Matt Pedersen talks with JAKE ADAMS

A full excerpt from the CORAL Magazine, Volume 11, Issue 2, March/April 2014.

You may have seen the INSTAFLOW advertisements out there; this is arguably the marine aquarium trade’s most successful inside-joke-gone-mainstream. It’s the brainchild of Richard Ross (Steinhart Aquarium) and Gresham Hendee (Reed Mariculture) and was inspired by Brian Edwards (Fins Reef), who said that Jake thinks “flow is more important than water.” INSTAFLOW is a not-so-subtle parody on the claims made for some very real aquarium products that have appeared in the market over the years. Art imitates life, and there’s a tendency to tease those we hold most dear. Within the playful minds of Hendee and Ross must certainly exist a deep appreciation and respect for Jake Adams and his obsession with aquarium water flow and circulation.

These days, most readers probably know Adams for his role as the face of ReefBuilders.com, where he is the editor and the most prolific contributor. He is a man with his finger on the product pulse of the marine aquarium industry, but you might not be aware that in his truly defining moments, he talks about things like coral respiration, tank gyres, and fluid momentum. I sat down with Adams in late January 2014 at my home in Duluth, Minnesota, to revisit his insights on water flow in the reef aquarium…but not before he changed the position of a circulation pump in my fishroom saltwater pond so it would “perform better”!

Jake, I know you as Mr. INSTAFLOW. When is that product coming out?

Heh heh…it’s still in development.

So, in all seriousness, you’ve said water flow is more important than light.

Mmm hmmmm….

And it’s more important than water.

I joke that it’s more important than water.

So start from the top.

When I was in college I had the opportunity to do a research project. I took a look around to see what people were working on. Light is sexy. Sanjay [Joshi] had that down. Dana Riddle had that down. Everybody was trying to be the lighting expert. I liked the flow aspect, so I just started working at it.

We were in the dark ages back then. People would talk about turnover rates in their tanks—x-times turnover rate per hour. Back then it was all system pumps and powerheads. We didn’t have prop pumps to just move water—to move a lot of water.

I want to go all the way back to the coral research that you did, looking at flow rate and its effect on coral respiration. Please bring that back to the forefront, because I think that information has kind of been buried.

A coral is a very passive organism; it’s very much at the mercy of its environment and the elements. It’s dependent on the light to hit it where it is, and the flow to come to it where it is. That means we have to drive the system around for the coral. I was looking at the effect of water flow on respiration and photosynthesis, breathing and making energy. [A lot of] my research was really figuring out how to do the research.

What were you doing?

I was measuring the change in oxygen levels when applying various levels of unidirectional flow [in a contained sample of water with various small Pocillopora coral colonies]. The linchpin of the research was having a fiber optic sensor that was sensitive enough to measure minute changes in oxygen levels. So if the O2 level drops, that’s oxygen consumption; if it stays the same there’s a balance between respiration and photosynthesis; if it rises, that’s photosynthetic output. I was looking at how these changes in O2 level occurred under a few different flow speeds, and it was quite fascinating.

What were some of your conclusions?

More flow is always better. It’s always better for breathing, and it’s always better for photosynthesis—up to a point. If you’re blasting tissue off, then it’s a point of huge concern. Flow speed at the coral colony itself is what matters.

You talk about laminar flow. One of the things I remember you bringing up is the coral itself…

You haven’t finished the question yet, but I know the answer. So ever since the beginning, it’s been all about random, chaotic, turbulent water flow—that’s where the gas or nutrient exchange takes place. What people don’t understand is that turbulence only needs to happen at the site of the coral, right where the water hits the coral. We’re talking about a microns-thick layer of water around the coral. It doesn’t have to happen in the open water.

The best way to [have turbulent flow at the site of the coral] is to have faster water. It’s just like driving a car and crashing into a tree at 15 miles per hour: you’ll be walking away because you don’t experience much turbulence. You hit that same tree at 60 miles per hour? You’re going to need an ambulance.

So the old-school idea of pointing two powerheads at each another and blasting away is wrong?

