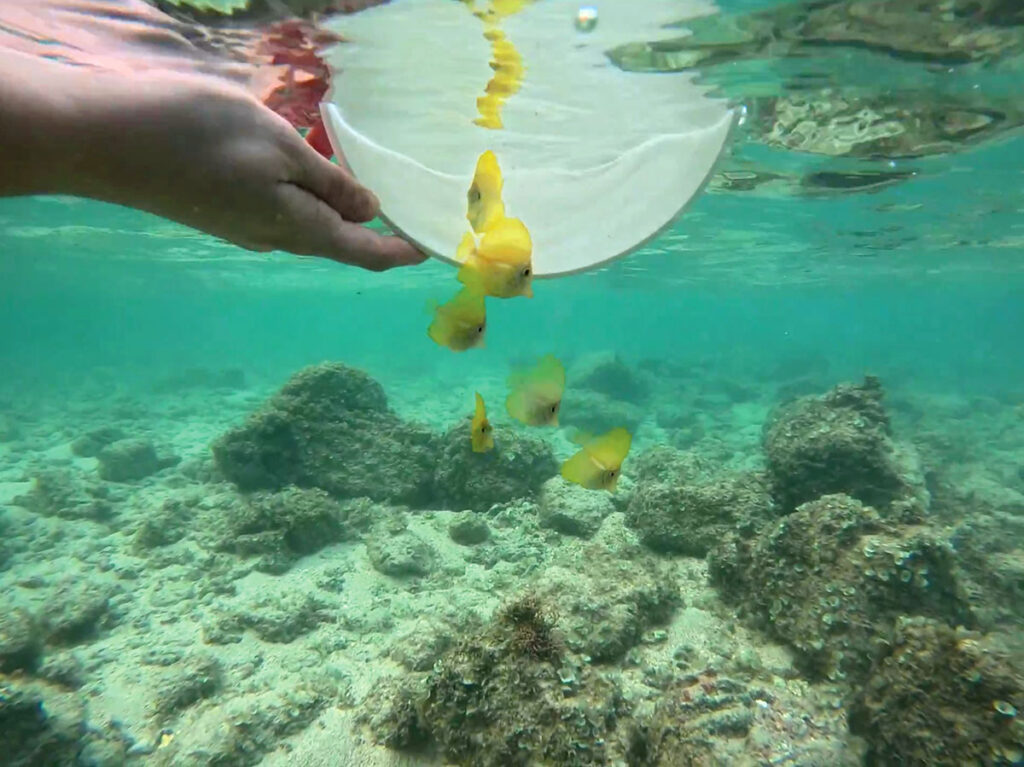

INTERVIEW | CORAL staff interviews CHAD CALLAN, KATIE HIEW, & SPENCER DAVIS

A special full excerpt from the January/February 2025 issue of CORAL Magazine.

