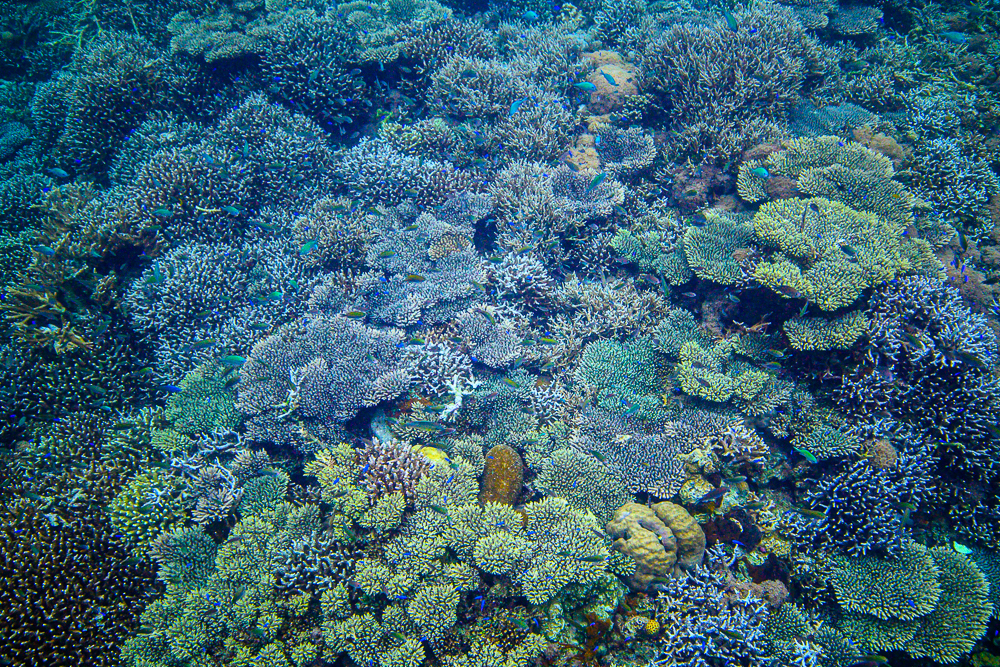

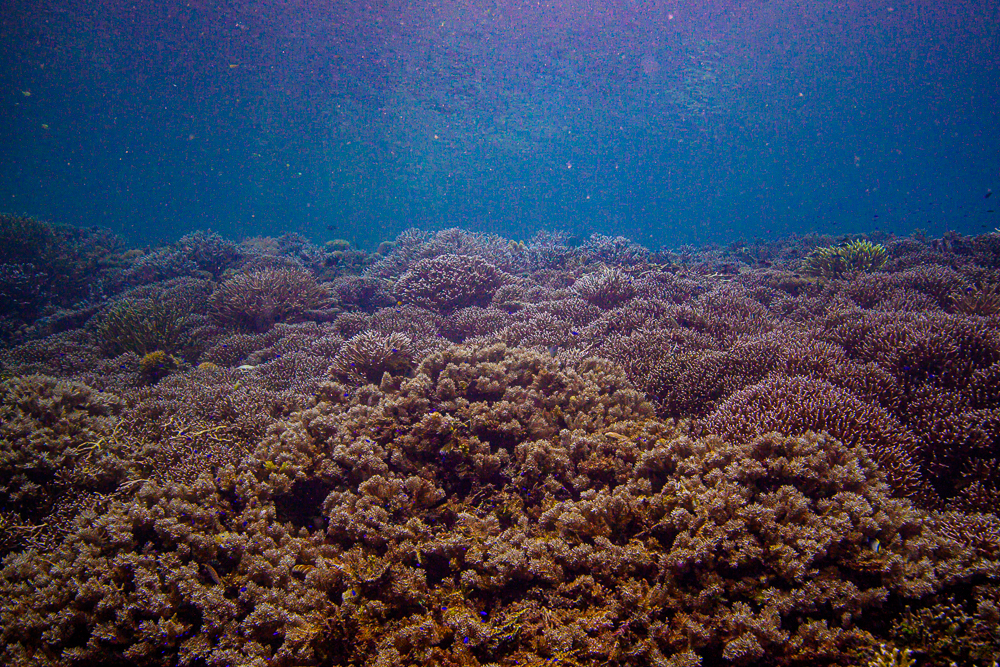

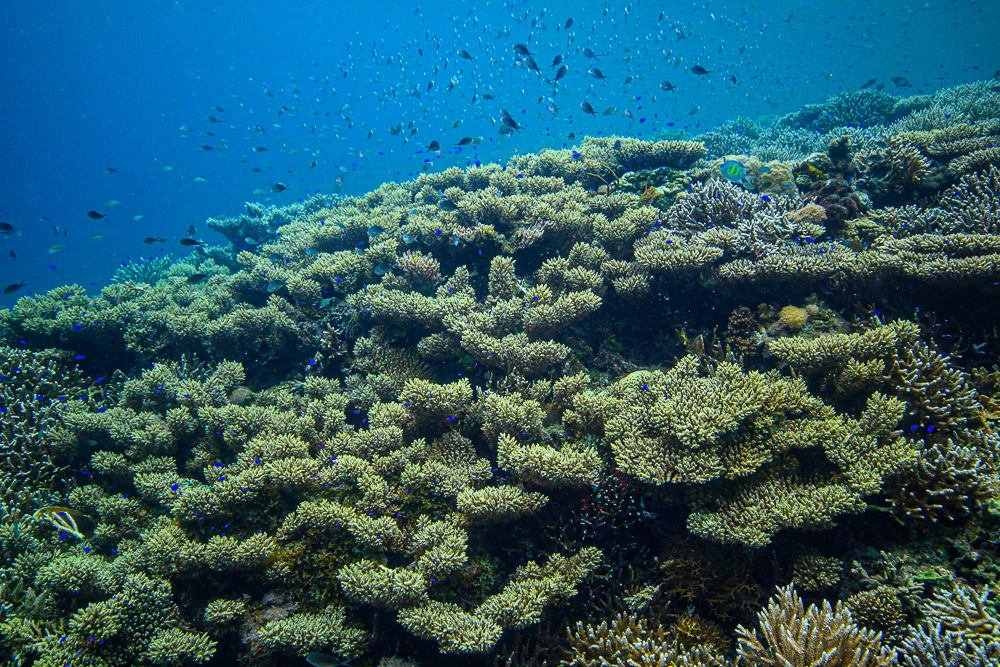

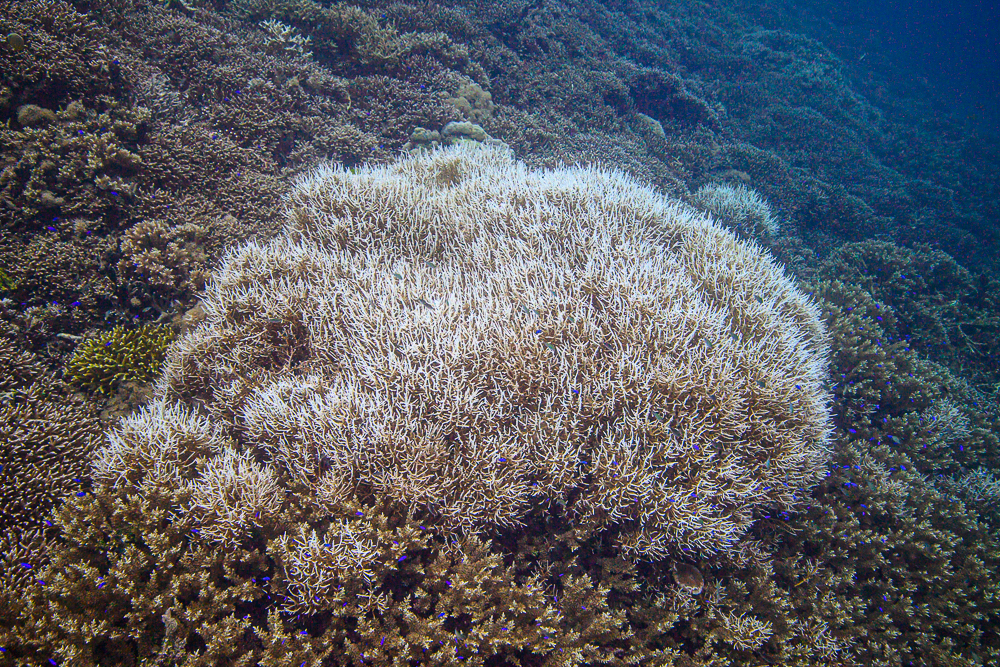

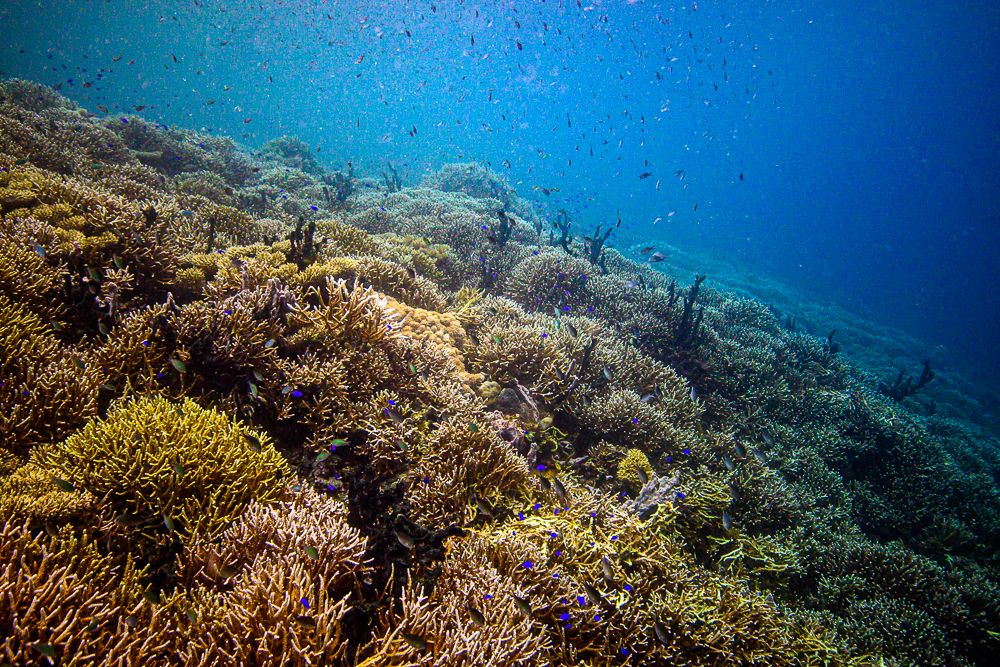

Traveling and diving around Indonesia, I recently came upon a very interesting and healthy coral garden, within the vicinity of a submerged hot water spring. Hydrothermal springs are a very common occurrence around Indonesia, as the archipelago is sitting on the “Ring of Fire” and is speckled with active volcanoes.

According to Wikipedia, these hot springs are created when “groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circulation through faults to hot rock deep in the Earth’s crust. In either case, the ultimate source of the heat is radioactive decay of naturally occurring radioactive elements in the Earth’s mantle, the layer beneath the crust.” As the water heats up, it also dissolves minerals, heavy metals, and other trace elements.

