Excerpt from the Editor’s Page of the January/February 2021 issue of CORAL Magazine.

This issue should probably come with a warning label: CAUTION—Contents may trigger obsessive, addictive, and budget-stretching behaviors.

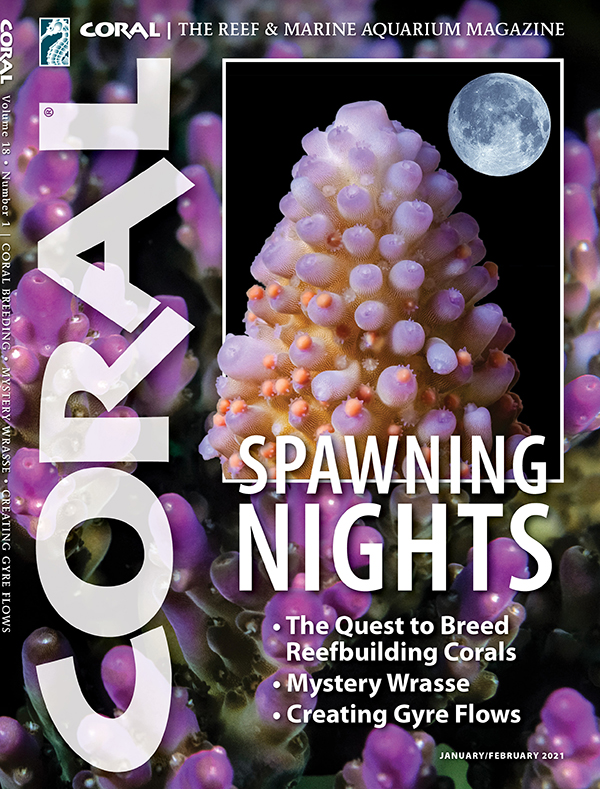

Who among us has not thrilled at the discovery of reproductive behaviors in our aquariums—perhaps tiny livebearer fry spotted in a childhood 10-gallon tank, or a clutch of clownfish eggs magically appearing one morning in a community reef system? Now, as this issue’s cover stories show, we are on the threshold of a new level of captive breeding: the sexual reproduction of stony corals in home reef aquariums.

Among marine biologists, a first encounter with spawning reef corals is often recalled as a life-changing experience. “Two decades ago, I witnessed coral spawning for the first time,” says Dr. Nicole (Nikki) Fogarty, who is credited with the first lab-induced spawning of the Caribbean species: Mountainous Star Coral, Orbicella faveolata, and Knobby Brain Coral, Pseudodiploria clivosa. Dr. Fogarty recounts her own history for us:

“I still remember that night off Key Largo vividly. After many nights of disappointment—being run off the reef by waterspouts, our boats breaking down, wrangling volunteer divers, and uncooperative corals—IT happened! It was a large Mountainous Star Coral that was likely well over 100 years old. Egg-sperm bundles were appearing in the coral’s polyps, and I freaked out!

Not without difficulty, we secured a gamete collection net over the coral and settled down to watch; we waited and waited. Just when I had given up hope, the giant colony exploded in synchronized pulsations, sending tiny pink spheres slowly floating up to the top of the net. As I looked around, surrounding colonies had also spawned, and it looked like a pink snowstorm. That night consisted of bone-chilling work with little sleep, getting the eggs fertilized and racing back in the dark to our lab to get the coral babies into their makeshift rearing facility.

“Fast forward 20 years, and my students and I sit in my air-conditioned lab at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, listening to Barry White and Marvin Gaye (to get the corals in the mood) and chatting. We have been monitoring captive corals for six days, but we are dry, comfortable, and rested. It is my turn to duck behind the blackout curtain, where red lights allow us to monitor the corals without disrupting spawning. Something catches my eye on one of the Mountainous Star Coral colonies—pink egg-sperm bundles, and once again, I freak out! IT is happening, the first time this species has spawned via artificial light and environmental manipulations in the laboratory. The next night our Knobby Brain Coral also spawns. Within hours, I am snuggled into my own bed, thinking: I could get used to this type of spawning research.”

This magazine lives at a unique intersection where marine scientists and reef enthusiasts cross paths, and Dr. Fogarty is quick to acknowledge the role of home aquarists in her lab’s success. “I was fortunate to have a graduate student, Kory Enneking, an expert hobbyist with years of experience in his home aquarium, set up my lab’s systems. It doesn’t take a Ph.D. to spawn corals in tanks. It takes a motivated, knowledgeable aquarist with a fundamental understanding of water chemistry, digital controllers, and how to keep and grow corals in a closed system.

“Spawning in captivity is a remarkable advancement. Not only can hobbyists witness this awe-inspiring phenomenon at home, they can rear baby corals, taking pressure off wild populations. It can also allow scientists to rear millions of larvae to outplant to degraded reefs and conduct experiments that enhance our knowledge of the factors that have led to coral decline—all the while removing logistical challenges, hazards, and the expense of collecting coral spawn in the wild.”

And so, here’s to 2021: May it be a gamechanging year—perhaps even the dawn of new era in reefkeeping.

—James Lawrence

Shelburne, Vermont