To some it’s just another blue-green damselfish, but to others, Alelia’s Damselfish is an exciting new marine fish species worthy of some attention from marine fish breeders. Image: Bernadi et al.

Scientists Giacomo Bernardi, Gary C. Longo, and T.E. Angela L. Quiros have recently described a new species of Damselfish, Altrichthys alelia, from Busuanga Island, Philippines. Arguably, this is interesting simply for being a new damselfish species, but the paper’s note that this was a “brooding” species of Damselfish immediately caught my attention.

Did the authors mean to imply that Alelia’s Damselfish has a darkly unhappy personality likely to wreak havoc on an aquarist’s aquarium? While that wouldn’t be all that surprising, in this case “brooding” refers to the reproductive strategy of direct development, where the species’ offspring forego the pelagic larval phase so common in tropical marine fishes, and instead are tended to by their parents until large enough to disperse and fend for themselves.

This was a pretty exciting story for me. As a long-time marine fish breeder I was learning something new. Up until now, the only damselfish species I was aware of that practiced brood care over non-pelagic larvae was the species most commonly sold as the Spiny or Orange-line Chromis, Acanthochromis polyacanthus. This direct-development reproductive strategy is only practiced by a few other tropical marine fish species, perhaps most notably the Banggai Cardinalfish, Pterapogon kauderni, and some seahorse species (Hippocampus spp.). Despite a wide range in the case of A. polycanthus, the lack of a pelagic larval dispersal phase has lead to localized biogeographic variations in genetics, morphology, and even color pattern (sounds like a story familiar to freshwater cichlid keepers).

What’s alluring to marine fish breeders about direct-development is that it represents a reproductive strategy that the aquarist is likely already well-versed in from freshwater experiences: working with A. polyacanthus is potentially not unlike working with Discus (Symphysodon spp.), while working with the mouthbrooding Banggai Cardinalfish has always reminded me of my experiences breeding Frontosa (Cyphotilapia spp.). A prospective breeder might only have to have experience hatching brine shrimp (Artemia nauplii) as a first food. Success, hypothetically, should come swiftly and easily. So why don’t we see a plethora of captive-bred Spiny Chromis everywhere?

Adult Spiny Chromis, Ananthochromis polyacanthus, photographed in Nick Krumrie’s tank several years back. They have a very pleasing shape, but perhaps leave something to be desired in the coloration department. Image: Matt Pedersen

Well, on the most basic level, there are two reasons. First, wild-caught Spiny Chromis are dirt cheap: online retailers sell the juveniles for less than $5 per fish. So, odds are good that there’s no real monetary incentive to breed this species. But perhaps more importantly, Spiny Chromis are one of those marine fish species that I have to wonder if we should even be keeping. Now, to give credit where it’s due, no freshwater aquarist that likes big cichlids would balk at the fundamentally graceful shape of an adult Spiny Chromis. But at 5 inches (13 cm) or more, and simply sooty black in most cases, this is not a damselfish that people are going to be clamoring over; there are simply more attractive, less belligerent choices for the average marine aquarium. So while a breeder might be inclined to try this species simply to add an accomplishment to his or her list, I just don’t see real long-term viability for this species in culture at this time.

Attractive Newcomer

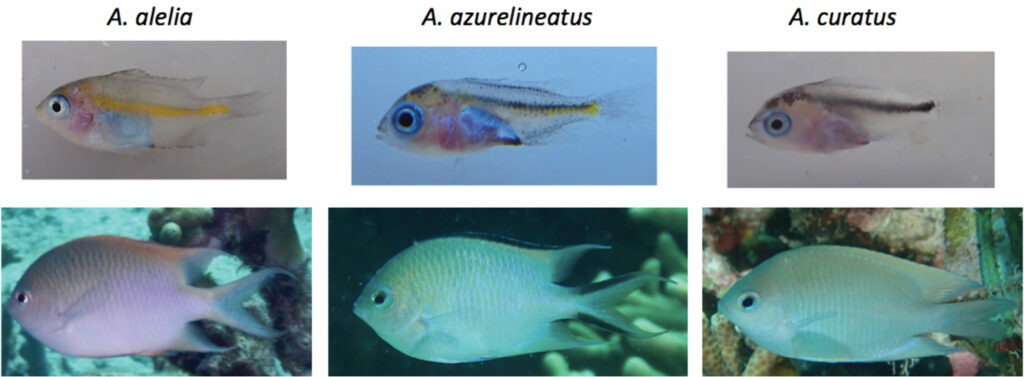

But that’s where the newly-described Altrichthys alelia and its relatives come in. A. alelia is apparently neither large (the largest adult from the description was just over 2″ in length), nor is it unattractive. In fact, on the surface, the photos presented show a very pleasing coloration similar to that of the popular Green Chromis, Chromis viridis. Plus, the closely related A. azurelineatus, also found in the Philippines, is even more attractive (to my taste), sporting a black dorsal margin and black edges on the top and bottom of the deeply-forked caudal fin. And the implication from the authors is that yet another species, A. curatus, is also a brooder, making all three species in the genus of particular interest. Looking at the photos provided, A. alelia sports a downright vivid yellow stripe as a juvenile, which might be a big selling point for a captive-bred damselfish.

All three species of Altrichthys are attractive as adults, suggesting some promise as aquaculture candidates. Image: Bernardi et al.

This now has me on the hunt. This publication has opened my eyes to a few damselfish species that have the potential to be an “easy” species first, and these actually look like species that could sell. I’ve never kept any damsels from the genus Altrichthys, however, never mind that I’ve never seen one before this week, so whether they actually make good community tankmates or not is difficult to say. If any of these brooding damselfishes find their way into your tanks at some point in the future, remember that—just like your average cichlid or clownfish pair—you can hardly blame them if they become aggressive when they start breeding; they’re doing what they’re biologically programmed to do!

Consider this a shout-out and blanket request: I am ready to stake a claim. If you happen to come across a group of A. azurelineatus, shoot me an email. I’ll let some other breeders chase A. curatus and the new A. alelia; there are enough species to go around!

Be sure to read the full species description in the open access paper published in Zookeys.

References:

Bernardi G, Longo GC, Quiros TEAL (2017) Altrichthys alelia, a new brooding damselfish (Teleostei, Perciformes, Pomacentridae) from Busuanga Island, Philippines. ZooKeys 675: 45-55. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.675.12061

Kvanagh, Kathryn D. (2000) Larval brooding in the marine damselfish Acanthochromis polyacanthus (Pomacentridae) is correlated with highly divergent morphology, ontogeny and live-history traits. BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 66(2): 321–337.