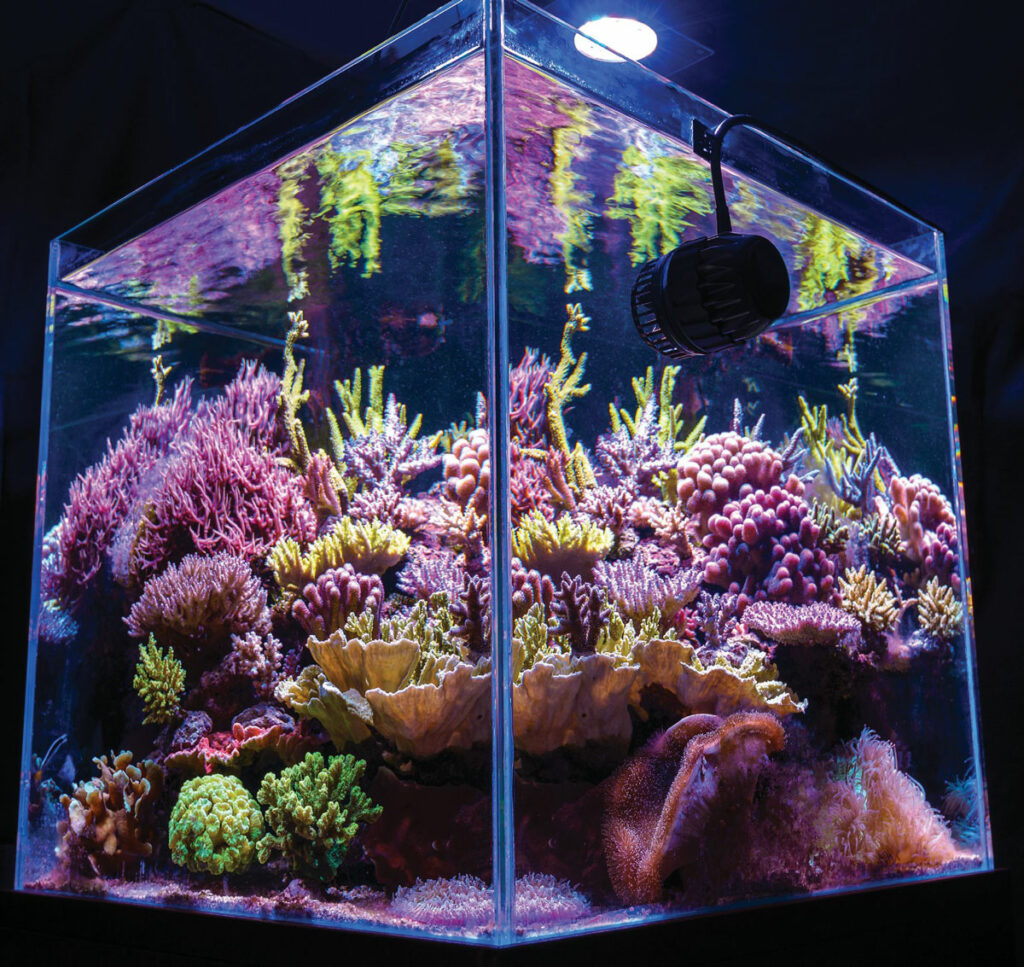

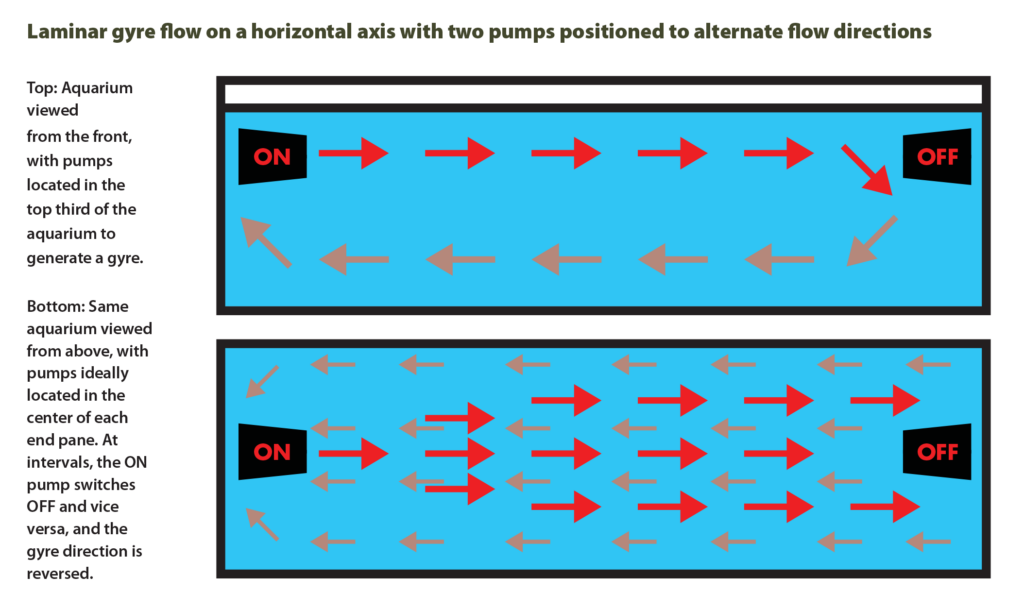

It’s not wrong…it’s misguided. The reason I focus on laminar (unidirectional) flow is because you can architect that into a gyre, into a loop—a conveyor belt of water moving inside your tank. When you do that you’re building momentum, and you’re efficiently moving the entire mass of water. Whatever equipment you are using—powerhead, closed loop, return pump, propeller pump—you get more flow speed out of it. That’s why I stress having laminar, gyre flow.

If you have an infinite amount of power and powerheads, yeah baby— let it go crazy. But when you have laminar flow, the flow is homogenized from one place to the other, so you can put corals in different places and reliably predict what kind of flow those corals will experience.

How do you set up your ultra-simple Jake Adams gyreflow system?

Without any divider (which would physically turn the aquarium into a racetrack), you just move a cross-section of the surface of the water. If you have a typical rectangular tank, somewhat elongated, you can move one-third of the cross-section of that surface water and it’s going to propagate. It’s going to move all the way across the tank. It’s going to build up on the other side, and it’s going to fall, and it’s going to come back. So you don’t need to worry what’s happening 4 feet down in the tank if you just focus on that cross-section. How would you set up a typical rectangular tank for the simplest, most basic, most efficient flow? Start with a good propeller pump at each end of the tank, large enough to move that one-third cross-section of water from one end to the other. You move it for a period of time, because a gyre builds up and the water as a whole picks up momentum. This creates “Mass Water Movement”; all of the water in the aquarium moves together as one cohesive unit.

So, maybe you put a pump in the top right corner, blowing across the front of the tank to the left?

No, you put it in the center. Always try to center the pump (front to back) and always try to get it toward the top. [As Adams often explains, surface water encounters the least resistance, and its momentum helps pull lower waters along for the ride.]

And experiment. I always tell people in my talks, “Don’t take my guidelines too literally. Use them as tools, and then experiment.” If you have one pump for each end of the aquarium, you put each one right in the center of the end (front to back) and at the one-third depth to move as much of the cross-section as possible. If you have four pumps, you put one at the one-third mark and one at the two-thirds mark (front to back) at each end to move as much of those cross-sections as possible. In a nano tank, you’re looking at only a couple of minutes to get that gyre started. It really only takes up to 15 minutes in some of the biggest tanks for that gyre, that momentum, to build up to maximum speed.

There’s no reason to change the direction of the gyre, to alternate it, as fast as you can. Let it flow in one direction for 20 minutes, 30 minutes, longer. Somewhere between an hour and three hours (maximum) is my cutoff mark between the two directions. That said, I sometimes tell new hobbyists to just keep the flow going in the same direction all the time. Once the corals grow, they might look a little windswept and a little weird, right? But I’d rather have them do it right than trip themselves up.