Abnormally Warm Waters:

On a snorkeling trip along the west coast of Halmahera, the main island of the Maluku Islands in the North Maluku province of Indonesia, we came upon a nice protected bay. It isn’t known for saltwater crocodiles. The hot water springs bring villagers and a few tourists that are up for a hot seawater bath. Given this human activity, the area is kept free of Saltwater Crocodiles.

The hot water spring is located just on the edge of a rock, a couple of feet deep. The surface water in the vicinity was so hot that you couldn’t get too close. And 10 meters (30 feet) away from the hydrothermal vent, you could clearly feel that the first couple of feet of water were a lot warmer than the deeper layer of water underneath.

Since the reef flat was only 1 meter (3 feet) deep, we assume that corals could directly feel the warm water, and sometimes be bathed in it at low tide.

No Bleached Corals Here!

Unfortunately, it’s hard to travel in these areas with a huge quantity of equipment. So I didn’t bring a pH meter, as it would have been very interesting to know the basic chemistry of the hot water spring and surrounding seawater pH.

However, my dive computer recorded a maximum water temperature of 35C (95F), with an average water temperature of 32C (89.6 F). Other spots in the area were at 29.5C (85F). It is important to note that most other sites in the area included corals that were showing mild bleaching signs, while the location in the direct vicinity of the hot spring had none.

Could understanding the trace elements from these hydrothermal vents bring us the ultimate coral reef?

