John E. Randall, Ph.D., John L. Earle, and Robert Whitton

Excerpt from CORAL Magazine, Volume 16.5, September/October 2019

The term “mobbing” in animal behavior refers to the collective aggressive response by a group of potential prey animals to a predator. Most examples have been demonstrated in birds, such as crows, jays, and gulls, but several publications, such as one by Wallace J. Dominey (1983), have described this behavior in fishes.

Lead author Dr. John E. “Jack” Randall, former Curator of Fishes of the Bishop Museum and member of the Graduate Faculty in Zoology of the University of Hawai’i.

In his research, Dominey released a large snapping turtle near the nesting areas of freshwater Bluegills, Lepomis macrochirus, and tracked their behaviors. Dominey said he observed “…as the turtle moved through a colony, dozens of nesting males, gravid females and males without nests rapidly approached (some individuals to within several centimetres) and followed the turtle across numerous territories until it left the colony area.”

Mobbing in fishes also takes place when several individuals overwhelm the defense of a benthic area containing a sought-after food resource that is guarded by a single or a few individuals. When the purpose of forming an aggregation is to gain access to a food source, the term “trophic mobbing” is used. In marine fishes, the food targeted in mob attacks may be algae, coral polyps, or the ova of a nesting species. Examples are provided here of trophic mobbing by fishes.

Turf Raids

Some herbivorous fishes are known to form feeding aggregations that overcome the defenses of other territorial algal-feeding fishes. Randall (1961) described the feeding aggregations of the Convict Surgeonfish, Acanthurus triostegus, noting that they were at times harassed by the territorial Whitecheek Surgeonfish, Acanthurus glaucopareius (now A. nigricans). Barlow (1974) reported on A. triostegus feeding individually where the pugnacious Brown Surgeonfish, A. nigrofuscus, was not common, but forming aggregations where it was.

Convict Surgeonfish (Acanthurus triostegus) invading the algae patch of the Brown Surgeonfish Hawaiian Sergeant (Acanthurus nigrofuscus), O’ahu. Image: John Randall

Ormond (1980) discussed this behavior for the Sailfin Tang, Zebrasoma veliferum (now Z. desjardinii) in the Red Sea. Randall (2002) has documented it for the Indo-Pacific surgeonfishes Acanthurus auranticavus, A. leucopareius, A. leucosternon, and A. triostegus, as well as the western Atlantic Blue Tang, A. coeruleus. A. coeruleus sometimes forms mixed schools with A. bahianus and A. chirurgus. George Barlow (pers. comm.) observed large feeding aggregations of the Forktail Rabbitfish, Siganus argenteus, in Guam overwhelm territorial herbivorous fishes, and we have observed this for the Sea Chub, Kyphosus sandwicensis, in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

We provide an accompanying photograph of several individuals of the herbivorous Convict Surgeonfish that have frightened a guarding damselfish away from its private pasture of benthic algae.

Nest Robbers

Another food source for trophic mobbing is a benthic patch of eggs that is guarded by a parent. Photo on page 106, bottom, is an example of a male damselfish guarding its egg mass, and the photo on page 110, top, is the result of the mobbing of butterflyfish.

Male Hawaiian Sergeant guarding egg patch. Nesting damselfishes are notoriously aggressive in defending their territories, even attacking divers who encroach on their territory. Image: John E. Randall