Before they get to “windswept corals,” do you tell them to flip the current in the other direction?

In an ideal world, yes. Sometimes, depending on who I’m talking to, I just tell them to get their powerheads working together, so they can get that laminar flow going in one direction until they’re able to afford a couple more pumps, and that timer or controller, to alternate. One thing people don’t realize is that all the turbulence that happens when a fluid hits an object happens on the backside. So it’s the backside of the coral (from the direction of the flow) that is going to experience that actual random, chaotic mixing that they need. So that’s the reason, ultimately, to have alternating flow.

So they don’t get windswept corals!

Windswept corals that are growing well look a lot better than symmetrical corals that are having lots of issues, know what I mean?

Sure. Tell me a little bit about the state of fluid dynamics in the reef hobby—what you see now, and what we’ll be seeing next.

A lot of people have gotten the message that we need water flow, but they haven’t gotten the full message about the techniques for achieving it. More laminar flow—the gyre method of building momentum—that’s what people still need to hear. And, particularly in America (I travel around a bit), where more is always better, instead of being smarter about our flow we’ve just done more. A lot of the tanks I see that are “well flowed” could probably have half as much equipment and a third of the water return outlets. You know, I see a lot of people get crazy with their closed-loop outlets, and it looks like a battleship, basically, except all the stuff is pointed inward.

So we’re doing well as far as increasing the amount of flow we’re putting into our tanks, but we have room to improve in terms of how we deliver that water flow.

And that’s in both efficiency and equipment?

It’s just that people, instead of being smart with two pumps, they get four pumps and have that much more flow going on.

Let’s talk about equipment: what you like, what don’t you like, what’s bringing it to the table, what’s letting people down?

I’m sticking with propeller pumps for the moment. On the flow-per-dollar side of things, the Hydor Koralia pumps are great and they’re really making it easy for the hobbyist to just set up a tank, pick up a pair of circulation pumps, and go. But if you want shear flow-rate-per-dollar, the Sicce Voyager HPs are just killer—they put out so much force. They’re not small pumps, they’re a little blocky, but they’re super silent and they push a ton of water. And Tunze makes some really pragmatic pumps, and their Turbelle Nanostreams and the new electronic Nanostreams are some of the pumps to beat. When it comes to controllable pumps, the king of the mountain at the moment is the VorTech pump. It’s not for every tank, because you have to put the motor on the outside of the tank. The VorTech pumps have had a lot of programming, a lot of features, but they’ve been stuck on one program setting until now.

Conditions change throughout the day, at night, and when you feed. So this year, I’m really looking forward to controlling my pumps using third-party hardware and software—hooking them up to something like an Apex AquaController or the ReefLink by EcoTech (maker of the VorTech line). Instead of having one program (flow pattern) throughout the day, which was a lot better than what we had, now we can have different programs.

Why does this matter? For example, look at coral feeding. Particle capture rate is related to flow speed—how much water can get past those polyps in a certain amount of time. So what I’m looking forward to doing in the near future is actually having programmable pumps that behave in specific ways when I automatically dose the tank. So my feeding mode might actually increase laminar flow in the tank [to better facilitate coral feeding].

Getting back to setting up your tank for flow, what tips do you have?

Nothing makes me want to cry harder than when people say they can’t turn up their pumps because it will blow their sand around. Where most of our corals are harvested, where corals are found in abundance and diversity, there is no sand. There may be a little sand in pockets, but there’s no sand bed like in people’s fish tanks.

Are you talking mainly about reef-building SPS type corals?

I’m talking about everything.

LPSs?

Well, of course you know Scolymias are found in mud. But even Fungia—you think of it living on sand, but Fungia doesn’t believe in sand. If it lived on sand it’d be buried all the time; it lives on a rock! It lives at angles, in colonies, on rubble. So my favorite substrate for high-flow tanks is actually calcium reactor media…such as the “coral bones” in Two Little Fishies’ ReBorn media.

Or no substrate at all?

Or no substrate at all. Or a solid substrate with tiles or limestone. But the point is, take your water flow into account when you design your tank. That means being mindful of what substrate you use and how much. That also means being mindful about how much rock you put in the tank, right? Because if you put a ton of rock in your tank, you won’t have that much room for coral, and it’s also going to slow down your water flow. So it’s critical to think about how the water is going to move in your tank. The flow, not the light, is driving the respiration of the corals. People spend a lot of time on the light, but not on the flow.

How do you measure flow? What’s the metric you can use to make determinations?

Part of the reason I push for laminar flow is because you can measure it. If you have random, chaotic flow it’s just not going to be practical to measure.

When you have unidirectional laminar flow, it’s just a matter of putting flake food or some semi-buoyant material on one side of the tank and watching it move across to the other side in a large tank. You time how long it takes for that particle to move X feet and you can determine its speed in feet per second or inches per second. I use centimeters per second because that’s what’s out there. So 20 cm per second is about 8 inches per second, and that’s a really good metric for a healthy reef. If you need more precise measurements, or you have a smaller tank, you can actually tape a plastic ruler to your tank and use a video camera to record the particle moving. Then you just need to examine the video frame by frame to measure distance, and you know each frame corresponds to a certain fraction of a second.

So I want to jump to the side: waveboxes, wave motion— what’s your thought on those?

Waveboxes are really cool, and that goes back to what I was saying about having different water flow modes that are more [customized to] the needs of the coral and the peculiarities of the flow.

I have a gorgonian tank that’s on a permanent wave. It’s really beautiful, and the gorgonians move back and forth. But that is the worst kind of flow that I could have for them to capture a ton of particles. When water moves back and forth, or oscillates, it doesn’t travel anywhere. It just moves back and forth.

That being said, there’s a really big difference between the Tunze Wavebox, which really just makes a standing wave, and the VorTech pump, which makes a pulse. That pulse has a traveling component within it; it’s laminar, so it goes, it stops, goes, stops, goes, stops.

My gorgonian tank is on a permanent wave, which is great for turbulent gas exchange, but it doesn’t really travel that far. I have an automatic feeder on that tank. I use Crossover Diet (from Neptune Systems and Reed Mariculture), so ideally, when the food goes in, the pump would switch over to ON mode, which would create a gyre, which would pass a ton of particles by all the tentacles and keep the food in suspension for about 20–30 minutes. Then the VorTech would revert back to the wave action. Waves are cool, and they’re pretty. They dislodge detritus, but they don’t carry it away.

In a perfect world, you’d alternate between oscillatory flow, then laminar flow, then back to oscillatory flow, and then laminar flow in the other direction, and then start the cycle over. To me, that is the gold standard, the combination of transporting gases, particles, and particulate waste (using a laminar gyre flow) and dislodging particulate waste with oscillating flow.

What else can benefit from flow?

Flow is really cool for fish; it stimulates them. People don’t want boring, fat fish sitting around looking at you getting fat in the tail. My fish get a lot of flow—they get a washing machine of flow. What’s really cool is that they’re super active, they’re fat and fit, they’re thick, and they’re just really alert and stimulated. There’s a Sicce Voyager HP4000 on one side of my 150-gallon (568-L), 6-foot (1.8-m) long fish tank; it moves. My 8-inch (20-cm), really old Regal Blue Tang, he’ll just ride the current for a long time.

So he’ll just kinda coast…

No, he’s gotta go—he’s gotta run across it.

Like he’s on a treadmill?

Yeah. You know, the argument could be made that if you take a fish out of the ocean and put ’im into a box, that’s not fair. But if they have a treadmill they can get on, all of a sudden that aquarium has infinite size. That’s oversimplifying the issue, because the fish can’t swim wherever it wants. But, man, when I turn the flow off in that tank, the fish are still swimming all over the place as if there was still water flow. It might take them an hour to settle down.

You do a lot of diving. What does the flow feel like on the typical reef? Can you describe what you experience on a reef, what the fish are experiencing on the reef?

There are certain places where it feels like the ocean is telling you to “GET OUT.” There’s so much flow, you feel like Mother Earth is telling you, “YOU DON’T BELONG HERE.” Any place you can have really luxurious coral growth, that’s where you have a lot of water flow, and that’s often where you feel like you shouldn’t be there. Other places have tidal alternation, so at times the current is really unidirectional, it’s really ripping, and other times it’s kind of a slack tide and kind of chilled out. There are some places where it’s unbelievable how much flow there is. I went to a spot I call Hidden Reef in Mauritius this summer. It was wintertime there, so the seas were a little choppy, and it was so hard to swim. Yet you wouldn’t believe the corals that were growing there in this crazy strong water flow; things you wouldn’t think could live there. There were lots of softies, Psammocora, and all these things that you’d consider to be lower- or middle-energy corals—there was huge diversity in this reef. There were Pavona holding on for dear life in 3 or 4 feet of water, and by holding on, I mean they’re huge, super-thick colonies—maybe I was the one holding on for dear life.

It just comes back full circle to getting away from flow (turnover) rates, getting away from certain metrics, getting away from hitting that one coral with that jet stream. What’s really different about the ocean is that most of the water is moving together; it’s Mass Water Movement. Stop thinking about jets in your tank—how do you move the whole thing at once? That’s the real difference.

What life in our tanks can really be harmed by flow?

Euphyllias don’t like a lot of flow. They live in sheltered areas. They can adapt to flow, but the corals will never be as plush and rich. I have some in my SPS tank. My SPS tank might grow Euphyllia a little faster, but it also grows thinner and the polyps don’t fill in to hide the skeleton underneath. Euphyllia—keep it on the down-low. Scolymias, Blastomussas, and Lobophyllias are similar. Chalices just don’t need that much flow. ’Shrooms won’t open up the same way under strong flow—they love that light flow. They can also open up real big, or get real small if the light is too bright. On the flipside, some of the corals that are really getting under-flowed are soft corals. I don’t know how we succeeded with soft corals back in the day, but the more I tried to keep them the way I thought we kept them, the more I failed. The more I treat them like stony corals, the better I do. I’m starting to give Sarcophytons, Neptheas, Lobophytums—things like that—much more generous flow.

![The system of the future [in 2014], in which lighting and current-producing pumps work in sync to produce more realistic variations on daily and seasonal cycles. This tank features Radion LED lights and VorTech pumps controlled electronically by a ReefLink computer system, all by EcoTech Marine.](https://www.coralmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Jake-Adams-Interview-from-CORAL_Magazine_MarApr_2014-175-1024x683.jpg)

Any final thoughts, Jake?

My parting note to everybody is to observe your tank. Watch what it’s doing. Forget the rules for a second, forget what you think you know, and just watch. Move your pump around and use some critical analysis to evaluate the water flow.

On The Internet

Adams, Jake. 2006. “Water flow is more important for corals than light. Part 1. Introduction to gas exchange.” http://www. advancedaquarist.com/2006/6/aafeature2

———. 2006. “Water flow is more important for corals than light. Part II: The science of corals and water flow.” http://www. advancedaquarist.com/2006/8/aafeature

———. 2006. “Water flow is more important for corals than light. Part III.” http://www.advancedaquarist.com/2006/9/aafeature2

———. 2006. “Water flow is more important for corals than light. Part 4: Basics of hydrodynamics.” http://www. advancedaquarist.com/2006/11/aafeature

———. 2007. “Water flow is more important for corals than light. Part V.” http://www. advancedaquarist.com/2007/1/aafeature

———. 2009. “INSTAFLOW will make your corals from Tonga.” http://reefbuilders.com/2009/04/01/instaflow-corals-tonga/

———. 2010. “Product Review: Reefing Like It’s 1999: How Reef Aquarium Flow and Lighting Has Changed over the Past Decade.” http://www.advancedaquarist.com/2010/1/review2

Ross, Richard. “Skeptical Reefkeeping, Part 2: Magic in a Bottle.” http://www.reefs.com/forum/reefs-magazine/82364-skepticalreefkeeping- part-2-magic-bottle-richard-ross.html