Smashing Flowerpots: Sexual Propagation Success with Goniopora Corals

by Matt Pedersen with images from Inter-Fish Pty Ltd

An exclusive free excerpt from the July/August 2023 issue of CORAL Magazine.

The aquarium-keeping pursuit is perhaps one of the most exciting journeys of discovery and anyone can participate, even the amateur scientist at home. Every so often the aquarium world is jolted by a profound breakthrough in aquatic husbandry. We recognize this as one of those times.

When it comes to the flowerpot corals of the genus Goniopora, they have gone from being truly “cut flowers” that lived only months in captivity, to now thriving reef aquarium inhabitants that can be asexually propagated and shared. This dramatic shift in husbandry success all occurred in the span of less than two decades. And now, the aquarists at Inter-Fish Pty Ltd (Inter-Fish) have smashed through the final frontier of Goniopora husbandry, revealing their success in creating sexually propagated (captive-bred) Gonipora corals for the first time in aquarium history. CORAL Magazine discussed this breakthrough with Don Gilson, Principle and Managing Director, and Dr. Luchang Shao, General Manager and Lead Coral Spawning Scientist at Inter-Fish.

Matt Pedersen: Who is Inter-Fish Pty Ltd?

Don Gilson: Like many others in our trade, the fascination and love for the animals in our oceans started our journey at Inter-Fish. Our focus as a collector, exporter, and educational resource facility has centered around coral husbandry and long-term sustainability. We are truly excited that Inter-Fish is now actively contributing to coral spawning research and working to understand and protect these fascinating organisms for future generations to enjoy.

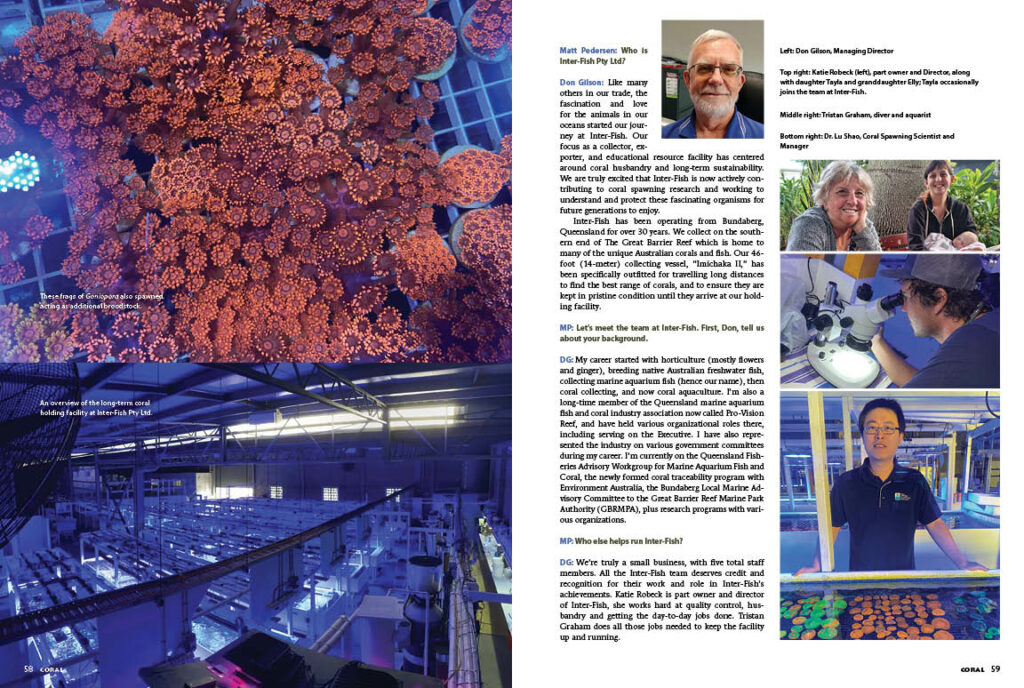

Inter-Fish has been operating from Bundaberg, Queensland for over 30 years. We collect on the southern end of The Great Barrier Reef which is home to many of the unique Australian corals and fish. Our 46-foot (14-meter) collecting vessel, “Imichaka II,” has been specifically outfitted for traveling long distances to find the best range of corals, and to ensure they are kept in pristine condition until they arrive at our holding facility.

MP: Let’s meet the team at Inter-Fish. First, Don, tell us about your background.

