Adult Pygmy Seahorse, Hippocampus bargibati, on pink coral, Muricella – it was unknown if they would venture onto the pink coral. Image by Richard Ross

Opinion by Matt Pedersen

We just shared the news of the first successful captive-breeding of Hippocampus bargibanti at the wet hands of Steinhart aquarists Matt Wandell and Richard Ross. Marine breeders, and more specifically seahorse propagators, are no doubt ecstatic (Dare I borrow a line from from Ross: “Their heads are falling off”).

Of course, why didn’t this happen until now, and why can’t we all rush out to buy a captive-bred Bargibant’s Seahorse?

An article by Nick Stockton released June 17th, 2014, via Wired Magazine gives a glimpse into the planning and permitting necessary to undertake this project. Truthfully, this accomplishment could have only occurred under institutional auspices; according to Stockton’s article: “The Steinhart team had to get permits not only from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), but the Philippine government and the local mayor before they could ship their cargo home.”

Four-Inch Limit

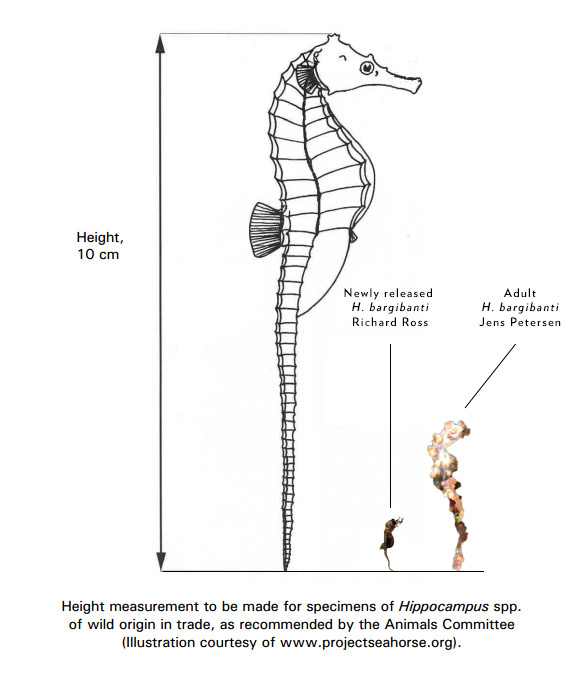

Seahorses (Hippocampus spp.) have been CITES listed since 2002, with their trade regulated since May 15th, 2004; they currently fall under Appendix II. International Trade restrictions limit the size of traded seahorses to a minimum length of 10 cm (commonly converted and rounded to 4 inches in the US).

A graph of seahorse species in relation to their size at maturity and maximum size, as prepared by the Sygnathid working group for CITES in August of 2002.

The goal of this limitation is was to, “identify a minimum size limit for specimens of all Hippocampus species in trade as one component of an adaptive management plan, and as a simple precautionary means of making initial non-detriment findings in accordance with Article IV of the Convention.”

In short, the working group was asked for an easy metric by which the trade in the genus Hippocampus might be permissible and non-detrimental to wild populations. As visually demonstrated in the graph above, this limitation was enacted knowing that it would effectively eliminate the trade in approximately 11 known species of seahorses at the time. They excused this limitation with the explanation that, “[the] very limited trade in the 11 small species is currently derived from captive-breeding facilities or largely domestic.” To date, this size restriction is voluntary, that is it is not mandated, but governments (like the US) adhere to it. Furthermore, the limitation is specifically set for wild-caught, wild collected Seahorses; CITES has not enacted or recommended any size restriction on captive-bred animals.

You can freely and easily find the Dwarf Seahorse, Hippocampus zosterae, as a wild-caught fish in US aquariums and retail shops, quite inexpensively. It definitely comes in at under 4 inches in maximum length; Fishbase cites the max length as 5 cm (roughly 2 inches). The Dwarf Seahorse is native to our waters, and thus our domestic trade in the species is not governed by CITES rules (which cover international trade alone). However, the CITES rules come into play the moment we try to export the fish. It’s not permitted to be traded as a wild caught animal due to the adherence to voluntary minimum size guidelines, so aquarists in every other part of the world have great difficulty obtaining and keeping our Floridian Dwarf Seahorse, having to rely squarely on captive-produced animals.

Trade Hurdles

Of course, the hurdles are many when it comes to doing something as simple as getting a captive-bred H. zosterae from the US to another country, the burden starting with simply proving that the animal was captive-bred in the first place, and then getting both the US government and the government of the destination country to agree that the transaction can happen.

