by CORAL and AMAZONAS Contributor Art Parola

The Endangered Species Act[1] (ESA) is likely the second most misunderstood piece of legislation impacting the aquarium hobby and trade. (The first is unquestionably the Lacey Act, which is incredibly complex, has disjunct codification under two different Titles, and is one of the broadest criminal statutes in the entire U.S. Code, albeit mostly under the environmental law title and not the criminal law title.) The goal of this article is to summarize the framework of the ESA in a way that clears up some common misconceptions, such as whether the law applies to both wild-sourced and captive-bred animals, and what and when certain lists have legal authority.

The IUCN Red List

There is often confusion about what the term “Endangered” means. It gets particularly confusing when it comes to “listing of Endangered Species.” A species can be listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, which is (supposed to be) a purely scientific system to categorize the extinction risk of species using certain criteria. To lessen confusion, it is probably best to refer to IUCN designations as “categorizations” instead of “listings.” IUCN Red List categorizations have no legal authority. IUCN Red List categorizations of a species and the associated data may be used to inform listings on lists that do have legal authority such as listing under the ESA and on the (Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species) CITES Appendices, but these lists are completely separate and serve different purposes. In addition, there are different criteria used to determine if a species is categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List than those criteria used to list a species as Endangered under the ESA.

If a species is categorized as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, this does not mean that it is legally listed as Endangered under the ESA. For example, the Tequila Splitfin (Zoogoneticus tequila) is categorized as Endangered[2] on the IUCN Red List. The Tequila Splitfin however, is not listed as Endangered under the ESA thankfully, as the associated restrictions would have likely hindered the reintroduction program, which utilized progeny of genetic lines kept alive by aquarium hobbyists.

Similarly, the Redtail Shark (Epalzeorhynchos bicolor) is categorized on the IUCN Red List as Critically Endangered[3]. However, as with the Tequila Splitfin, the Redtail Shark is not listed as Endangered under the ESA and, therefore, is not subject to legal restrictions on import and interstate commerce in the United States. This again is very fortunate for this species as habitat degradation and dams are the main threat to the species, but demand from the aquarium trade ensures it will never go extinct as large commercial fish farms raise millions to supply hobbyist demand.

Somphong’s Rasbora (Trigonostigma somphongsi) is in a similar situation, being categorized as Critically Endangered[4] on the IUCN Red List due to habitat degradation, but not listed as Endangered or Threatened under the ESA and not listed on the CITES Appendices. Somphong’s Rasbora is, therefore, not subject to legal restrictions for import or interstate commerce. (The White Cloud Mountain Minnow (Tanichthys albonubes) is categorized on the IUCN Red List as Data Deficient[5] and is not listed under the ESA either, meaning it can be freely imported and traded in interstate commerce as well.)

Some species of interest to aquarists are not listed under the ESA but are included on the CITES Appendices. Elegance Coral (Catalaphyllia jardinei) is categorized as Vulnerable[6] on the IUCN Red List. It is not listed as Endangered or Threatened under the ESA, however, international trade is regulated through CITES. Elegance Coral is listed under CITES Appendix II along with all Scleractinia Corals. Open Brain Coral (Trachyphyllia geoffroyi) is categorized as Near Threatened[7] on the IUCN Red List. It is not listed as Threatened or Endangered under the ESA. It is regulated in international trade by CITES as Appendix II species.

While it has already been stated, it is worth reiterating that, while IUCN Red List categorizations can inform listings on the ESA Endangered and Threatened list and CITES Appendices, the IUCN categorizations are not legal determinations. Categorizations on the IUCN Red List do not carry any force of law. An IUCN Red List categorization of Endangered is not at all equivalent to an ESA listing of Endangered. The former is a scientific determination, and the latter is a legal determination.

The Endangered Species Act (ESA)

Unlike the IUCN Red List, the ESA carries the force of law to anywhere and anyone under the jurisdiction of the United States. The ESA is legislation, passed by Congress and signed by President Nixon in 1973. The statute describes the purposes[8] of the law, lays out a framework for determining[9] species that are Threatened or Endangered, describes prohibited[10] acts in regard to those species, and attempts to provide the legal infrastructure to lay a path to recovery of those species listed. It also codifies into US law[11] the regulations of the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), the United Nations treaty that regulates the international wildlife trade to ensure such trade is not threatening species with extinction.