DG: My career started with horticulture (mostly flowers and ginger), breeding native Australian freshwater fish, collecting marine aquarium fish (hence our name), then coral collecting, and now coral aquaculture. I’m also a long-time member of the Queensland marine aquarium fish and coral industry association now called Pro-Vision Reef, and have held various organizational roles there, including serving on the Executive. I have also represented the industry on various government committees during my career. I’m currently on the Queensland Fisheries Advisory Workgroup for Marine Aquarium Fish and Coral, the newly formed coral traceability program with Environment Australia, the Bundaberg Local Marine Advisory Committee to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA), plus research programs with various organizations.

MP: Who else helps run Inter-Fish?

DG: We’re truly a small business, with five total staff members. All the Inter-Fish team deserves credit and recognition for their work and role in Inter-Fish’s achievements. Katie Robeck is part owner and director of Inter-Fish, she works hard at quality control, husbandry and getting the day-to-day jobs done. Tristan Graham does all those jobs needed to keep the facility up and running.

MP: Dr. Shao, please share some of your backstory and explain your current involvement at Inter-Fish.

Dr. Luchang Shao: I’m 37 years old, and hold a Ph.D. degree in Marine Biology and Aquaculture from James Cook University (JCU). I have worked for several institutions including the Marine and Aquaculture Research Facility MARFU at JCU, Aquarium Industries, Cairns Aquarium, Ultra Coral Australia, and presently serve as the Lead Coral Spawning Scientist and General Manager for us at Inter-Fish Pty Ltd.

I’ve been with Inter-Fish for three years, during which time I have utilized my research experience and professional background to develop an in-depth understanding of aquatic animal breeding and husbandry, with a specific focus on marine fish and coral aquaculture. My expertise extends to fish health and disease control, as well as the design, construction, and management of tanks, systems, and life support systems. I possess extensive knowledge of water quality monitoring and have accumulated nearly 14 years of experience in aquaculture, working with both small and large-scale recirculating systems and the associated equipment that runs these systems. I’m thrilled that I have an opportunity here at Inter-Fish to pursue my passion and enhance my knowledge of coral propagation and captive breeding. I look forward to what the future holds as we continue on this amazing journey.

MP: How does coral breeding factor into your business model, and how did Inter-Fish get started with breeding corals?

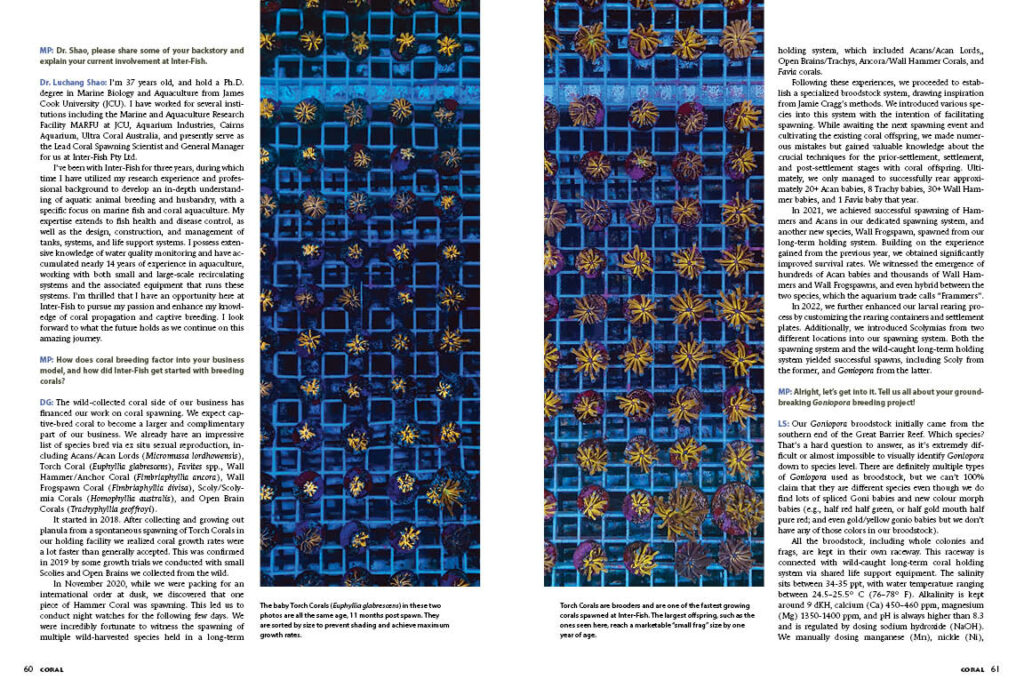

DG: The wild-collected coral side of our business has financed our work on coral spawning. We expect captive-bred coral to become a larger and complementary part of our business. We already have an impressive list of species bred via ex-situ sexual reproduction, including Acans/Acan Lords (Micromussa lordhowensis), Torch Coral (Euphyllia glabrescens), Favites spp., Wall Hammer/Anchor Coral (Fimbriaphyllia ancora), Wall Frogspawn Coral (Fimbriaphyllia divisa), Scoly/Scolymia Corals (Homophyllia australis), and Open Brain Corals (Trachyphyllia geoffroyi).