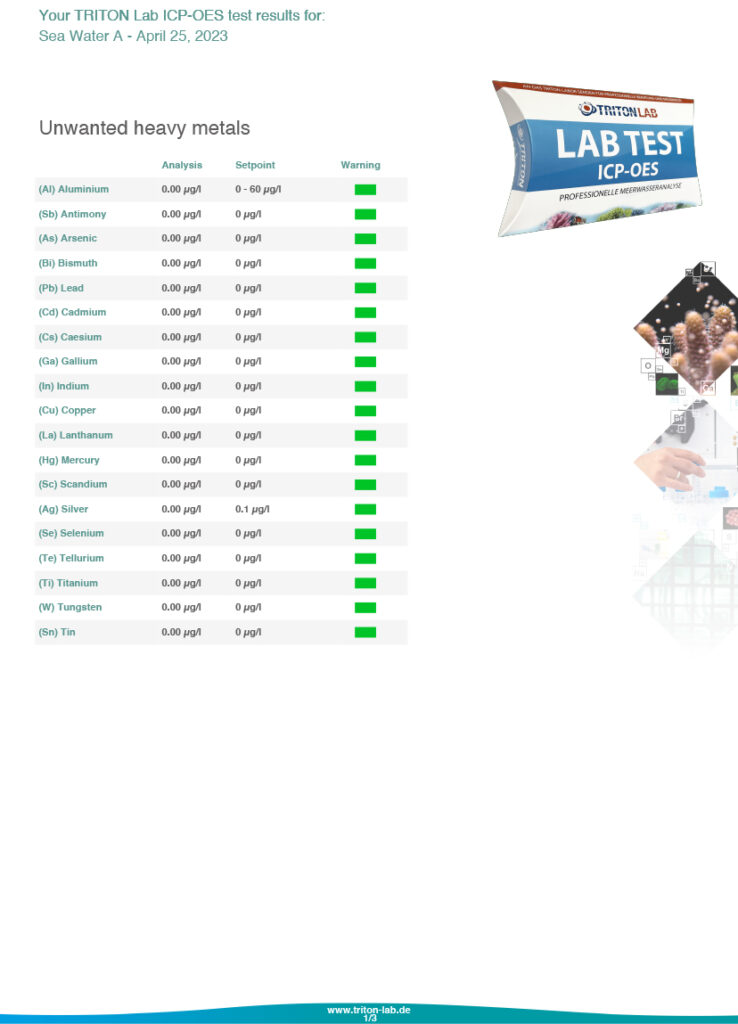

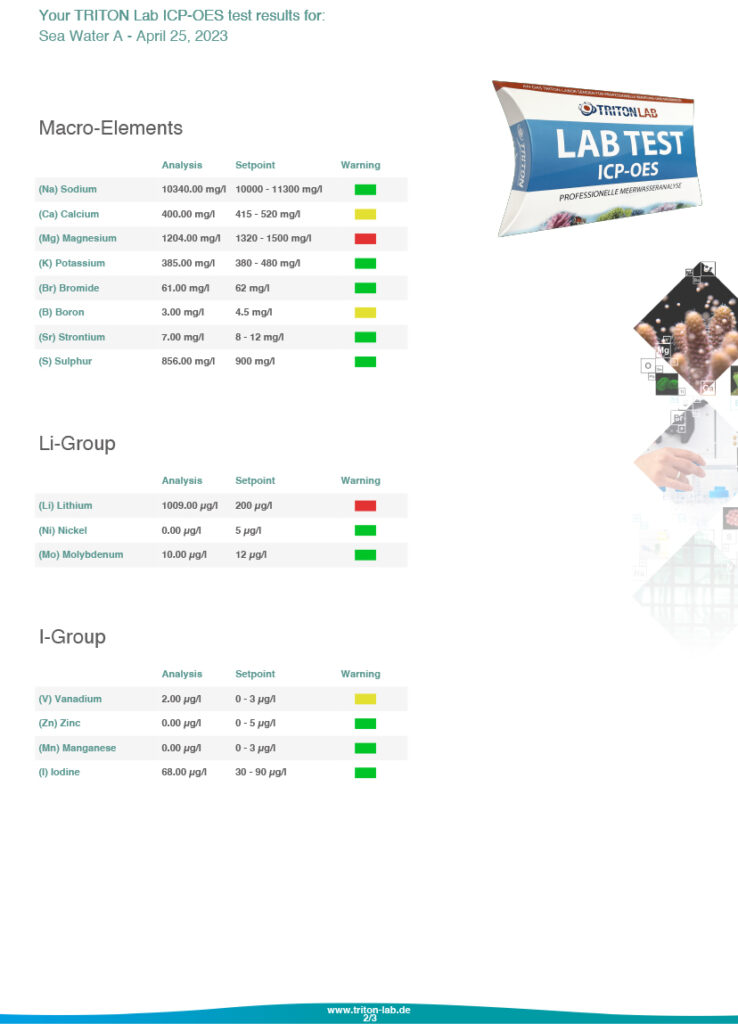

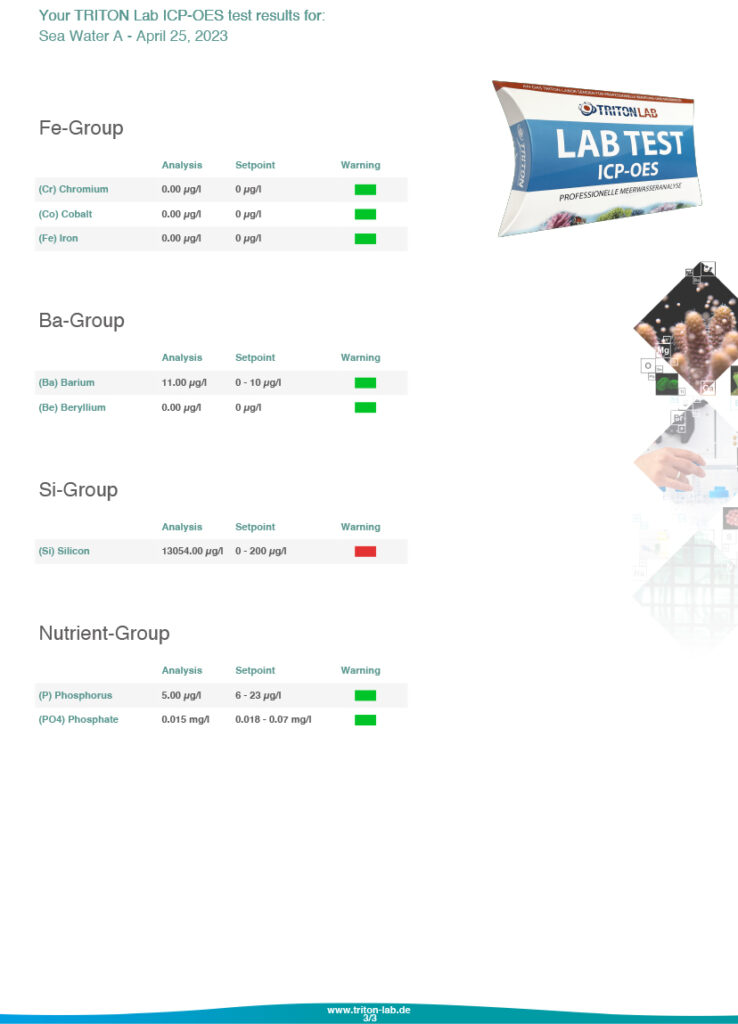

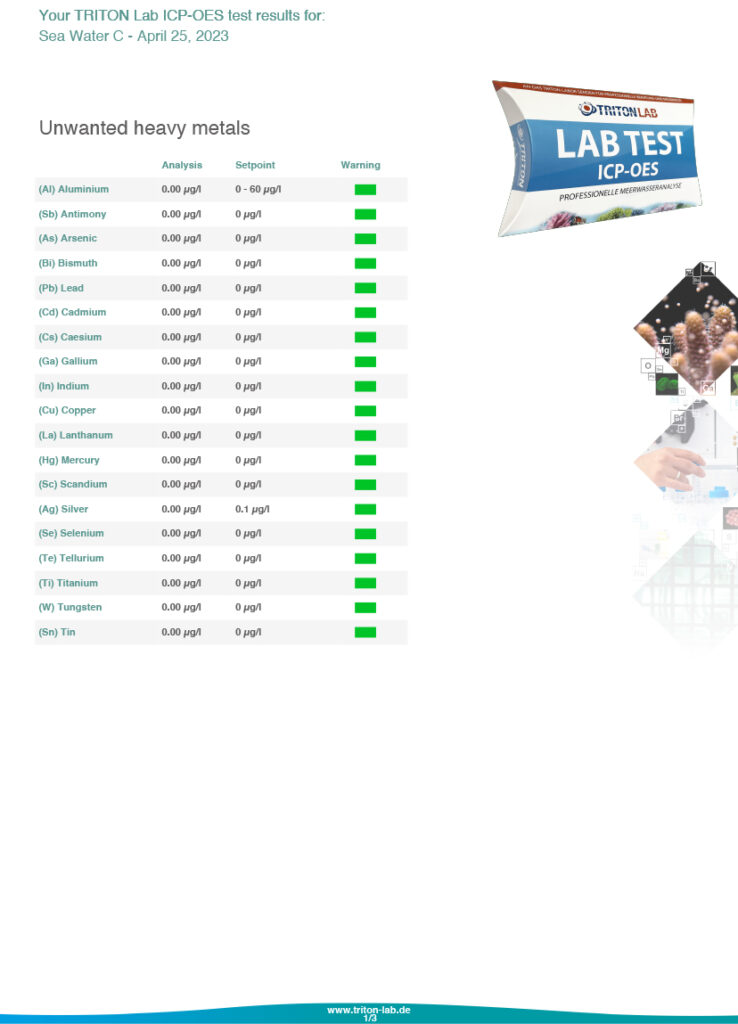

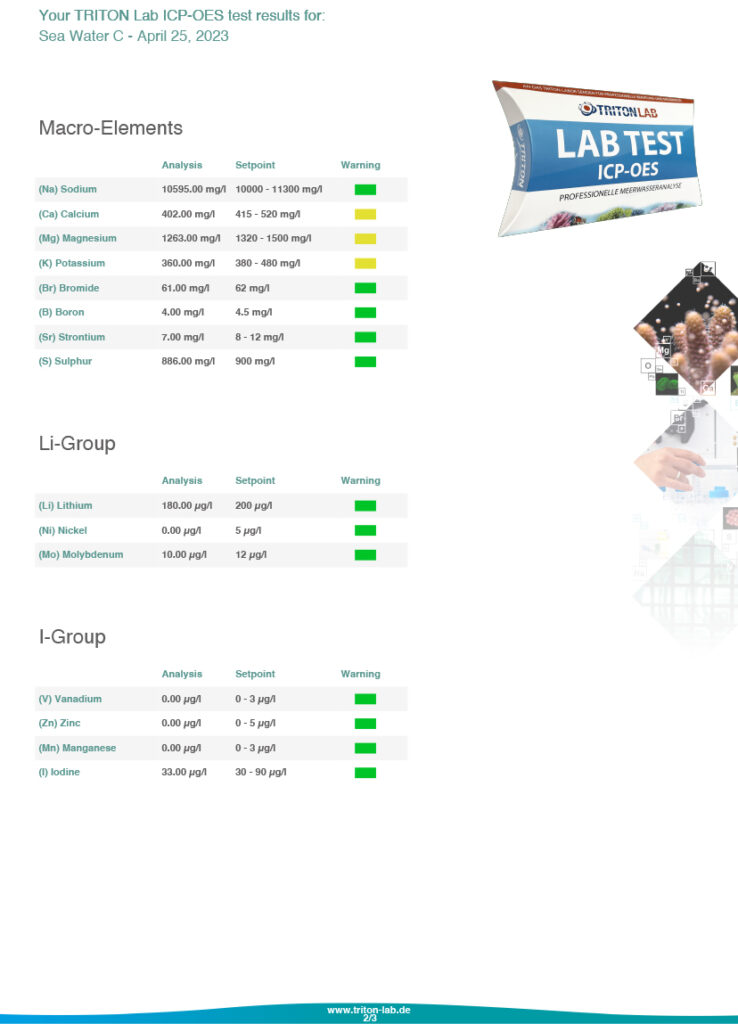

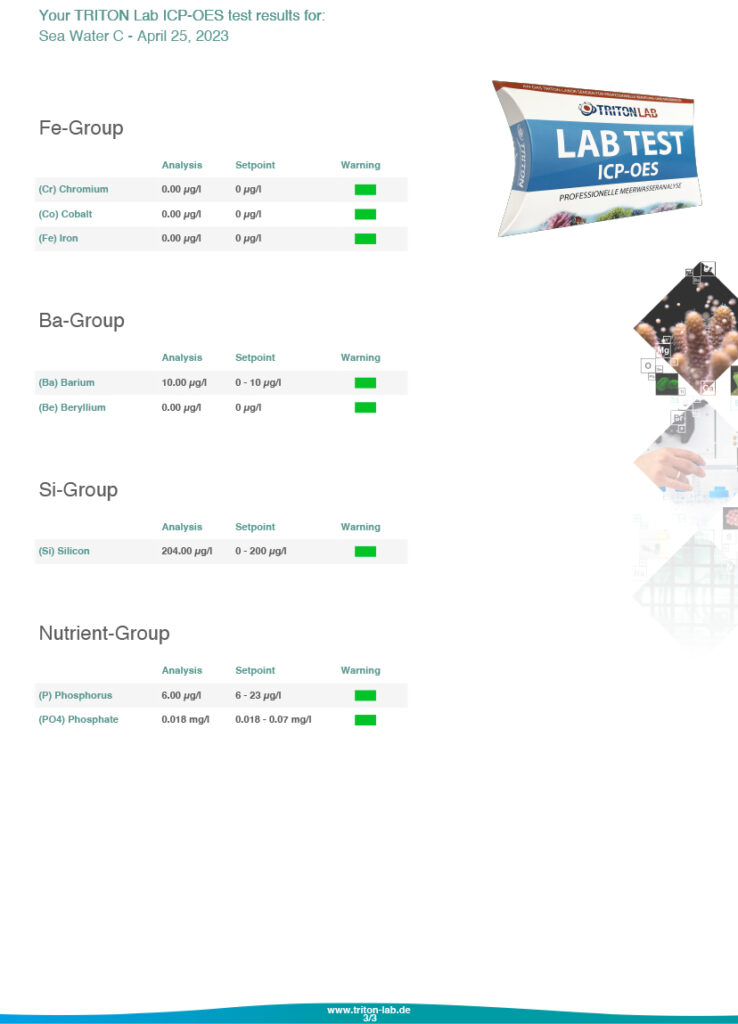

Having access to Triton ICP Labs, I couldn’t resist taking some water samples to be sent to the lab in Germany, and the results came back with quite a few interesting readings. I took a sample directly outside the vent, as close as I could get without burning myself. Then a second sample was taken at 1 m (3ft) deep on an Acropora tenuis bed, 5 m (15ft) from the vent. And finally, a third sample was taken on top of the slope, 4 m (12ft) deep, 10 m (30ft) from the vent.

Silicate was through the roof in the ICP results. Not only was it high directly in the vent, but also still very high on the reef