While Congress wrote the statute of the ESA, it delegated certain powers and responsibilities to Executive Branch agencies to list species and promulgate certain regulations. Congress tasked US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) with managing listings and regulation of terrestrial and freshwater species, and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) (often referred to as NOAA Fisheries) with the same for marine and anadromous species.

The criteria for listing determinations are based on five factors[12] using the best available scientific and commercial data:

- the present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of a species’ habitat or range;

- overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes;

- disease or predation;

- the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or

- other natural or manmade factors affecting a species’ continued existence.

The respective agency will use these five factors to determine if a species is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range in which case it will be listed as Endangered under the ESA. If the agency determines the species is likely to become an endangered species in the foreseeable future, the respective agency will list the species as Threatened under the ESA. There is also a third way species can be listed under the ESA. The statute has a similarity of appearance provision that allows agencies to list a species under the ESA if it looks like another species that is listed as Endangered or Threatened under the ESA. Congress set out certain procedures the agencies must follow during the listing process and when promulgating related regulations. These include certain requirements to give notice and receive public comment. The regulation that lists all currently ESA listed Endangered and Threatened species is 50 CFR 17.11[13].

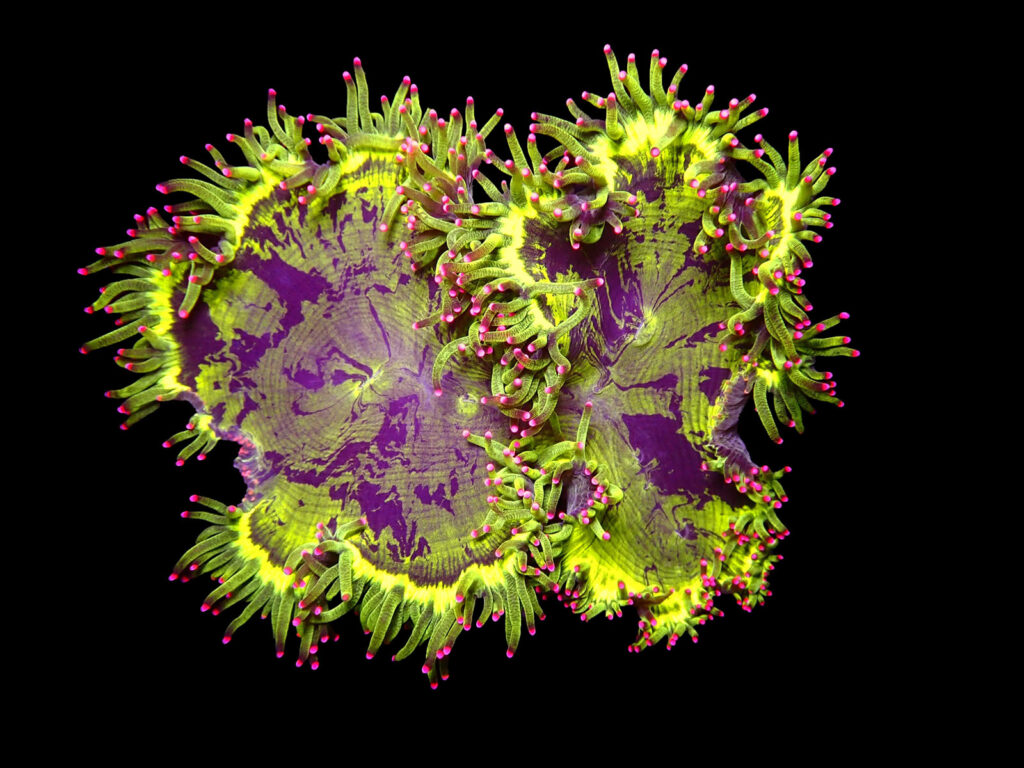

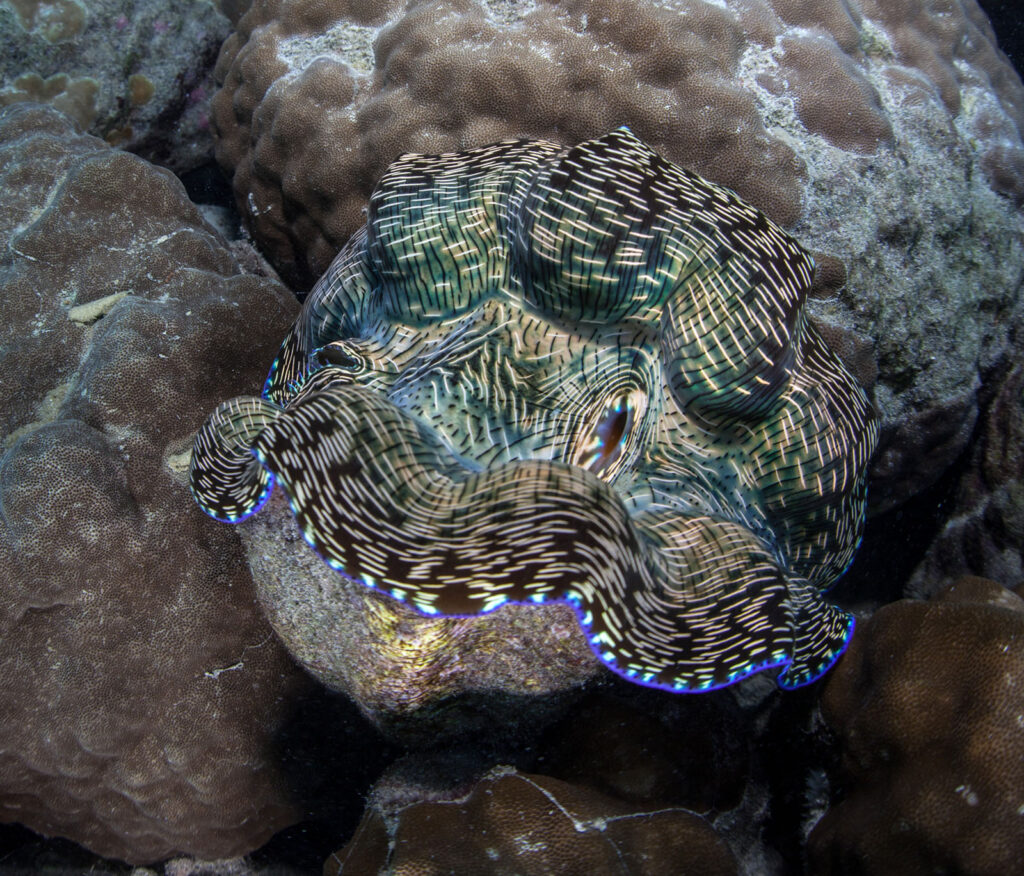

Any species listed as Endangered under the ESA is subject to the restrictions set out in Section 9[14] of the ESA. This includes prohibitions on importing into or exporting from the United States and selling in interstate commerce. These restrictions apply to all members of the species, whether from captive-bred or wild sources. Individual organisms from captive-bred sources are not exempt from Section 9 prohibitions. This is why, despite being captive-bred in large numbers and CITES regulations allowing legal trade, Asian Arowana (Scleropages formosus) are prohibited in the United States. While Congress did outline a few exemptions to the prohibitions, exemptions are not given for commercial activity of captive-bred aquarium species, regardless of whether there is a conservation benefit. If the proposed rule[15] to list giant clams such as Tridacna derasa and T. gigas as Endangered under the ESA is finalized, breeding and restocking benefits derived from the aquaculture of these species would not exempt them from the Section 9 prohibitions on import and interstate commerce, regardless of whether the source is wild or captive bred. All commercial activity in these species will cease.