It started in 2018. After collecting and growing out planula from a spontaneous spawning of Torch Corals in our holding facility we realized coral growth rates were a lot faster than generally accepted. This was confirmed in 2019 by some growth trials we conducted with small Scolies and Open Brains we collected from the wild.

In November 2020, while we were packing for an international order at dusk, we discovered that one piece of Hammer Coral was spawning. This led us to conduct night watches for the following few days. We were incredibly fortunate to witness the spawning of multiple wild-harvested species held in a long-term holding system, which included Acans/Acan Lords, Open Brains/Trachys, Ancora/Wall Hammer Corals, and Favia corals.

Following these experiences, we proceeded to establish a specialized broodstock system, drawing inspiration from Jamie Cragg’s methods. We introduced various species into this system with the intention of facilitating spawning. While awaiting the next spawning event and cultivating the existing coral offspring, we made numerous mistakes but gained valuable knowledge about the crucial techniques for the prior-settlement, settlement, and post-settlement stages with coral offspring. Ultimately, we only managed to successfully rear approximately 20+ Acan babies, 8 Trachy babies, 30+ Wall Hammer babies, and 1 Favia baby that year.

In 2021, we achieved successful spawning of Hammers and Acans in our dedicated spawning system, and another new species, Wall Frogspawn, spawned from our long-term holding system. Building on the experience gained from the previous year, we obtained significantly improved survival rates. We witnessed the emergence of hundreds of Acan babies and thousands of Wall Hammers and Wall Frogspawns, and even hybrids between the two species, which the aquarium trade calls “Frammers”.

In 2022, we further enhanced our larval-rearing process by customizing the rearing containers and settlement plates. Additionally, we introduced Scolymias from two different locations into our spawning system. Both the spawning system and the wild-caught long-term holding system yielded successful spawns, including Scoly from the former, and Goniopora from the latter.

MP: Alright, let’s get into it. Tell us all about your groundbreaking Goniopora breeding project!