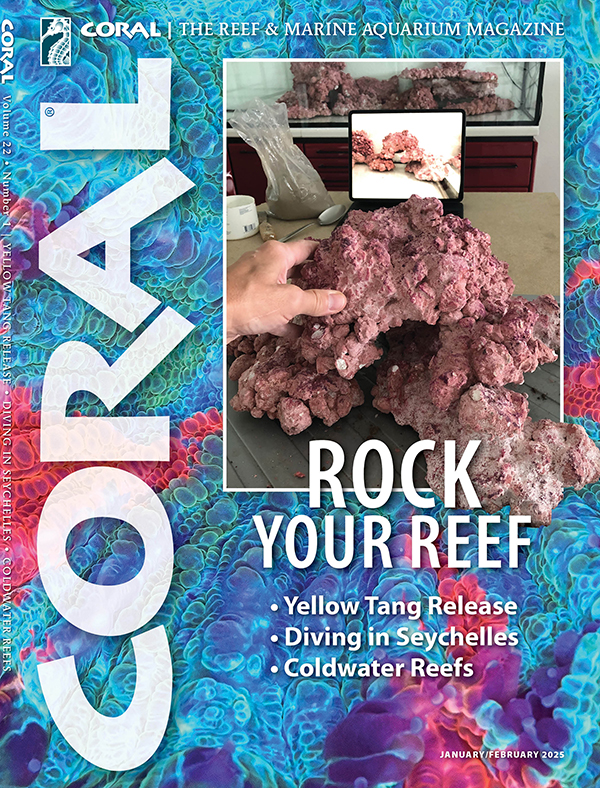

News of the early November release of over 300 aquacultured Yellow Tangs (Zebrasoma flavescens) into Hawaiian waters by researchers at the Oceanic Institute of Hawaii Pacific University (OI) located in Waimanalo on the east side of the island of Oahu, Hawaii, sparked an unprecedented reaction from aquarists on the Internet. Responses ranged from outrage to cheering support. The public comments and questions illustrated that there was significantly more to learn about what was done by the team at the OI, and why. Perhaps most important in this follow-up is to start the discussion by framing things clearly; what the world saw was just a moment in time, and the proverbial “tip of the iceberg”. What some called a PR stunt is viewed by others as a proof of concept.

Regardless of how you interpret what was accomplished, this was a day where the worlds of marine ornamental aquaculture and reef restoration evolved—not in some massive, Earth-shattering explosion, but rather through a small symbolic act that wasn’t possible before. In an effort to learn more about this Yellow Tang release, CORAL Magazine Editors Marc Levenson and Matt Pedersen spoke with Chatham (Chad) Callan (Associate Professor of Aquaculture at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, and the Transition Advisor/Director of the Finfish Program and Affiliate Faculty at OI), Katie Hiew (Finfish Program Research Associate) and Spencer Davis (Finfish Program Senior Research Associate). We sought additional viewpoints from outside of the OI program, including attempts to connect with Hawaii’s DAR (Division of Aquatic Resources), but did not receive comment in time for publication.

Ultimately, what we discovered is that these researchers believe this release of aquacultured tangs has broad implications beyond the realm of aquarium keeping, far into the uncertain future of the world’s oceans and the life that dwells within.

CORAL: With the reality that the wild harvest of Hawaiian Yellow Tangs has been off-limits for several years, captive-bred (aquacultured) Yellow Tangs have been the only option in the aquarium trade. Veteran aquarists know that the price of an aquacultured Yellow Tang is substantially higher than the fish that were historically once harvested from the wild. Meanwhile, the ongoing battle over the Hawaiian aquarium fishery has been in front of aquarists for years, and as such, CORAL readers are likely more invested and aware of this topic than others. Still, it was surprising that this news quickly became one of the most viral stories we have ever shared on social media. We want to note that despite what is clearly a vocal minority, the response was overwhelmingly positive; for example, at the time of writing, cumulative Facebook reactions (Like, Love, Care, Wow, Sad, Angry) could be summarized as roughly 2,000 approving, with just 3 in opposition!

Still, the comments…

Callan: People just seem to gear towards negative commentary on the Internet these days. Everybody is looking to try to tear others down and say something bad about a group, rather than taking them at face value when they’re trying to accomplish something. Aquariums are under attack by watchdog groups. The same groups that are trying to keep the aquarium trade from opening up in Hawaii are also attacking public aquariums. They’re definitely hyper-focused, and I think the public is, to some degree, hyper-focused as well. And it’s just a society thing, too…people just like to troll on the Internet.

We’ve long held a fairly neutral stance on the whole Hawaii aquarium collection ban. We side with the State as far as the data has shown that the aquarium fishery has been managed to the point where the numbers that are being collected appear sustainable over protracted time periods. From that standpoint, the fishery could be considered sustainable. However, we agree that there are places that have lower numbers of fish than may be desirable, and so we feel there is a place for aquaculture as well as a place for well-managed, sustainable fisheries. We’ve never advocated for anything different.