When a species is listed under the ESA as Threatened, federal agencies have more discretion to tailor regulations. This regulation is called a 4(d) rule because the authority to make such regulation stems from Section 4(d) of the ESA statute. The agency has the option to promulgate regulation applying full Section 9 prohibitions to a species through a 4(d) rule, prohibiting import, export, and interstate commerce and resulting in the same legal outcome as if the species has been listed as Endangered under the ESA. An agency can at times promulgate less restrictive regulation through a 4(d) rule, such allowing interstate commerce but prohibiting import or export of a species. This was essentially the recent 4(d) rule proposed by NMFS for Banggai Cardinalfish. A 4(d) rule can also allow certain forms of a species to be traded in commerce but disallow others. For example, in the recent giant clam listing proposal, a 4(d) rule was proposed for Tridacna maxima that would allow import, export, and interstate commerce in live specimens, but would prohibit import, export, and interstate commerce in frozen meat and carved shells. Promulgating a 4(d) rule is only an option for species listed as Threatened under the ESA. All Section 9 prohibitions are automatically applied to any species listed as Endangered under the ESA.

In addition, the listing of a species under the ESA by the federal government triggers laws in some states that prohibits possession, transport, sale, and other activities with a species in the state. For example, under Michigan state law,[16] a species’ listing as Endangered or Threatened under the ESA triggers a prohibition on possession, transport, import, sale, and several other activities. There are some limited exceptions in the statute, but these would not apply to someone keeping ESA listed species in an aquarium or selling such species in a pet shop. As with federal law, the state law does not discriminate between individual organisms from wild or captive-bred sources. The prohibitions apply to captive-bred individuals. While it is likely enforcement of such provisions is rare, violations constitute a misdemeanor, punishable by up to 90 days imprisonment and/or up to a $1,000 fine.

There is an argument to be made that the Michigan law is void regarding nonnative animals, listed under the ESA as Threatened with federal regulation that allows for interstate commerce in the species. There is case law[17] that supports the argument that Congress preempted the states from enacting conflicting regulations for such species and therefore sale and possession must be allowed in line with federal regulations. Whether or not Michigan can apply its prohibition on possession, transport, sale, and import to species that are ESA listed as Threatened, but for which federal regulations allow interstate commerce, is unsettled law. This puts possession, transport, sale, and import of species such as Banggai Cardinalfish (Pterapogon kauderni), Branching Frogspawn Coral (Euphyllia paradivisa), and several other species of coral in Michigan into a legal gray area. If the proposed rule is finalized, it will also put possession, transport, sale, and import into Michigan of the giant clam species Tridacna maxima, T. noae, T. crocea, and T. squamosa, into this legal gray area.

Michigan’s prohibition on possession, sale, and import of ESA-listed Endangered species would not be preempted by federal regulations. This would criminalize possession, transport, sale, and import of any species listed. The statute does not contain a grandfather clause allowing continued possession of species possessed prior to the listing, so what would happen in these cases is unclear. This is a major issue, given that several species of great interest to aquarists are either proposed for listing as Endangered under the ESA, or are currently undergoing a review and will likely be proposed for listing in the near future. Such species include all giant clams not listed above (genera Tridacna and Hippopus) and two wild-type Betta species: Betta hendra and Betta rutilans.

Michigan is not the only state with such laws that are triggered by a federal listing. Several other states have similar laws on the books.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

As mentioned earlier, CITES regulations are codified and implemented into US law through Section 8A of the ESA. CITES regulations apply when wildlife crosses international borders, and do not impact domestic trade or transport within the United States. CITES has its own listing process, completely separate from the ESA. The CITES lists are broken up into three Appendices[18], each with its own criteria[19] for listing. Like the ESA list, these lists, while required to be based on scientific analysis, are not scientific determinations, but legal ones. The criteria for listings on the CITES Appendices not only take into account whether a species is threatened with extinction but, because CITES specifically regulates international trade, requires that international trade specifically be a threat in order for any species to be listed. (At least in theory, in practice CITES is often political and therefore the criteria are not always strictly followed.)