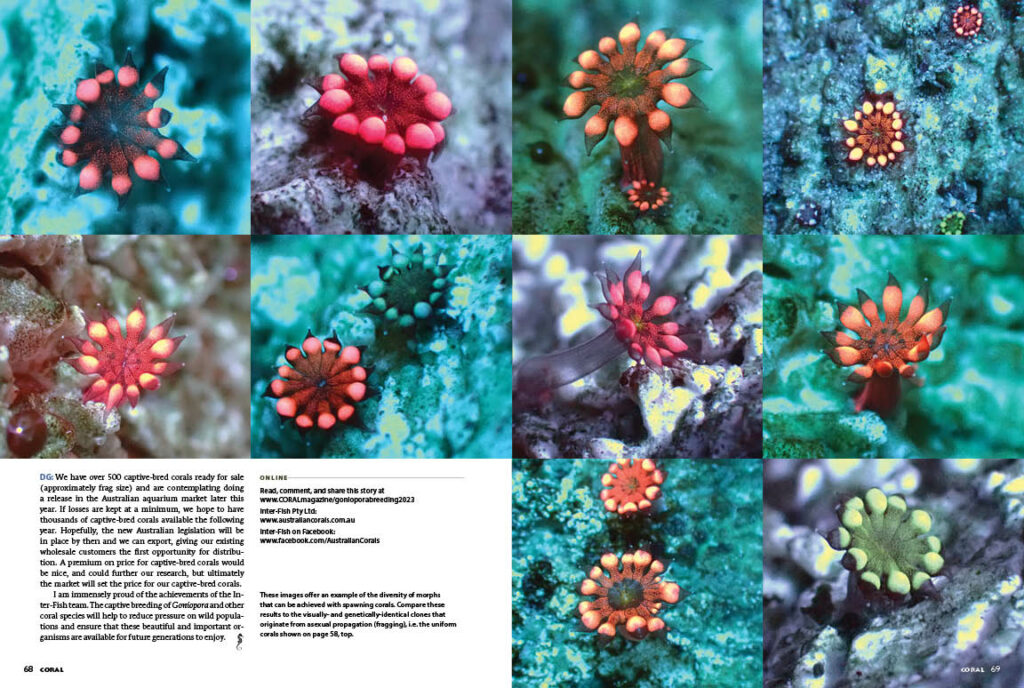

LS: Our Goniopora broodstock initially came from the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef. Which species? That’s a hard question to answer, as it’s extremely difficult or almost impossible to visually identify Goniopora down to the species level. There are definitely multiple types of Goniopora used as broodstock, but we can’t 100% claim that they are different species even though we do find lots of spliced Goni babies and new color morph babies (e.g., half red half green, or half gold mouth half pure red; and even gold/yellow gonio babies but we don’t have any of those colors in our broodstock).

All the broodstock, including whole colonies and frags, are kept in their own raceway. This raceway is connected with the wild-caught long-term coral holding system via shared life support equipment. The salinity sits between 34-35 ppt, with water temperature ranging between 24.5–25.5° C (76–78° F). Alkalinity is kept around 9 dKH, calcium (Ca) 450–460 ppm, magnesium (Mg) 1350-1400 ppm, and pH is always higher than 8.3 and is regulated by dosing sodium hydroxide (NaOH). We manually dose manganese (Mn), nickel (Ni), potassium (K), and iodine (I) individually, along with other combined trace supplements. We keep our nutrient levels under 0.2 ppm for nitrate, 0.02 ppm for phosphate by using carbon- and probiotic-dosing methods.

Lights were customized; spectrum includes 410nm, 430nm and 450 nm, PAR is around 100 to 140. We start with natural seawater, but to maintain a stable microorganism environment, we prefer not to do water changes, and these only occur when required for tank cleaning, etc.

MP: How did the Goniopora come to spawn?

LS: In late 2022, the broodstock colonies of Goniopora spawned, resulting in the survival and growth of over 10,000 juveniles during a six-month period. Remarkably, nearby frags recently cut from large colonies also spawned. But even more astonishing was that other small colonies from earlier cuttings, which had subsequently healed and encrusted, also spawned.

Regarding spawning triggers, we have found that species of corals spawn simultaneously with their conspecifics, regardless of their individual location in our systems. Whether the corals were held in our wild-caught long-term holding system, which maintained a consistent temperature without any other environmental cues, or the corals resided in our specialized brood stock system with a setup incorporating seasonal changes (such as moonlight cycles, temperature variations, solar irradiation, sunrise/sunset), all of the corals spawned synchronously. This observation has led us to speculate that the spawning triggers might be influenced by factors beyond our control, such as the moon’s gravity or the Earth’s magnetic field.

The collection of Gonipora spawn is very similar to what everyone else is currently doing for coral breeding projects. We collect egg bundles from the water surface on spawning night, cross-fertilize, and leave them in a 20-liter (5.3-gallon) bucket for the first night with static water. The larvae are then transferred into a 5-liter (1.3-gallon) customized larval rearing bucket with a gentle flow to keep larvae separate and suspended in the water column. 3-4 days after spawning, larvae are transferred again, now into settlement tanks with customized settlement plates.

12 days after spawning, there were no signs of zooxanthellae uptake in the baby Goniopora, and there was no transformation yet to a classic polyp shape. At 13 days after spawning, there were still no signs of zooxanthellae uptake, but “lines” were visible and the larval coral started shaping into a polyp.

18 days after spawning, we observed zooxanthellae around the mouth on some of the settled babies, although the majority of them still didn’t seem to have any zooxanthellae. But, by 26 days after spawning, almost every polyp had zooxanthellae. At 48 days after spawning, the polyps were fully filled with zooxanthellae, and we could see their perfect round calcium carbonate skeleton base.

52 days after spawning, white bands (six in total) show up on every second tentacle. This is very similar to baby Hammer Coral development where white dots first show up on every second tentacle. The appearance of these color patterns is the prelude to a large morphological change in the polyps, and the development of fluorescent pigments. These pigments (which, again, look like white bands under white light) start on every second tentacle, then spread to all 12 tentacles, and ultimately expand to the main mouth area.