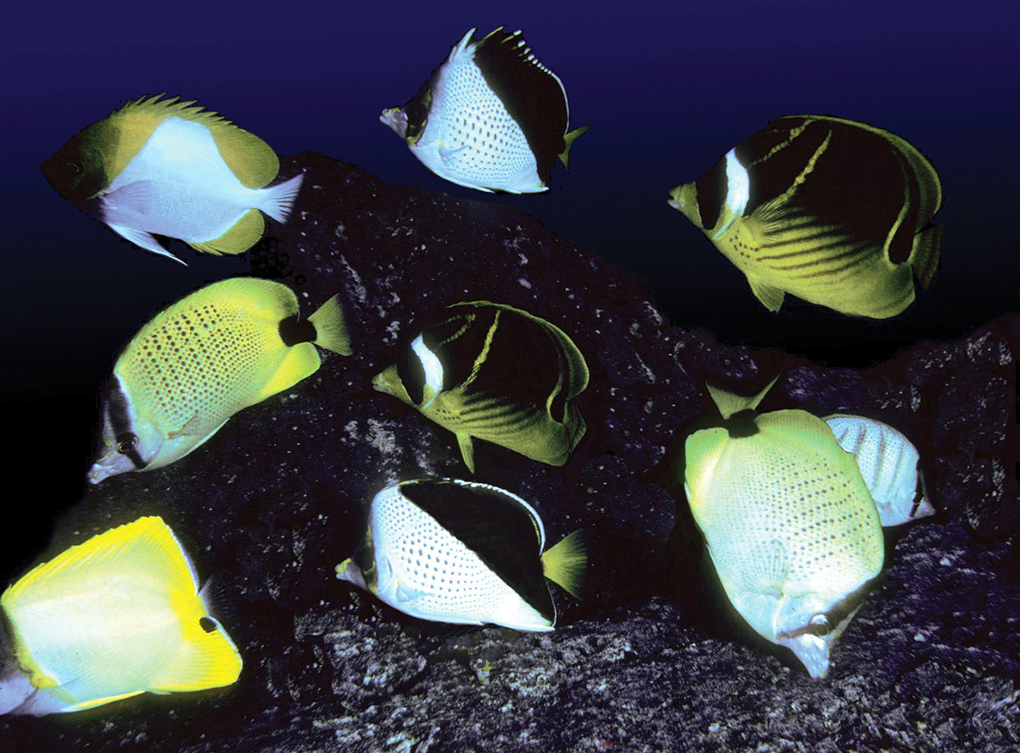

More than one species of egg predator may take advantage of such an opportunity. Earle has a photograph, also taken in the Hawaiian Islands, of the ova of the same species of damselfish being eaten by six different species of butterflyfishes shoaling together (published in Randall (2007: 275, middle, page 110).

Aggregation of the Milletseed Butterflyfish (Chaetodon miliaris) feeding on benthic ova of the Hawaiian Sergeant (Abudefduf abdominalis). Image: John L. Earle

Earle also videotaped the Sunburst Butterflyfish, Chaetodon kleinii, feeding en masse on the demersal ova of Abudefduf vaigiensis at the island of Komodo in Indonesia, as well as the ova of the Eastern Pacific Bumphead Damselfish, Microspathodon bairdii, being eaten by so many Cortez Rainbow Wrasse, Thalassoma lucasanum, that it abandoned its defense of the nest (Costa Rica, 2005).

Colorful Sunburst Butterflyfish (Chaetodon kleinii) gobble up Pacific Sergeant (Abudefduf vaigiensis) eggs in Komodo National Park, Indonesia. Image: © Frank Baensch.com

Swarming Corallivores

We report coral polyps as another protected food resource that becomes available to fishes by mobbing behavior. Small territories of coral of the genus Pocillopora are aggressively guarded by two species of damselfishes of the genus Plectroglyphidodon. We have observed mobbing by four species of butterflyfishes of the genus Chaetodon on reefs in the Hawaiian Islands, Tuamotu Archipelago, Line Islands, and the island of Komodo in Indonesia.

Earle observed and took video of the Reticulate Butterflyfish, Chaetodon reticulatus, at a depth of 10 m on the outer reef near Avatoru Pass of Rangiroa Atoll, Tuamotu Archipelago, in January 2004. A school of approximately 23 individuals may be observed in the video record foraging on colonies of Pocillopora meandrina in a loose aggregation. The school became a tight cluster when it encountered an area defended by the Johnston Island Damselfish, Plectroglyphidodon johnstonianus. As seen in the video, the photographer easily approached the normally wary C. reticulatus when the species was mobbing.