There is a disconnect between the stakeholders: collectors, [aquaculturists/researchers], and conservationists. First of all, there’s not that many [marine ornamental aquaculture facilities]; there’s only one place breeding Yellow Tangs. There is still a lot of animosity between the fish collectors and the conservation groups that are trying to keep them from going back to business, and the breeders are being caught in the middle. The environmental advocacy groups that are very opposed to wild collection [are fighting against] the collectors who have done all of their due diligence to get started again, and the State is caught in the middle between lawsuits. The research organizations are caught in the middle, because we’re upsetting the conservationists by not doing enough breeding, and we’re upsetting the collectors by doing too much breeding.

Oceanic Institute is a research organization. Its mission is to conduct R&D. It’s not an advocacy group; we don’t have an agenda. We’re just trying to do good research and that’s the basis for what we do.

Davis: Aquaculture is not immune to the [issues of the aquarium fishery]. We need to collect wild fish for broodstock.

CORAL: More than one public comment framed OI’s release of the tangs as a PR or publicity stunt. How do you respond to that criticism?

Callan: I wouldn’t call it that. I know it’s a fine line, but we weren’t doing it to promote ourselves. We were doing it to promote the idea. I think there’s a subtle difference there that matters.

Honestly, from my perspective, it really had nothing to do with promoting the Institute. I think it was Spencer and Katie getting really excited that we got to the point where we came full circle in their minds. [Nearly] ten years ago we figured out how to breed the fish. It’s taken this long to get it to the point where we now have enough fish where we could conceivably put some back into the ecosystem. This was a “coming to awareness moment”, “isn’t it cool that we’re at this point now?”

Hiew: It definitely was not meant to be a PR stunt. I’ve been working with this fish for over seven years, I’ve done my thesis on this fish, and I’ve helped raise these babies. This was a monumental moment for me. We’ve been working on this fish for less than a decade. It was so huge being able to settle them for the first time. [Our work with Yellow Tangs] has helped us be able to settle so many other species. We never even would have thought of [releasing aquacultured Yellow Tangs into the wild] as a possibility before, and to now have cultured fish that we could release with the potential for ecosystem restoration? In no way were we saying that 300 fish would help the population. Yellow Tangs are one of the most studied fish in the industry. There’s tons of data. We are fully aware that their populations are fine. This was a very targeted release to a specific location.

It was a full circle moment for us and our team to be able to see how far we’ve come, and to be able to do exciting things. [This first release was] a way to address some social, ecological and regulatory concerns to show that this is something that aquaculture can do. Let’s try to make a path forward for this and figure out the logistics of how we can do this well, and safely, to be able to support the environment. Not because Yellow Tang numbers need it, and not to say “Hey, look at us.” It was sad for me to see all the negative remarks. Plenty of people had fair points, and this started a conversation, and it’s a welcomed conversation. We want aquaculture to be out there and in the news, we want people to be thinking about it. Still, it was disheartening to see the false information due to lack of knowledge about certain things, and to see how it kind of turned [negative] on that.

Davis: This isn’t necessarily a Yellow Tang thing. The Yellow Tang was what we had the opportunity to use based on how our hatchery was operating at the time. The parties involved—aquariums that we receive eggs from, sources of funding that we’re doing larval rearing for, our own interests as an aquaculture facility—we were all interested in the concept of releasing cultured fish and the possibility of it being sanctioned [by the State]. What use could this tool be put towards? Is it even possible to do? To that end, I was the one who sought State advice, sought permitting, and asked the questions about the implications of releasing cultured fish into the wild. There were a lot of considerations to make sure we did no harm. The Yellow Tang fit all the criteria, and so they were available for us to use in this proof of concept…The fact that we’re talking about this means our initial release was a success, because that was [one of the main purposes of this effort], just to get the topic on the table for conversation and make sure the doors are open for future species. Someone needed to break the ice.