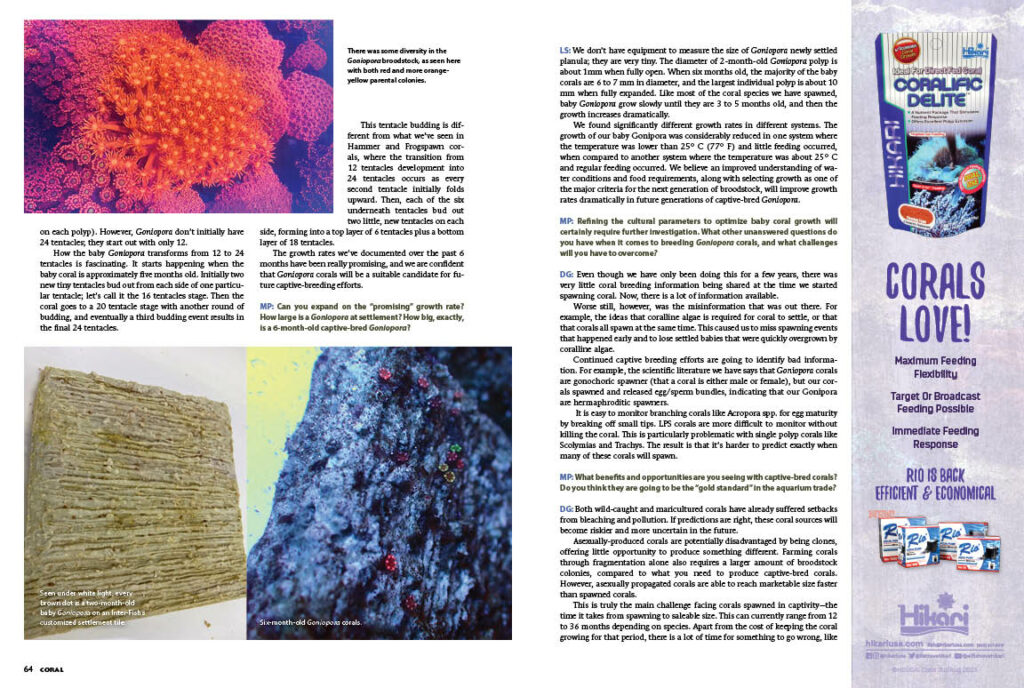

Goniopora have 24 tentacles, which is a useful characteristic that helps readily distinguish them from the visibly similar Alveopora (which have only 12 tentacles on each polyp). However, Goniopora don’t initially have 24 tentacles; they start out with only 12.

How the baby Goniopora transforms from 12 to 24 tentacles is fascinating. It starts happening when the baby coral is approximately five months old. Initially, two new tiny tentacles bud out from each side of one particular tentacle; let’s call it the 16 tentacles stage. Then the coral goes to a 20 tentacles stage with another round of budding, and eventually a third budding event results in the final 24 tentacles.

This tentacle budding is different from what we’ve seen in Hammer and Frogspawn corals, where the transition from 12 tentacles development into 24 tentacles occurs as every second tentacle initially folds upward. Then, each of the six underneath tentacles bud out two little, new tentacles on each side, forming into a top layer of 6 tentacles plus a bottom layer of 18 tentacles.

The growth rates we’ve documented over the past 6 months have been really promising, and we are confident that Goniopora corals will be a suitable candidate for future captive-breeding efforts.

MP: Can you expand on the “promising” growth rate? How large is a Goniopora at settlement? How big, exactly, is a 6-month-old captive-bred Goniopora?

LS: We don’t have equipment to measure the size of newly settled Goniopora planula; they are very tiny. The diameter of 2-month-old Goniopora polyp is about 1 mm when fully open. When six months old, the majority of the baby corals are 6 to 7 mm in diameter, and the largest individual polyp is about 10 mm when fully expanded. Like most of the coral species we have spawned, baby Goniopora grow slowly until they are 3 to 5 months old, and then the growth increases dramatically.

We found significantly different growth rates in different systems. The growth of our baby Gonipora was considerably reduced in one system where the temperature was lower than 25° C (77° F) and little feeding occurred, when compared to another system where the temperature was about 25° C and regular feeding occurred. We believe an improved understanding of water conditions and food requirements, along with selecting growth as one of the major criteria for the next generation of broodstock, will improve growth rates dramatically in future generations of captive-bred Goniopora.

MP: Refining the cultural parameters to optimize baby coral growth will certainly require further investigation. What other unanswered questions do you have when it comes to breeding Goniopora corals, and what challenges will you have to overcome?