I’ve personally been caught in the middle of such a quandary in the orchid business, in that case attempting to import a rare orchid species from Japan. In my situation, the process ultimately stalled with the US saying they would grant the import permits if Japan granted the export permits. Meanwhile, Japan’s government said they would grant the export permits if the US granted the import permits. Ultimately, no one granted any permits, but I was out several hundred dollars in permit application fees and not a dime was ever refunded.

Under current national and international regulations and the voluntary minimum size rules, there is no likely way for the general aquarium trade to legally export wild-caught Seahorse species under 4-inches in length from their source country, effectively preventing offsite commercial and private breeders from obtaining the broodstock necessary to start captive propagation of a species like Hippocampus bargibanti. Even though this size rule is voluntary, I suspect any attempts to export wild seahorses under the size recommendations would wind up in a similar stalemate as described above, even in the best case scenario, unless you happen to qualify for research and scientific exemptions (as Steinhart would have).

Therefore, the only way for a species like H. bargibanti to realistically legally enter the international aquarium trade would be through a captive-breeding effort in the source country (eg. someone breeding this species in the Philippines), and government verified and sanctioned exports of the species to countries abroad, providing that destination countries are willing to believe the endorsements of the exporting country.

CITES documentation showing proper measuring of a Seahorse – we’ve augmented it here to show, in relative scale, both the newborn and adult Hippocampus bargibanti (newborn image courtesy Richard Ross, adult image from wild by Jens Petersen)

Such a process is not unique to Seahorses; new orchid species of CITES restricted genera can only make their way into the commercial orchid trade through similar methodologies—they must be cultured in their home country and can then be exported under exemptions that allow for the trade of captive-produced plants. For the record, it is far easier to prove that an orchid is “captive-bred” (they must be sown in sterile lab conditions and grown on agar in an almost completely sealed flask…no way to fake it), vs. a 1-inch long seahorse. It would be much easier for someone to set up a “propagation facility” in an island nation and then launder wild-caught fish through it. And thus, why Appendix I orchids are readily available in commercial interantional trade, while the same cannot be said for a fish like Hippocampus bargibanti.

Wandell and Ross’ successful breeding efforts are only possible due to the institutional exceptions granted for scientific research and other sanctioned academic pursuits. Private aquarists should not get their hopes up that we’ll see captive-bred Bargibanti Seahorses in the aquarium trade anytime soon.

The Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) guidelines basically encourage a practice of distributing surplus animals propagated at AZA-sanctioned facilities to other AZA facilities, other researchers, academics and such. You’ll only find the aquarium trade, and private aquarists, at the very bottom of that list of unwritten preference. The aquarium trade is even expressly called out in the AZA guidelines with the following recommendations:

via AZA – Fish and aquatic invertebrate species that meet ANY of the following are inappropriate to be disposed of to private individuals or the pet trade:

- species that grow too large to be housed in a 72-inch long, 180 gallon aquarium (the largest tank commonly sold in retail stores)

- species that require extraordinary life support equipment to maintain an appropriate captive environment (e.g., cold water fish and invertebrates)

- species deemed invasive (e.g., snakeheads)

- species capable of inflicting a serious bite or venomous sting (e.g., piranha, lionfish, blue-ringed octopus)

- species of wildlife conservation concern

It is fair to say that H. bargibanti could easily fail the test when considered against the 2nd and 5th subjective guidelines; this further increases the likelihood that aquarists and the aquarium trade will be a last-resort recipient.

Similarly, the Lake Victoria Species Survival Program (LVSSP) utilizes a similar guideline for participating institutions to dispense of excess animals from the SSP. Only if efforts to place the surplus animals with AZA-accredited institutions have failed, may these animals be sold, traded, or given to private individuals and/or the aquarium trade.

In other words, only if the public aquarium world becomes so flooded with Hippocampus bargibanti that no one wants them, do we realistically stand a chance at seeing Hippocampus bargibanti released to the general public. This, of course, presumes that the permits, permissions, and agreements obtained by Steinhart would even allow for that to happen.

For now, it is best to start thinking about a trip to the Steinhart Aquarium at the California Academy of Sciences, which will obviously become one of the first (if not the first) aquariums in the world to put the tiny, stunning, adorable, Bargibant’s Seahorse on display. While it’s possible we may someday see commercially available, captive-bred H. bargibanti, it’s probably years away at the earliest.

Images Credits:

Opening Image of H. bargibanti courtesy Richard Ross

CITES Graph – http://www.cites.org/eng/com/ac/20/E20-17.pdf

CITES Seahorse Measuring – http://www.cites.org/eng/notif/2005/014.pdf

Juvenile H. bargibanti courtesy Richard Ross

Adult H. bargibanti by Jens Petersen, Creative Commons License

Trackbacks/Pingbacks