As ocean temperatures rise, pistol shrimp sound a warning

August 18, 2022

via: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

In a warming ocean, snapping shrimp might be the acoustic canary in the coal mine.

Research published by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) scientists in Frontiers in Marine Science confirmed their previous observations that rising temperatures increase the sound of snapping shrimp, a tiny crustacean found in temperate and tropical coastal marine environments around the world.

In the first study of its kind, WHOI marine ecologists Ashlee Lillis, Ph.D. and Prof. Aran Mooney, Ph.D. established a clear relationship between rising temperatures and the frequency and volume of the sound emitted by two snapping shrimp species, with implications for underwater navigation and communication for both humans and animals. The continuous popping sounds made by snapping shrimp—which evoke the sound of sizzling bacon—are so loud and cover such a wide acoustic range that it can interfere with ship sonar and fish finders. Research shows that whales and dolphins may rely on the sound of snapping shrimp to orient themselves along the coast, and diverse soundscapes help attract fish, shellfish, and coral larvae to appropriate settling sites.

“These shrimp are the most ubiquitous sound producer in the ocean, and now we have evidence that temperature has a huge impact on their behavior and the overall soundscape,” said Dr. Lillis, a WHOI guest investigator and principle scientist at Sound Ocean Science. “That’s relevant to everything from migrating whales to larvae trying to use the soundscape, or humans who use the sea for extractive or military purposes.”

Lillis analyzed recordings of snapping shrimp from an oyster reef off the North Carolina coast and found an increase of 1 to 2 decibels, as well as a 15 to 60 percent increase in snapping frequency, for every Celsius degree rise in temperature. Put to the test in controlled lab setting, Lillis found that snap frequency more than doubled with water temperatures between 68F (20C) and 86F (30C), with some differences depending on the season or the shrimps’ social grouping.

A second larger experiment was conducted with 60 individual shrimp (42 Alpheus heterochaelis, 18 A. angulosus) and 54 pairs of shrimp (36 pairs of A. heterochaelis, 18 pairs of A. angulosus) testing the effect of water temperatures of 10°C, 20°C, and 30°C.

The experiments simulated the effects of a short-term heat wave, so it’s not yet clear whether the shrimp might eventually adapt, or how the increased snapping could impact their physiology or the ecosystem over time. While temperature has long been understood to influence crustacean behavior, the effects of warming water on the overall marine soundscape is a crucial—and often overlooked—ramification of climate change, says Mooney.

“Climate change is impacting the marine soundscape in fundamental ways,” Mooney said. “Warming waters can influence how animals are physically able to communicate and use sound to reproduce and attract mates. We don’t yet know what happens to the ecosystem when background noise levels are higher, but there are far-reaching implications.”

Funding for this research was provided by NSF Biological Oceanography Grant #1536782 and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Interdisciplinary Award and Postdoctoral Scholar Programs.

Story Source:

—Materials provided by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Journal Reference:

Ashlee Lillis, T. Aran Mooney. Sounds of a changing sea: Temperature drives acoustic output by dominant biological sound-producers in shallow water habitats. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2022; 9 DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2022.960881

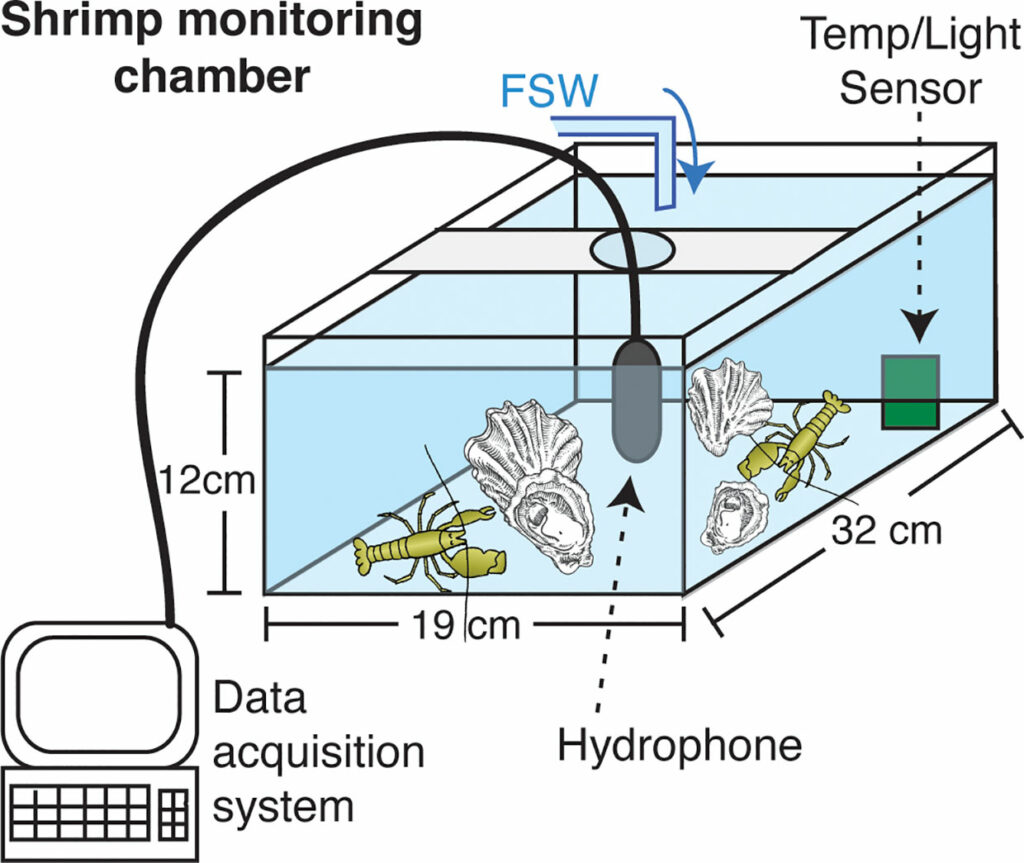

FIGURE 1 Experimental chamber set-up for acoustic monitoring of snapping shrimp under different temperature treatments. Schematic shows example of tank used in Experiments 1, which was slightly modified for Experiment 2 to use a recirculating water bath rather than flow-through to achieve desired temperatures. Experiment 3 was conducted with the same data acquisition and overall set-up but in larger seawater tables to accommodate 10 shrimp and sheltering habitat. Sample sizes, treatments, and groupings for each experiment appear in Table 1.