DG: Even though we have only been doing this for a few years, there was very little coral breeding information being shared at the time we started spawning coral. Now, there is a lot of information available.

Worse still, however, was the misinformation that was out there. For example, the ideas that coralline algae is required for coral to settle, or that the corals all spawn at the same time. This caused us to miss spawning events that happened early and to lose settled babies that were quickly overgrown by coralline algae.

Continued captive breeding efforts are going to identify bad information. For example, the scientific literature we have says that Goniopora corals are gonochoric spawners (that a coral is either male or female), but our corals spawned and released egg/sperm bundles, indicating that our Gonipora are hermaphroditic spawners.

It is easy to monitor branching corals like Acropora spp. for egg maturity by breaking off small tips. LPS corals are more difficult to monitor without killing the coral. This is particularly problematic with single polyp corals like Scolymias and Trachys. The result is that it’s harder to predict exactly when many of these corals will spawn.

MP: What benefits and opportunities are you seeing with captive-bred corals? Do you think they are going to be the “gold standard” in the aquarium trade?

DG: Both wild-caught and maricultured corals have already suffered setbacks from bleaching and pollution. If predictions are right, these coral sources will become riskier and more uncertain in the future. Asexually-produced corals are potentially disadvantaged by being clones, offering little opportunity to produce something different. Farming corals through fragmentation alone also requires a larger amount of broodstock colonies, compared to what you need to produce captive-bred corals. However, asexually propagated corals are able to reach marketable size faster than spawned corals.

This is truly the main challenge facing corals spawned in captivity—the time it takes from spawning to saleable size. This can currently range from 12 to 36 months depending on species. Apart from the cost of keeping the coral growing for that period, there is a lot of time for something to go wrong, like pump failures, disease outbeaks, and parasite infestations. However, as we learn more about coral growth requirements and by new brood stock selection, I am sure this time to market can be reduced.

Another big question is whether aquacultured corals will be more hardy than wild-collected corals, and generally easier to keep? While we’ve made leaps and bounds in terms of their husbandry, Goniopora can still be difficult to keep in aquaria. So it will be very interesting to see if captive-bred Goniopora, having spent their entire lives in captive conditions, are more resilient.

MP: I noticed in our early discussions you often refer to your sexually propagated corals as “spawned” vs. “captive-bred”. Is there a reason?

DG: This is all somewhat new in the aquarium trade. Under the CITES definition, “captive-bred” also refers to frags grown from frags which is why I often say “spawned”. That said, I believe most of your readers will understand “captive-bred” as originating from sexual propagation. Perhaps we’ll have to say “captive-spawned” or “spawned in captivity”?

MP: What’s next? What does your company aspire to accomplish? What is it going to take to get you to your goals?

DG: Spawning to date has been a mix of facility-held broodstock and freshly-collected wild broodstock. We intend to consolidate our existing work, so we can consistently spawn corals from facility-held broodstock and not rely on wild-collected coral. We absolutely want to add more species to our list of spawned corals. We are currently conducting trials to manipulate corals to spawn out of season (as per Jamie Craggs) to more evenly distribute the workload over the season.

MP: We’re all aware that Australia is imposing ever-stricter quotas on wild coral collection and exportation. How does trade in captive-bred corals relate to collection/export laws and restrictions?

DG: According to CITES definition, captive-bred corals are corals raised from parents bred in a captive environment, so all our corals spawned from wild-collected corals come under the heading of “farmed”. There is a very small chance some of our three-year-old corals may spawn this year, but it is more likely the following year. Australia’s wildlife export laws currently allow export of captive-bred corals but not farmed corals. The EPBC Act (Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999) is currently being reviewed, and farmed corals have been proposed as an amendment to be allowed for export. As with all government legislation, there is no indication of how long this will take.

MP: So where can people get your captive-bred corals at this time?

DG: We have over 500 captive-bred corals ready for sale (approximately frag size) and are contemplating doing a release in the Australian aquarium market later this year. If losses are kept at a minimum, we hope to have thousands of captive-bred corals available the following year. Hopefully, the new Australian legislation will be in place by then and we can export, giving our existing wholesale customers the first opportunity for distribution. A premium on price for captive-bred corals would be nice, and could further our research, but ultimately the market will set the price for our captive-bred corals.

I am immensely proud of the achievements of the Inter-Fish team. The captive breeding of Goniopora and other coral species will help to reduce pressure on wild populations and ensure that these beautiful and important organisms are available for future generations to enjoy.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks