebrate species that I had previously seen only behind glass. One of the first things that struck me about the underwater scenes off the Kenyan coast was the sheer volume of fishes present—huge shoals of Anthias were almost always in view along the reefs, and there were numerous large predatory fishes, like the schools of massive Southern Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) that I witnessed in the midst of a feeding frenzy just above one of the dive sites. Although it has a history of fishing and coastal resource use that extends back thousands of years, much of Kenya’s coast is sparsely populated, and there is relatively little in the way of industrial or large-scale fishing in most areas. This, coupled with the relatively healthy reefs, means that the fish assemblages along the coast have remained largely intact, despite some localized overfishing of food fish species.

The fish and invertebrate life found on Kenya’s reefs is extremely diverse, and while many of the commonly encountered species are found throughout much of the Indo-Pacific, East Africa boasts plenty of its own endemics. These unique species and distinctive populations— especially of reef fishes—have become staples of Kenya’s export trade, and over the course of my time there I was thoroughly impressed by the stunning array of fishes being collected in this undeniably exotic locale, although few are seen with any regularity in the U.S. aquarium hobby. Despite their relative scarcity in the trade, I couldn’t help but feel that many of them deserve more recognition. From an aquarium enthusiast’s standpoint, they certainly seem worth the extra effort necessary to seek them out—and not just for their uniqueness and suitability for any serious hobbyist who may have grown somewhat bored with the standard species seen in most marine and reef aquariums. I was struck by the obvious vitality and health of these fishes upon import, which was due to careful collecting methods—harmful and destructive techniques, such as cyanide fishing, are not utilized in the Kenyan aquarium trade—and short duration of transit from collection to export station.

For the next issue of CORAL I’ll examine the Kenyan marine fishery and provide a firsthand account of my time spent with the skilled divers who collect these fishes and invertebrates for their livelihoods, but for now I offer a detailed look at some of the country’s most impressive and unique fish exports, along with brief notes on their care in the aquarium.

The beautiful Blue Star Leopard Wrasse (Macropharyngodon bipartitus), a regular export from Kenya, in an exporter’s holding tank.

LABRIDAE

Blue Star Leopard Wrasse (Macropharyngodon bipartitus)

Probably the most beautifully marked of all the leopard wrasses, as members of this genus are commonly called, M. bipartitus is distributed widely throughout the Western Indian Ocean and is extremely abundant on most Kenyan reefs. Although wrasses of this genus have a somewhat deserved reputation for being delicate in the aquarium, much of this is likely due to poor handling and stress during and after collection and importation. A large, well-established aquarium, a substantial sand bed, and ample feedings of varied, high-quality foods appear to be the keys to keeping these somewhat fragile beauties thriving in captivity.

Radiant Wrasse (Halichoeres iridis)

A fish that certainly lives up to its name, the Radiant Wrasse is another Western Indian Ocean fish found in large numbers off the East African coast. Like most of its congeners, it requires a sand bed to sleep in and, while shy at first, generally adopts the gregarious behavior typical for this genus. Some reports indicate challenges with recently imported specimens, which I would probably attribute to transport stress or malnutrition. Most freshly collected fishes are active and enthusiastic eaters.

Yellowtail Tamarin Wrasse (Anampses meleagrides)

Although it is found throughout the tropical Indo-Pacific, this beautifully marked wrasse has long been considered a challenge to keep successfully. Specimens from Kenya, which do not usually suffer from extended time in transit before reaching an exporter, are likely to fare far better in the aquarium, which is why this species remains a popular export from the country.

Yellow-Breasted Wrasse (Anampses twistii)

Like other species of this delicate genus, this wrasse tends to fare poorly when handled roughly or subjected to poor conditions before and during export. Much like the leopard wrasses, they need ample sand beds and large, well-established aquariums to thrive.