CORAL: An icebreaker to start the conversation, indeed. We’ll come back to the idea of future species in a bit, but first let’s focus on the release of Yellow Tangs. So you were doing this to create an awareness of the possibilities, which is where the idea of this release being a “proof of concept” comes in.

Callan: This release wasn’t just done [like us thinking] we have these extra fish, let’s just throw them in the ocean. The team at OI is keenly aware of all the important factors that have to be taken into consideration for putting [a fish reared in] a lab into the ocean. There are disease issues, genetics issues, and all the required State buy-in.

CORAL: So walk us through the process of being allowed to release aquacultured fish. One of the comments online expressed frustration with the idea that a private person can’t do this but the University can, as if the State was somehow hypocritical or that the University was being allowed to break the rules? Where do you see the value in the regulation and level of hoops you had to go through?

Davis: Actually, a private person can indeed do this if they culture fish, approach DAR, and submit for a special activities permit, and check all the boxes. I didn’t even mention the University; I just went through all the hoops. So if a private person had fish that they wanted to release, I guess aquacultured or not, they’d still have to get all the approval through DAR.

CORAL: So how long did the permitting process take?

Davis: Well, this isn’t the first species that we’ve released. The original special activities permit took, all things considered, about a year. There are multiple steps along that path. Just the special activities permit for releasing fish in general took a while, and then I was able to get a case-by-case approval for new species. So, when we decided that we should try Yellow Tang, it took time to get [the State] to come out, do an inspection, and then get approval.

CORAL: So, as Chad said, this wasn’t just a random, willy-nilly decision to throw some fish into the ocean.

Davis: By the nature of our contract, we grow batches of eggs from public aquarium exhibits, which are mixed species, and when you do get [some fish], you spread that information to your partners and see who wants to take what, and when there’s extra [fish], then you have to decide what to do with them. With Yellow Tang, you know if you have extra maybe 70 days in when they settle and turn yellow. When we knew there were extra, we were lucky to have already started on the special activities permit for a similar release. So it still took some time after that to get our Yellow Tang approved for release, but we had already been far along in the process.

CORAL: This is a great moment to ask a question that readers and the public want answered: Why weren’t these fish released into the aquarium trade instead?

Callan: In this particular case, the project that funded the production of these fish had the requirement that the fish either go to educational facilities like public aquariums, or were used for some other common public good, but that they weren’t just released into the aquarium trade for sale. We had done a lot of due diligence, and most of the cohort was sent to aquariums around the U.S., and then the funding source said, “Hey, if you have extra, and you want to do this release, go for it.” So ultimately, it was the directive of the people funding the project.

CORAL: So what is the State looking for when it comes to determining whether this release could occur and be sanctioned?

Callan: The main concerns for releasing hatchery fish are genetics and disease, and they’re warranted.

CORAL: Explain the genetic concerns.

Davis: Is the species that we’re growing native [to where we intend to release it]? Are its genetics from local populations? We had to check the natural range of the parents, and consider where the parents were collected from. What would be bad is if someone had collected Yellow Tang broodstock that were the rare case of a non-Hawaiian Yellow Tang. [It wouldn’t be appropriate] if those were used as parents, although even in that scenario there’s probably no ill effect because the number [we released] was so small. But we don’t want to cause any type of change to the natural population genetics. We wanted to make sure that it was right, and so we checked the parentage and yes, [the Yellow Tang broodstock] had been collected from around Oahu.

Callan: Not only are [the Yellow Tangs we released] genetically compatible with the fish that are from that area, there are also way too few fish [in the initial release] to be even a blip in the genetics of the population. So from an origin perspective, and a math perspective, the genetic concerns are nil.

CORAL: OK, and what about disease concerns?

Davis: Disease is the other issue that was not only checked by us, [but also by] a third party with the State biologist before permitting. There are also checks and balances in place to prevent disease from even entering the hatchery.

Callan: The disease [concern] is probably the one that has the highest degree of risk, but the fish came from a biosecure facility where they’re routinely screened for any type of external parasites. We also sampled gill clips from some of the same cohort to make sure there weren’t any internal parasites. And then the state biologist looked at them for bacterial issues or any other cause for concern. Was the risk zero? No. But was risk mitigated to the greatest degree of our ability? Yes.

CORAL: Are there any other concerns you or the public might have over releasing fish into the wild?

Callan: [Another concern] people could have is the domestication of the fish. Yes, there are domestication effects. They’ve seen that with salmon and other species that are released; they look for pellets that fall from the sky for the first couple days of their life in the wild, and then eventually they figure it out.

CORAL: Can aquacultured Yellow Tangs adapt to the wild?

Callan: I don’t know why they wouldn’t. We don’t know for a fact because this is the first time that they’ve been released into the wild. However, releasing hatchery-produced fish into the wild is not new. It’s been done for hundreds of years. The first trout hatcheries were done in the 1800s. This is not a new concept. There’s a high probability that some of the Yellow Tangs will adapt and survive, there’s also a reasonable probability that many will get eaten, or perish from other causes. They’re not guaranteed to survive, but they’re not guaranteed to die.

CORAL: So with the checkboxes of disease and genetics met, the State gave the go-ahead to release these Yellow Tangs.

Callan: The State gave us the go-ahead. They looked at the risk versus impact potential, they gave us the green light, and gave us the permit. We obtained a special activities permit specifically to do this activity, and we did it exactly how any other organization would have to do it. Ultimately, it is fair to convey that all the main points of contention were clearly addressed.

Davis: Maybe it didn’t come across in the first news release, how much thought we put into it. We’re all ocean lovers here, and the last thing we’d want to do is any harm. That was the first question: are we doing anything wrong? When all signs pointed to no harm would happen, then it was logical to ask what good can come from this? There’s a lot of potential.

CORAL: We want to discuss that future potential, but first, turning to the release, how old were the Yellow Tangs that went into the ocean?

Callan: They were probably around three months old. They were little, about the size of a quarter, 90 to 100 days old.

CORAL: It wasn’t readily apparent in the initial news release, but the tangs OI released were actually released at more than one location over a couple of days at the start of November, 2024. How were the stocking locations selected?

Davis: [We] chose locations [that offered] somewhat ideal nursery habitat. If you release Yellow Tangs over a sandy bottom you might not see success. But if you find a structure to release them into, that’s a different story.

Hiew: The release we did on our side of the Island is an area that I snorkel fairly frequently. It’s an area that has some habitat that would be good for the Yellow Tang. There are some Yellow Tangs there…but the numbers of Yellow Tang that we typically see there aren’t massive… For me, that was a good indicator that this would be a good habitat that they could thrive in.

CORAL: Many, including CORAL Editors, wondered if there was any plan for follow-up study on the fish that were released. Is OI going to be able to address whether the Yellow Tangs released make it in the ocean? What are the future plans?

Callan: No, they were just released. It wasn’t part of a funded project to release them and then track their survivability. It really was done more as an awareness, outreach effort.

Hiew: We would have loved tagging or follow-up, but the State didn’t have the resources and didn’t want to put in the effort toward that. So, this is just the first step so that we can do more science-based research, future releases, and learn from all this…If we had the funding and resources to be able to do it, I would love to [conduct post-release research]. There’s already been a lot of data collected on Yellow Tangs, so maybe we don’t need more, but in my mind we always need more data. So, I’d want to know from these cultured fish, how long do they survive out there? Are they able to eat well and survive well and avoid predators? Do they survive to reproduce? How many of them do? There is so much data that we could learn from these that would be valuable and useful information for the future.

CORAL: Would it be possible to do a tag, release, recapture type project with Yellow Tangs?