Species listed under Appendix I are species that are threatened with extinction by international trade, and therefore trade is prohibited except in certain circumstances and almost always prohibited from wild sources. Species listed under Appendix II are not necessarily threatened with extinction, but trade must be regulated to prevent overutilization that may threaten their continued survival. Trade is allowed in CITES Appendix II species, so long as each international shipment is accompanied by the appropriate CITES permit. To obtain this permit, certain regulations must be followed and specific requirements must be met.

One such requirement is that a Non-Detriment Finding (NDF) is conducted to ensure the trade in the individual organisms for which the permit is to be issued will not be detrimental to the survival of the species. Once an NDF has been conducted, a permit may be issued for the organisms to be exported. Permits may be issued for individuals from wild sources of species listed under CITES Appendix II so long as an NDF is issued. Being listed under CITES Appendix II does not necessarily prohibit commercial trade in wild-sourced specimens. For example, according to the CITES Trade Database[20] almost all Elegance Corals imported into the United States are from wild sources.

Several specific items are required to be listed on the permits, utilizing a series of CITES codes. Purpose codes denote the purpose of the transaction. Some examples include T (commercial), Z (zoo), S (scientific), P (personal), and N (Reintroduction or introduction into the wild). Source codes denote the source of the individual organisms to be traded. Some examples include W (specimens taken from the wild), R (Ranched specimens: specimens of animals reared in a controlled environment, taken as eggs or juveniles from the wild, where they would otherwise have had a very low probability of surviving to adulthood), F (Animals born in captivity (F1 or subsequent generations) that do not fulfill the definition of “bred in captivity”), and I ( Confiscated or seized specimens). Each permit must have both the correct purpose code and source code.

It is important to note that just because a species is listed on CITES Appendix I does not mean all international trade in the species is illegal. CITES Appendix I listed species can be treated as CITES Appendix II listed species[21] when the individuals to be traded, even for commercial purposes, are produced at a CITES-registered captive breeding facility and meet all other species-specific requirements. All transactions of animals in this situation are accompanied by a CITES permit with a source code D (Appendix I animals bred in captivity for commercial purposes in operations included in the Secretariat’s Register). This exception for CITES Appendix I listed species bred at CITES registered breeding facilities is the reason Appendix I species such as the Asian Arowana can be legally traded throughout most of the world, with individuals originating from CITES registered captive breeding facilities in several countries in Southeast Asia.

This exception for commercial trade in captive-bred individuals of species for which commercial trade is otherwise prohibited is a key difference between the CITES framework and the framework of the ESA. The flexibility this offers is one of the reasons CITES is so effective as a regulatory mechanism at achieving its goals of increasing populations of species whose existence might otherwise be threatened.

Law is complicated. The law applied to the possession, transport, import, export, and sale of aquarium organisms, at jurisdictional levels from municipal, to state, federal, international, and foreign, is no exception. Understanding it requires not just reading and interpreting a statute by its plain meaning, but also researching regulation, studying case law, observing legal canons, spotting conflicts, understanding procedure, and much more. Legal definitions are not always the same as what one would expect in common parlance, scientific definitions, or even the same as the same word used in other statutes. To make understanding the law even more difficult, many people magically earn a Juris Doctor the minute they log on to Facebook or plug in their podcast microphone and spread misinformation, muddying already opaque waters. Hopefully, this article helped clarify how the ESA and CITES work and dispel some common misconceptions, especially when it comes to the difference between the law and the IUCN Red List.

[1] https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/endangered-species-act-accessible_7.pdf

[2] https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/169395/1276460

[3] https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/7807/12852157

[4] https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/187886/8638137

[5] https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/166073/6165399#assessment-information

[6] https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/132890/3479919

[7] https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/133260/3659374

[8] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1531

[9] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1533

[10] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1538

[11] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1537a

[12] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1533

[13] https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/50/17.11

[14] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1538

[15] https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2024-14970.pdf

[16] https://www.legislature.mi.gov/Laws/MCL?objectName=mcl-324-36505

[17] https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11414737355944060010&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr

[18] https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php

[19] https://cites.org/sites/default/files/document/E-Res-09-24-R17.pdf

[21] https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/res/all/12/E12-10R15.pdf