Bicolor Cleaner Wrasse (Labroides bicolor)

Without a doubt an experts-only fish, this species should be kept in a large aquarium under the care of a highly experienced aquarist. Carefully collected specimens that haven’t begun wasting away due to lack of food—such as most specimens exported from Kenya—are far more likely to adapt and thrive in an aquarium.

Candycane Wrasse (Hologymnosus doliatus)

This is another commonly encountered denizen of Kenyan reefs. The attractively marked juveniles of this species tend to form loose schools as they hunt for small invertebrates. Relatively hardy in aquariums, they grow to a hefty 12+ inches (30 cm) as adults and so are only suited for large aquariums.

POMACANTHIDAE

Goldtail or Chrysurus Angel (Pomacanthus chrysurus)

This large, attractive angelfish is found only along the east coast of Africa and is among the most sought-after Kenyan exports. Although occasionally encountered on the reef, it tends to be more common in rocky and algae-dominated habitats on the North Coast.

Flameback Pygmy Angel (Centropyge acanthops)

Although remarkably similar to Centropyge aurantonotus, which, oddly enough, is found across the globe in the Southern Caribbean, C. acanthops is endemic to East Africa and sports a more vibrant orange coloration. On the reef, this fish tends to stay close to rock or coral overhangs and makes a colorful, if somewhat shy, aquarium resident.

POMACENTRIDAE

Allard’s Clownfish (Amphiprion allardi)

A beautiful, rather delicate East African species in the A. clarkii complex, A. allardi is typically found inhabiting Carpet Anemones (Stichodactyla sp.) or Ritteri Anemones (Heteractis magnifica). Although it has been bred in captivity, it is not commonly commercially available except as a wild-collected specimen from Kenya.

Vanderbilt’s Chromis (Chromis vanderbilti)

A widespread species that, unfortunately, is rarely seen in the hobby, this small-growing Chromis is both hardy and peaceful. Although not prone to forming tight schools like some of their congeners, they make attractive additions to a reef tank and tend to stick close to branching coral heads.

Juvenile Blue Tangs (Paracanthurus hepatus) in an exporter’s aquarium. East Africa is home to a distinct population of this fish that is known for the unique yellow coloration in adults.

ACANTHURIDAE

Yellow Belly Hippo or Regal Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus)*

*distinct population

Although the Blue, Regal, Palette, or Hippo Tang is among the most well-known and immediately recognizable of all reef fishes, relatively few people are familiar with the fact that there is a distinct population of this fish known from East African waters. These fish, in contrast to the uniform blue they display throughout the rest of their range, sport a pale yellow belly that develops further as they grow. Beyond this unique color pattern, which should interest any aquarium-keeper looking for something out of the ordinary, these fish are typically collected and held under far better conditions than Indonesian specimens, so they tend to acclimate to aquarium life without the health issues that often plague this species.

The bizarre but beautifully patterned Gumdrop Coral Croucher (Caracanthus madagascariensis) is a minuscule relative of the scorpionfishes. Image credit: Mo Devlin / Segrest Farms

SCORPAENIDAE

Gumdrop Coral Croucher (Caracanthus madagascariensis)

This bizarre and minuscule member of the scorpionfish family is extremely similar in behavior to the well-known clown gobies of the genus Gobiodon, inhabiting coral heads almost exclusively in the wild. Technically venomous, these strange little fish adapt relatively well to aquarium life and would make a fascinating centerpiece for a nano reef.

CHAETODONTIDAE

Black Pyramid or Zoster Butterfly (Hemitaurichthys zoster)

This darker, Indian Ocean cousin to the more well-known Yellow Pyramid Butterfly (H. polylepis) is found in large aggregations just offshore along most of the Kenyan coast. This species is generally considered one of the more reef-safe species of butterfly.

Part 1 | Part 2

See More:

See even more images in the lavish full version, published in the May/June 2017 issue of CORAL Magazine. Subscribers can access the digital edition to view this issue in the digital archives, or you can purchase a single-issue copy of the printed magazine through our web store.

Image Credits:

Images by Michael J. Tuccinardi unless otherwise noted.