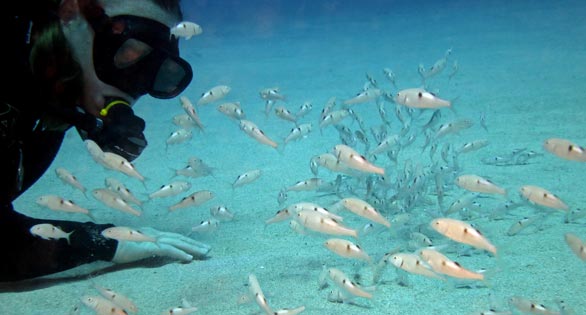

Swarms of butterflyfishes, tangs, and other reef fishes appeared throughout Hawaii. Image: Pauline Fiene.

Widespread reports of an unprecedented recruitment of reef fish juveniles in the Hawaiian Islands

By Ret Talbot

“My eyes feel full when looking at this many fish,” says Pauline Fiene, a veteran diving guide with Maui-based Mike Severns Diving. “[My eyes] almost itch; it’s so overwhelming.” In what she and others have termed a “once in a lifetime” event, “swarms” of small fishes appeared in unprecedented numbers throughout the Hawaiian Islands this past summer.

One local media story even referred to the event as “biblical,” and while the published, peer-reviewed data are still lacking, there is little doubt that something very unusual did indeed happen. Juvenile reef fishes have appeared in numbers never before seen by the current generation of divers in the Hawaiian Islands. Especially noteworthy are swarms of butterflyfishes, surgeonfishes and tangs, goatfishes, snapper, gurnards and other near-shore fishes—some of interest to aquarists, others as part of Hawaii’s food fishery and some of no real fisheries value at all. As one aquarium fisherman put it, “It’s somewhat satisfying that this recruitment pulse is occurring right when some of the activist groups are loudly proclaiming that Hawaii has no fish left. Clearly this is not the case!”

Many reef fishes are pelagic spawners, meaning the parents release their gametes into ocean currents, where external fertilization occurs. Because the fertilized eggs and larvae are relatively buoyant, they are susceptible to prevailing ocean currents, eddies and other oceanographic and meteorological conditions that carry them during what can be an extended planktonic larval phase. The iconic Yellow Tang (Zebrasoma flavescens), for example, spends approximately two months of its life cycle drifting in open water before finally homing in on a site where it will attempt to settle. While pelagic spawning has some evolutionary advantages, especially when it comes to a species’ ability to disperse itself far and wide, it is also a reproductive strategy that usually results in huge mortality. Relatively few young fishes that develop properly during the larval phase and manage to avoid predation actually succeed in locating a reef suitable for settlement, hence the massive numbers of eggs often produced by pelagic spawners.

Those very young fishes that do settle successfully onto a reef are frequently referred to as “recruits,” and the mechanism by which they arrive at the reef is called “recruitment.” Recruits show up on reefs downstream of their parents—it’s been shown that Yellow Tang recruits can travel at least 184 km (115 miles) from their parents—in a fairly predictable cycle of so-called “drops.” In Hawaii, there are, generally speaking, two drops of recruits, with the summer drop that occurs from June through August being the larger of the two for most species. While the cycle itself is fairly predictable, the number of recruits is highly variable from year-to-year, and this can have a significant effect on the abundance, density and distribution of adult fish populations. As such, understanding the mechanisms and effects of reef fish recruitment is critical to effectively managing ecosystems for both conservation and fisheries.

What remains unclear, however, is what this summer’s huge numbers of young fishes says about the health of Hawaii’s reefs and both the short- and long-term sustainability of its fisheries, especially the highly controversial aquarium fishery.

Unusual Recruiting Patterns and Smiling Fishers

As Matthew Ross, an Oahu-based aquarium fisherman, explains it, “Recruitment, known colloquially among fishermen as ‘the drop’ is basically what defines our fishing season.” Ross likens it to how a farmer’s season depends on the rainfall and weather. “Every year is different,” he says, “usually some fish are plentiful and some aren’t. Occasionally we’ll get a year where most fish are abundant, and, unfortunately, we sometimes get years where practically everything is scarce…. Personally, watching the drop is one of the things I enjoy most about being in the fishery; it’s always exciting to see what pattern will emerge each year.”

“The recruitment has been strange this year,” says aquarium fisherman Tony Nahacky, who lives on the Big Island of Hawaii and has been diving the reefs since the late 1960s. West Hawaii, called the Kona Coast, where Nahacky has been diving for years, is where most of the fishing for aquarium species occurs in the State. The number of aquarium fishermen operating on the reefs of West Hawaii is relatively small compared to other fisheries, but they are closely attuned to the natural cycles. “Each year the aquarium fishermen eagerly anticipate the annual recruitment to see if it is going to be boom, average, or bust,” says Nahacky.

“This year we are smiling.”

Yellow Tang juveniles: the Biggest “Drop” of a lifetime for many reef observers. Image: Dr. William Walsh/DAR

In addition to observing much larger than normal numbers of recruits of several species of fishes on the reefs where he usually dives, Nahacky says he’s also noticed some other recruitment anomalies. For one thing, he has observed that a number of species appear to be recruiting at unusual times. “For example,” he says, “Hemitaurichthys polylepis [Pyramid Butterflyfish] I usually see arriving in September or October, but they were arriving by the end of June this year.” In addition, Nahacky says he has seen species that usually do not recruit on West Hawaii reefs recruiting in large numbers compared to normal. “Heniochus diphreutes [Pennant Butterflyfish], which recruit on Oahu,” he says, “are quite rare to see as juveniles here, but there were groups up to 70 we spotted.”

“Essentially,” Nahacky concludes, “you have a mix of unusual recruiting patterns this year. This is, of course, anecdotal information based on my observations and memory of past recruitment, but in discussion with other long time collectors they agree.”

Scientists Say It’s “Off the Chart”

Dr. Brian Tissot is the Director of the Marine Laboratory at Humboldt State University, and he, along with other scientists, has intensively studied the reefs of West Hawaii since 1999. “A typical year for Yellow Tangs,” says Tissot, “may show three to seven recruits per 100-square meters (about a thousand square feet) during the summer, with 10-15 per 100-square meters during good years.”

“This year the numbers were off the chart,” says Tissot, who was not been in Hawaii himself this summer but who has graduate students from his lab reporting back to him. “I don’t know the actual numbers,” he says, “but they were an order of magnitude higher at least and perhaps more.” Tissot says it is very unusual to see hundreds of recruits in a small area, but that’s exactly what people were seeing and documenting in Hawaii this summer.

Dr. William Walsh, an aquatic biologist with the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), has been on the reefs this summer, and while he is unable to share actual survey numbers at this time, he confirms what everyone else is saying.

Walsh has been conducting reef surveys on West Hawaii reefs since the 1970s, and what he has observed this year is, in some places, nothing short of what he terms “Amazing.” At one of his survey sites, for example, Walsh says he documented “unprecedented recruitment of Yellow Tang and Lavender Tang” (Acanthurus nigrofuscus). He also reports very good numbers of some butterflyfishes and other surgeonfishes at the site. Other survey sites saw very good recruitment of some species like the Klein’s Butterflyfish (Chaetodon kleinii), various goatfishes, trumpetfish, Heniochus Butterflyfish, Chevron Tang (Ctenochaetus hawaiiensis), Multiband Butterflyfish (Chaetodon multicinctus), and Kole Tang (Ctenochaetus strigosus).

Walsh cautions that not all of his survey sites have seen exceptional levels of recruitment. “Our other sites have varying levels of recruits,” he says, “but really nothing too amazing. Good but not incredible.” Still, what he has seen this summer, he says, is unprecedented in his 40 years of conducting reef fish surveys in West Hawaii.

A Happy Synchronicity?

Neither Walsh nor Tissot know why this summer’s drops of many reef fishes throughout Hawaii have been as remarkable as they have been. “I don’t have an answer as to why such boom recruitment years occur other than they do,” says Walsh. There have been other good years for individual species, and there have even been some truly remarkable years, but they are often species-specific. Among the possible factors are water current patterns, weather, temperature, availability of foods, reduced predation and others.

“I don’t know why this occurred,” says Tissot. “I’m not sure anyone does. It may just be a happy synchronicity between multiple factors that influence larval success,” he conjectures, “or just a rare spawning event involving many species triggered by some environmental cue.”

“I’m sure there is all kinds of speculation on the causes,” Ross says, summing up the fisher perspective. “We all have our own crackpot theories. Some guys think it’s correlated to the prevailing winds, and some think the winter surf has something to do with it. I’m sure that folks in the conservation world are attributing it to the [Fishery Replenishment Areas] or some other conservation measures that have been enacted recently.” Ross’ own theory is that there is better fish recruitment when the water warms up faster in the summer. “But like I said,” he cautions, “this is a crackpot theory and who knows if it’s true or not.”

While he’s not sure of the causes, Ross is convinced it has nothing to do with fishing. “Since the high recruitment seems to be arbitrarily encompassing species that are caught for aquariums, caught for food, and not caught by anyone, I don’t think fishing has anything to do with it,” he says. “The ocean is so complex that I imagine it will always be a mystery.”