Davis: [Researchers] have tried lots of different tags with Yellow Tang, and they don’t necessarily do well with them. They reject certain tags. One thing that we have done here in the past is to use [Visible Implant Elastomer Tags]. These are fluorescent tags that we put between their fin rays on the caudal fin. For some of our individuals, perhaps 50 percent, [these tags] have held and they’ve held for years now. But on others, the tag came out. So, if someone wanted to pursue this, they would need some funding for a research project to find the best method for tagging Yellow Tangs.

[If we could solve the tagging problem], I personally want to know if the tangs are staying in the locations where they are released, and how are they interacting. I want to be able to visually identify them and see if they’re contributing to eating algae on the reef. Are they swimming around with conspecifics?

Something I’m really interested in is artificial reefs that have been proposed here in Hawaii for coastal erosion protection from wave action, but also artificial reefs proposed for conservation in some areas. I think it would be great to stock aquacultured fish along with the installation of artificial reefs, and see if they stay affiliated with them.

CORAL: Throughout our conversation, both on and off the record, along with public commentary, there is this topic of “stock enhancement” and population restoration which drew a lot of attention, including criticism, concern, and confusion. And there is also this topic of future prospects. I think we’ve settled the notion that this release was not a PR stunt, and that Yellow Tang populations are not of concern, but instead that this represented a sort of next step. So what are these possibilities, this future which is being alluded to?

Davis: The term “stock enhancement” is probably misused in much of the conversation, but it’s the only term we have for releasing these fish. We’re not actually enhancing a stock when only releasing 300 fish, but that term has been used in the past to describe releasing cultured fish into the wild.

When you’re considering a species for release, it has a purpose. It’s very clear right now that for Yellow Tang, that purpose of our release was not conservation, and it’s not even fisheries enhancement, because the environmental impact study clearly demonstrated that the species is not in need and that the fishery is sustainable.

Callan: I think people got in a little bit of a huff when OI shared the story of releasing Yellow Tangs in the environment, being perceived as “There needs to be Yellow Tangs released because there are not enough in the wild,” and we weren’t saying any of that. It’s only 300 fish in a very big ocean. [Editor’s note: For comparison, in 2015 a DLNR report estimated the population of Yellow Tang on the west coast of the Big Island to be greater 6.1 million Yellow Tangs]. But, what [the release accomplished was to get] peoples’ attention. From that standpoint, it was impactful in that we’re having this conversation. The State is now aware of the fact that coral reef species, other than species used for food, could possibly be released and added to the reef habitat. Up until now, that wasn’t even on [the State’s] radar screen.”

CORAL: Perhaps, Chad, you put it best when, in our conversations, you asked the rhetorical question, “Is there a place for aquarium fish stock restoration on this planet?” What does the stocking of marine life look like in Hawaii?

Callan: The last stock enhancement that was done purposely in Hawaii was done in the ’90s with Moi (Pacific Threadfin, Polydactylus sexfilis) and Mullet (Mugil cephalus), which are two species that are culturally significant and significant for food in the recreational and subsistence fisheries here. There are plenty of published papers on the outcome. Basically [the program] showed a relatively significant impact in the fishery: 20–30 percent of the fish that were caught downstream, after the releases, were actually shown to be from these releases. So it made a meaningful difference in the nearshore fisheries. It had a positive impact. It was shown that it could work, but it wasn’t sustained due to funding reasons, and perhaps fell out of favor with the public and legislature, so it basically stopped around 2005. And so just now, the State is kind of discussing this again.

Davis: There’s an ongoing urchin out-planting project in Hawaii utilizing [aquacultured] Collector Urchins (Tripneustes gratilla), a native species…and that’s ongoing. [Editor’s Note: In partnership with the academic, state, and federal partners, the Anuenue Sea Urchin Hatchery had reached the incredible milestone of seeding one million juvenile collector urchins as of February, 2023. The urchins consume and control the smothering algae Kappaphycus alvarezii, which was originally brought to Hawaii for cultivation to produce carrageenan; if left unchecked, the algae quickly smoothers the reefs where it is present.]

CORAL: So how does this small release of Yellow Tang factor in?

Hiew: In my mind, this release of Yellow Tang created a path for the State where they used to do this before, but it hasn’t been something that’s been done with something like Yellow Tang which aren’t a foodfish, aren’t recreational, they’re part of the ornamental trade. There hasn’t ever really been a path for this to happen. And so, in my mind, this was a way to try and work through everything.

Davis: It really set the precedent that if we want to keep doing this for other species at larger scales that we need to continue to check all the boxes. So the result [of this Yellow Tang release], if we could say there is a result, is that we did it, and we didn’t do it illegally. We did it legally and it’s anecdotal, but we’ve had approval from experts in the field. We know the most tangible result is that more people are talking about it. If people are thinking about this concept when we go to do more, it’s a win. We’re just reintroducing this concept of releasing [aquacultured] fish again.

CORAL: OK, so finally, let’s talk about the future, and other species. Does something like the ongoing Yellow Tang aquaculture research help inform the work with other species?

Callan: [Consider] the Coral Trout (Plectropomus leopardus). It looks like the Miniatus Grouper (Cephalopholis miniatus) but it’s not closely related. Coral Trout is really popular in Asia in the live reef fish food trade. It’s been heavily overfished in its natural region. Aquaculture methods for it have been tried for a decade or so and no one has had any good success with it. We applied some of the methods we used for the Yellow Tang to that species and we got the survival from a mere 1% up to 10%. So, there are now fingerling production methods for that species that are hopefully going to be applied in Australia, the Philippines, wherever the species is naturally occurring.

Davis: The methods that we developed for culturing the Yellow Tang are directly applicable to a number of other fish species. We’ve used similar methods to culture butterflyfish, grouper, and wrasse, you name it. The live feeds, the hatchery methods, the lighting regime, all the things like that, we’ve kind of made a cookbook protocol that we can then adapt to different species.

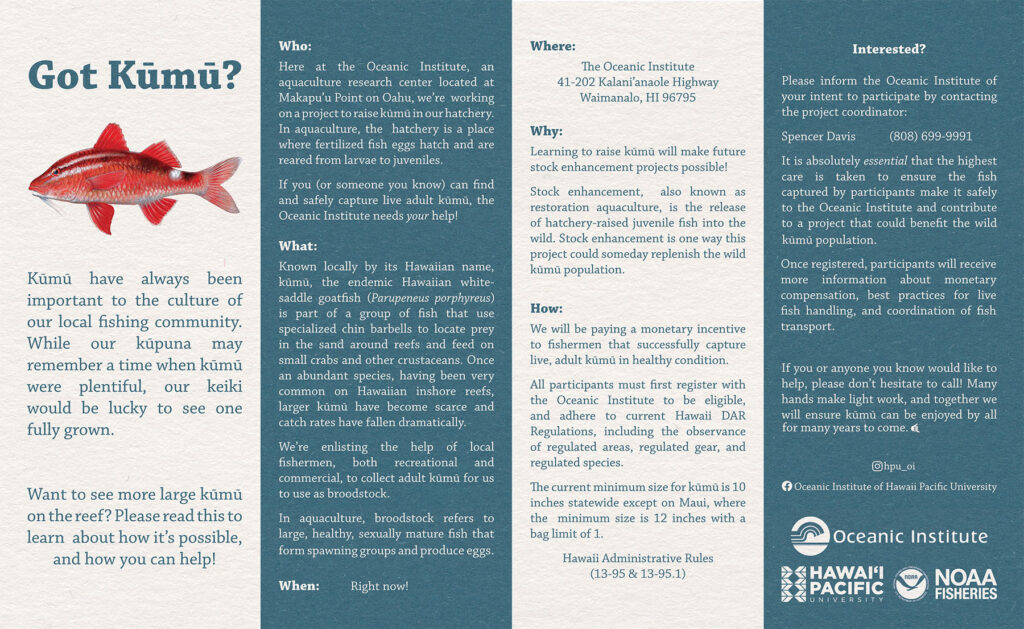

CORAL: So explain the kūmū project that is currently underway at OI, the kūmū being the endemic Hawaiian Whitesaddled Goatfish, Parupeneus porphyreus. While goatfish are kept in aquariums on occasion, this species isn’t considered an aquarium subject. Yet it’s definitely of interest.