below. Silicate is consumed rapidly by phytoplankton such as diatoms. Being the foundation of the food chain, it is possible that this abundance of silicate might create a large availability of food that is directly feeding the corals and helping them to cope with difficult environmental conditions. Lithium was also very high, which is not surprising since lithium mines are popping up everywhere in Halmahera to source the raw materials needed for the batteries in electric vehicles. Note that the damage to the environment and reefs that is caused by the mines is enormous.

Some trace elements are slightly off:

I asked Ehsan Dashti, the founder of Triton Labs and first to use ICP-OES for reef aquarium water testing, what he thought about these results, and here is what came out of the discussion:

The main elevated values are silicon and lithium which have not been proven beneficial for corals yet. However, they could have effects on the coral environment in a positive way depending on elements’ form.

For example, we have seen lithium inhibiting Bryopsis algae growth in aquariums. Bryopsis is a direct competitor with both captive corals and in nature, so perhaps elevated lithium levels could be reducing passive stress on corals by inhibiting the growth of competitive algae.

Silicon itself? Ehsan looks at it more negatively, but the form it is in would be an important consideration. An ICP test can only identify the atom itself, but not in which molecule it was bound before. More scientific work would be helpful and needs to be performed. The discovery of a beneficial form of Si would be very interesting.

Taking a deeper look at the samples, Ehsan notes that iodine and vanadium look more stable. They are normally very volatile and disappear quickly. But both are known to be very positive for sponges, coral growth, and coloration.

The amounts of iodine and vanadium are not overwhelmingly high like the other elements mentioned but could be bound in molecules that are more bioavailable for corals. So, hypothetically, their impact might be stronger, and the element is available to the corals for a longer timeframe.

As soon as we venture outwards on the reef, these elevated levels are quickly diluted. Could they be the reason why the coral reef directly in the vicinity of this warm-water vent is healthy and showing no bleaching even though the water is warmer than its surroundings? This is a particularly interesting question to pose, given that we can see evidence of stress with partially bleached corals nearby. We really must go back to learn more…