Regardless of why this year’s recruitment was so good, many people are asking what it means about the current and future health of Hawaii’s coral reefs and the fisheries that depend on them. Dr. Bruce Carlson is the former director of the Waikiki Aquarium on Oahu, science officer at the Georgia Aquarium, and member of the Senior advisory Board of Coral Magazine. An avid SCUBA diver, Carlson has logged plenty of time on Hawaii’s reefs. He recalls the massive recruitment of Fantail Filefish (Pervagor spilosoma) in the late 1970s and again in the late 1980s, and another influx of Hawaiian Bigeyes (Priacanthus meeki) in 2002. He adds that these events are retold in some Hawaiian legends so they are not just a modern phenomenon.

Carlson says these occurrences dramatically illustrate the dynamic nature of reef fish populations, and that random events may cause much of the variation in recruitment from year to year. “Most of these little fish will probably end up as food for larger fish like ulua [“ulua” is a generic Hawaiian name for jacks, such as Caranx melampygus].” Nonetheless, he says, this year’s event suggests to him something about the health of Hawaii’s reefs in general. “It’s not bad for a reef system that has, as some would have us believe, been decimated by tropical fish collectors,” says Carlson.

Anti-aquarium fishery activists, now bolstered by the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, have been fighting for years to shut down what they say is an unsustainable fishery. Both the State of Hawaii and the preponderance of peer-reviewed scientific literature claim the fishery is amongst the best managed in Hawaii and is sustainable.

From a fishing perspective, Ross is optimistic. “As far as the effects on the [aquarium] industry go, it’s definitely reassuring to see so many fish on the reef,” he says. “Over the years, the fish stocks here have been very good, and I’ve never felt that fish overall were in short supply. This year, however, there is so much that next year could have terrible recruitment and we’d still be okay.” Ross says fishers are also pleased to see some of the less common species, like Thompson’s Tangs and Pyramid Butterflies, be so abundant. “They are good aquarium fish,” Ross says. “It’s good to know that we’ll be able to provide them to the hobby on a consistent basis this year.”

A Regional Phenomenon?

While much of the discussion regarding this year’s recruitment has been centered on Maui and West Hawaii, Ross reports it is the best recruitment year he has ever seen in 12 years diving Oahu. Oahu’s aquarium fishery is tiny compared to that of West Hawaii, but it is a fishery that relies heavily on diversity as opposed to West Hawaii which relies overwhelmingly on Yellow Tang. “We’ve had huge pulses in the past,” he says, “but those usually have been limited to one species at a time. This is different. Most species of fish are very plentiful, with a few types in particular so abundant that they’re forming huge schools that clearly exceed the carrying capacity of the reef and aren’t displaying normal behavior.”

Dennis Yamaguchi, one of Hawaii’s most-experienced aquarium fishermen with more than 40 years of Hawaii diving experience, says last year’s Yellow Tang drop on Oahu was the best he had seen since the 1970s. “This year,” he says, “is light years beyond that.”

As in West Hawaii, the Oahu aquarium fishers and other divers are reporting exceptional drops of both surgeonfishes and butterflyfishes. “Practically all of the tangs, especially Yellow Tangs, Naso lituratus, Kole, and Thompson’s Tangs (Acanthurus thompsoni), are everywhere,” says Ross. “They are so abundant that all of these species are occurring in large numbers outside their usual habitat.” Ross explains that Yellow Tangs are usually found chiefly in finger coral, antler coral trees, and occasionally in rubble around Oahu, but this year, he says, there are large numbers of them “pretty much anywhere with any kind of structure.”

When it comes to butterflyfishes, Ross says Pennant Butterflyfish (Heniochus diphreutes) are especially noticeable, as are Pyramids (Hemitaurichthys polylepis) and Longnose Butterflyfish (Forcipiger flavissimus). “Probably the most abundant one, though, is the Klein’s Butterfly,” he says. “They are so abundant on the North Shore right now that, in some places, they are forming a layer six-foot [two meters] deep that’s hard to see through.”

One of Ross’s most-interesting observations is not one he made while diving though. As part of Oahu’s extremely small aquarium fishery, Ross is, almost by necessity, familiar with all aspects of the fishery from harvest to import and export. “One thing we’ve noticed,” he says, “is that Christmas Island has been shipping huge numbers of Chevron Tangs and Black Tangs—much more than normal.” Perhaps, Ross conjectures, this recruitment event might not be limited to Hawaii.

Long-Term Effects?

Like Carlson suggests, many observers believe a large number of the recent recruits will still succumb—or already have succumbed—to predation or lose out to competition. “These fish appeared to over-populate the reef and are being quickly consumed by predators,” says Nahacky. “Within 30 days, the recruitment looked like a good year but not like it had when the fish first appeared. If you were not diving during the 30-day period this occurred, you would never even know it happened.”

Tissot says his graduate students observed a similar pattern. “Most of the recruits were gone after three to four weeks,” he says. “Probably through mortality, but I have heard that the high abundances caused competition and habitat displacement of some species, which led to mortality.” Tissot cites a specific example with juvenile Yellow Tang, which are frequently targeted in the aquarium fishery and are normally common at nine to 16 meters (30 to 50 feet). “This year they were displaced into shallow water by all the recruits and did not do all that well, as it is poor habitat with not much refuge space.”

Never-before-seen numbers of Klein’s Butterflyfish, Chaetodon kleinii, are being reported. Image: Karen Williams Bryan.

Walsh says he is following up on the question of post-settlement mortality in subsequent surveys, but he points out that developmental behavior must also be taken into account.

“One thing to note about predation,” he says, “is that it seems that for non-schooling species such as Yellow Tang—at least as juveniles—their clumped settlement pattern changes in the weeks post-settlement as intra-specific agonism sets in and individuals become more spaced out and oriented to the bottom.” Agonism refers to behaviors such as aggression, defense and avoidance, and such behaviors, Walsh says, can drastically change the way these fishes present to divers on a reef.

For some of the species that rarely recruit on West Hawaii reefs, an unusually good recruitment year could be an important mechanism to help sustain populations over years of low to no recruitment. “Some of the species that are heavily recruiting this year,” says Tissot, “are seen very rarely as new recruits.” He cites Klein’s and Pennant Butterflyfishes, as well as Blue-lined Snapper (Lutjanus kasmira). Walsh agrees about the importance of recruitment events like this one especially on species that recruit rarely. For example, Walsh observed the first few Fantail Filefish (Pervagor spilosoma) recruits in decades. “Just a few,” he says, “but we haven’t recorded any at all in the previous 15 years in West Hawaii.”

Over on Oahu, Ross says some of the usually rare species are unusually common this year. “We’ve been seeing juvenile Tinker’s Butterflies [Chaetodon tinkeri] consistently on some of our deeper dives; usually they are very rare on Oahu except in very deep water and one small area in the Windward side that’s hard to access. I was fortunate enough to collect a Holanthias fuscipinnus [the very rare Yellow Anthias] earlier this month in only 120′ of water,” he adds excitedly. “Usually they are found only in 400 feet and rarely at 300 feet.” Ross also says small bandit angelfish (Apolemichthys arcuatus) are more common than usual this year.

Putting It All in Perspective

Echoing Carlson’s comments, Nahacky tries to keep it all in perspective. “The large recruitment this season on many species of fish, while exciting, is part of the regular ‘boom and bust’ variation that takes place on the reefs.” Nahacky, like Carlson, believes the better-than-average recruitment suggests there is sufficient broodstock to provide replenishment of the West Hawaii reefs for a sustainable aquarium fishery and a healthy ecosystem.

In addition, Nahacky points out, new fisheries management and conservation measures will likely bolster an excellent recruitment year like this one. These measures include a 40-species White List of fishes permitted for harvest, size and bag limits for several species, and an extensive network of so-called fishery replenishment areas, where no aquarium fishing is permitted. These measures only apply to the West Hawaii aquarium fishery and do not apply to any other fishery in the State such as the Oahu fishery.

“Some species that normally recruit in small numbers,” says Nahacky, specifically citing the Teardrop Butterflyfish (Chaetodon unimaculatus), “have recruited in much greater than average numbers this year. As some of these species are now part of the biodiversity protection provided by the White List, it will be interesting to see if this recruitment changes the current population levels or not over the long term.”

As incredible as this event has been to anyone who had the good fortune to observe it first hand, its true effects will only be known with some hindsight. There is a general consensus in the scientific community that fishery and conservation management efforts in West Hawaii are improving both the community structure of reef systems and the aquarium fishery itself. Perhaps somewhat ironically, it is largely because of how controversial the aquarium fishery has been over decades in Hawaii that scientists and fisheries managers have the data that demonstrates sustainability and provides much of the foundation for insuring future sustainability through even better management. If not for this controversy over the aquarium fishery, the years of data that will eventually contextualize this would likely not exist, and both conservationists and fisheries scientists would most certainly have lost an invaluable opportunity to learn from this remarkable event.

Source: Excerpted from an article that will appear in the November/December 2014 issue of CORAL Magazine.

About the author: Ret Talbot is a Senior Editor of CORAL Magazine and a photojournalist who covers fishery issues. He is the lead author of Banggai Cardinalfish (2013) and he lives in Rockland, Maine.

Has there been any correlation with recruitment and typhoons? Is there any research that shows typhoons impact the feeding patterns of offshore pelagic feeders that might reduce the larval predation?