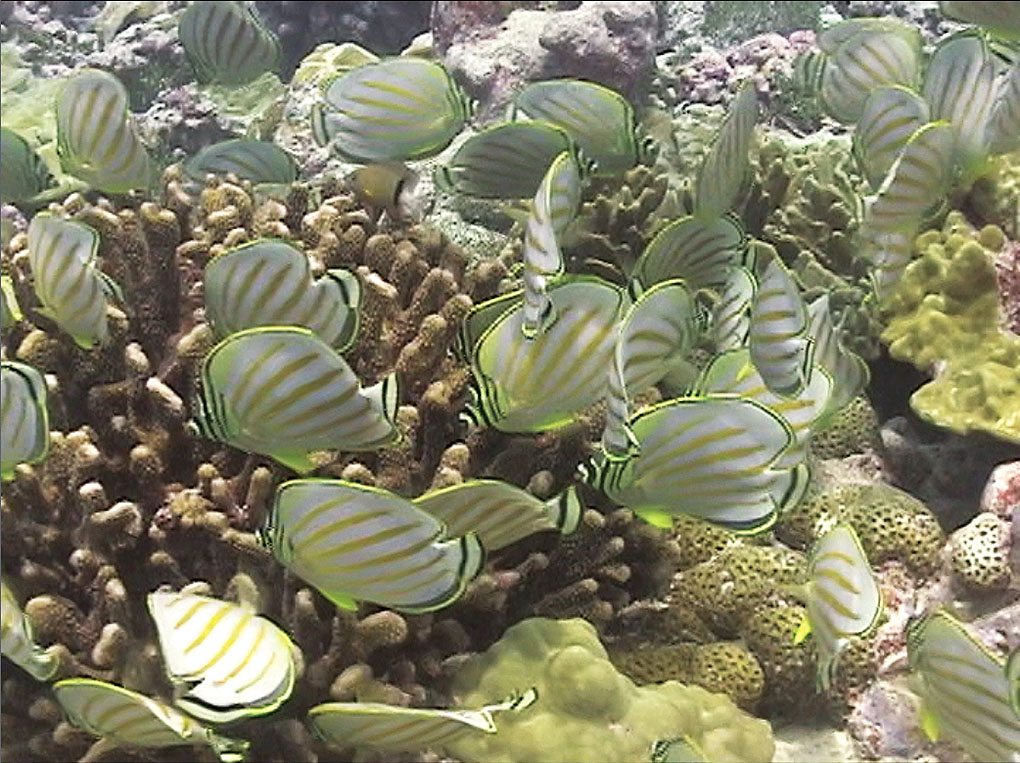

Trophic mobbing by Ornate Butterflyfish, Chaetodon ornatissimus, was videotaped by Earle in the late morning of 26 March 2005 at 15 meters depth on a reef with mixed Pocillopora and Porites coral cover off Poland village on Christmas Island (Kiritimati), Line Islands. In the video, a school of more than 80 individuals may be observed feeding primarily on Pocillopora meandrina. The school became a compact aggregation when it entered the defended territory. The coral head fed upon at the start of the video is defended by one individual of the Blackbar Devil Damselfish, Plectroglyphidodon dickii (page 110, bottom, extracted from the video). The overwhelmed damselfish resumed active defense only after most of the butterflyfish departed.

In a second video clip of the same mobbing aggregation provided by Whitton, a head of Pocillopora meandrina is defended by an individual of P. johnstonianus that also resumed vigorous defense only after most of the individuals of C. ornatissimus departed.

Six species of butterflyfishes feeding on the ova of a damselfish at Kona, Hawai‘i, after the guarding parent was driven away. Image: John L. Earle

Most individuals of Chaetodon reticulatus at Rangiroa and C. ornatissimus at Christmas Island were observed to exhibit normal pair behavior. Trophic mobbing is an apparently rare alternate feeding strategy that may arise when there is a high density of defended coral heads and a local population of butterflyfish large enough to provide the feeding schools.

Trophic mobbing may be predicted for similar coral-feeding species with large home ranges, such as the butterflyfishes Chaetodon collare, C. meyeri, and the those of the C. trifasciatus complex, but it would not be expected for coral-polyp-feeding species of butterflyfish, such as C. baronessa or C. trifascialis, which are small territory-resource defenders.

Ornate Butterflyfish (Chaetodon ornatissimus) form a mob to feed in a territory defended by an overwhelmed Blackbar Devil Damselfish (Plectroglyphidodon dickii), Christmas Island, Kiribati. Image: John L. Earle

Conclusions

In summary, trophic mobbing of a resource of benthic algae guarded by resident damselfish may be expected where there is a population of a herbivorous surgeonfish large enough to form a compact aggregation to overcome the defense of individual damselfish. Zooplankton-feeding butterflyfish may form a trophic mob to feed on the ova of nesting damselfishes. Similarly, an individual of a butterflyfish guarding live coral may be forced to abandoned its territory when an aggregation of another species of coral-feeding butterflyfish invades its territory.

References

Dominey, Wallace J. “Mobbing in Colonially Nesting Fishes, Especially the Bluegill, Lepomis Macrochirus.” Copeia, vol. 1983, no. 4, 1983, pp. 1086–1088. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1445113.

Randall, J. E. “Overgrazing of algae by herbivorous marine fishes.” Ecology 42(4): 812-812. https://doi.org/10.2307/1933510