Callan: Their population is very depressed. Whether it’s from overfishing or habitat change, it’s up for debate. But there are not many of them out there, so we’ve developed a program to look at trying to develop captive breeding methods for them. We haven’t been successful yet in producing any juveniles so it’s proving to be a very difficult species to rear.

The project is still ongoing. We’re still trying to develop culture methods for that species. If we are successful in producing juveniles, we have a grant and permission from the State to do a very limited amount of tag and release of those juveniles so that we can try to understand their survival and where they go, to inform a bigger program down the road. But these are baby steps for that species.

CORAL: So with something like the goatfish you just have to figure out where it’s falling short, and tweak?

Callan: What we think with them is that they typically spawn in cooler times of year. The larvae seem to require cooler water. Our hatchery wasn’t set up to do lower temperature flow-through water, so we’ve made some different changes to our system as far as temperature and lighting, those seem to be making a difference for those goatfish. We think by tweaking just a few of those things, we’ll be able to get them through.

CORAL: The work you’re doing with these goatfish, I think you probably just view it all as aquaculture. You don’t draw a line between ornamentals and foodfish, it’s all just fish breeding to you.

Davis: What you’re getting at is that aquaculture of any fish, the process of propagating marine fish species, can be used not just for commercial trade.

CORAL: And in this instance, the aquarium trade’s interest in Yellow Tang is driving research and positive outcomes well beyond that aquarium hobby.

Callan: It’s all for the same purpose in my mind. For market, for food, for conservation, they can be used interchangeably.

Davis: [And whether it’s for] recreational fisheries enhancement, [or for] conservation for a species that’s in population decline like ku¯mu¯, future release of any fish species is going to face more scrutiny than previous stock enhancement programs. In the past, meaning 20 or 30 years ago, [the Mullet and Moi programs were] successful. It was shown that they weren’t affecting wild genetics, and it was shown that they were increasing fisheries yield.

Those programs were actual “mid-scale” stock enhancement, [releasing] something like 80,000 fish each year. The response we got on social media for releasing 300 Yellow Tangs might indicate the kind of scrutiny that an actual future stock enhancement program might face in today’s climate.

We had to go through all sorts of hurdles for the goatfish broodstock. The goatfish that were collected were above regulation size, they were not collected from regulated areas, they were not collected using regulated gear, it was otherwise all legal if they were put on ice. But because they were live—even though they’re not a traditional aquarium fish—they were alive and transported live so I had to get special activity permits.

So what we did with the Yellow Tangs, whether proof of concept or [whatever someone calls it] was to raise awareness of what it takes now to release any number of fish. It was a proof of concept even for ourselves, to show our partners and the community that it’s actually possible these days to still release these fish following all the right precautions and following all the right regulatory steps.

So, the implications for the future, for the ku¯mu¯ project we’re currently working on, this Yellow Tang release will be on the mind of regulators. Are we taking a responsible approach? I’m really glad that, contrary to the vocal minority’s concern, we followed all the right steps.

Hiew: [The release of these Yellow Tangs] was such a meaningful and important moment for us. We’re so passionate about aquaculture, including ornamental aquaculture. If we can all have these conversations, and we can all work together, that’s how we get somewhere.

CORAL: Thank you all for sharing your thoughts and experiences. For CORAL readers who would like to learn how to support the work at OI, helping fund projects such as the kūmū aquaculture research effort, please visit: www.hpu.edu/oi/support-oi.html

Online

Find links to more information about the kūmū project, Collector Urchin stocking to control invasive algae, and share your comments, all at CORALmagazine.com/tangrelease24