Advanced Aquatics: The Butterfly Chronicles, Part 1, by Matt Pedersen, as published in the November/December 2018 issue of CORAL Magazine.

THE BUTTERFLY CHRONICLES, Part 1 (read Part 2)

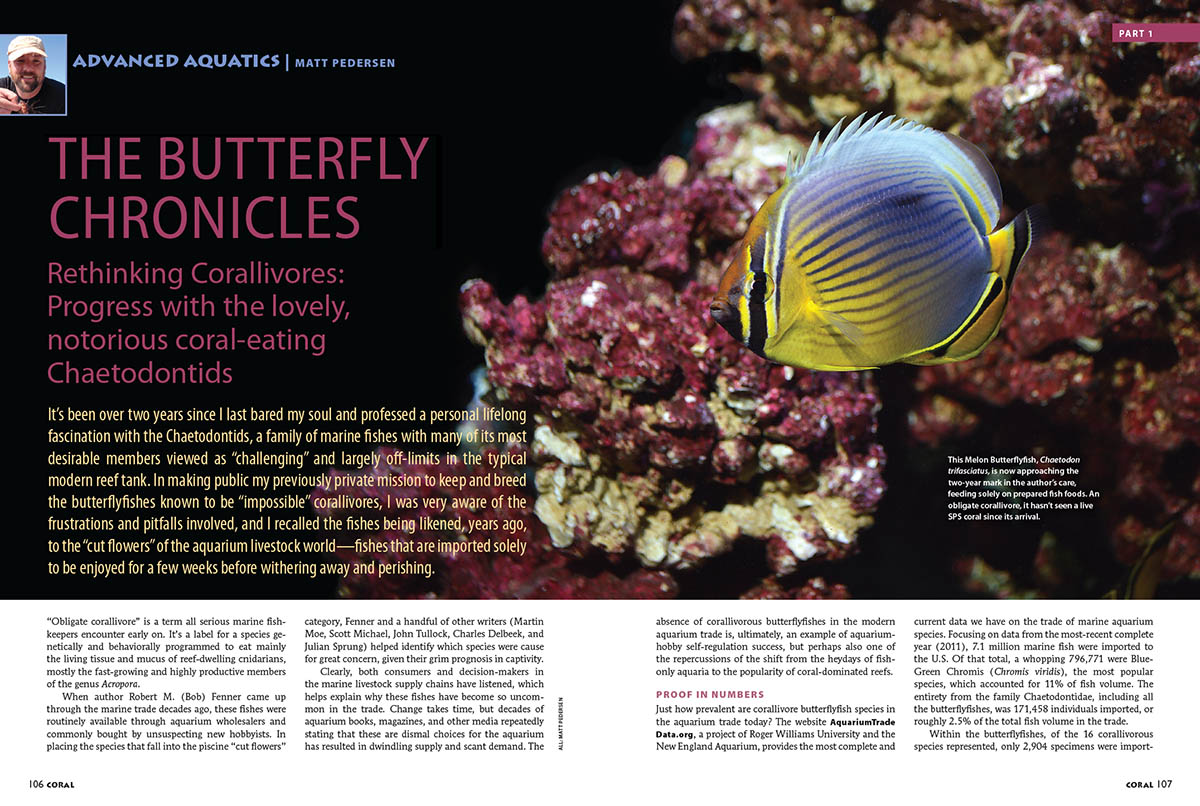

Rethinking Corallivores: Progress with the lovely, notorious coral-eating Chaetodontids

text and images by Matthew W. Pedersen

It’s been over two years since I last bared my soul and professed a personal lifelong fascination with the Chaetodontids, a family of marine fishes with many of its most desirable members viewed as “challenging” and largely off-limits in the typical modern reef tank. In making public my previously private mission to keep and breed the butterflyfishes known to be “impossible” corallivores, I was very aware of the frustrations and pitfalls involved, and I recalled the fishes being likened, years ago, to the “cut flowers” of the aquarium livestock world—fishes that are imported solely to be enjoyed for a few weeks before withering away and perishing.

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of CORAL: Click to order this back issue for your collection.

“Obligate corallivore” is a term all serious marine fishkeepers encounter early on. It’s a label for a species genetically and behaviorally programmed to eat mainly the living tissue and mucus of reef-dwelling cnidarians, mostly the fast-growing and highly productive members of the genus Acropora.

When author Robert M. (Bob) Fenner came up through the marine trade decades ago, these fishes were routinely available through aquarium wholesalers and commonly bought by unsuspecting new hobbyists. In placing the species that fall into the piscine “cut flowers” category, Fenner and a handful of other writers (Martin Moe, Scott Michael, John Tullock, Charles Delbeek, and Julian Sprung) helped identify which species were cause for great concern, given their grim prognosis in captivity.

Clearly, both consumers and decision-makers in the marine livestock supply chains have listened, which helps explain why these fishes have become so uncommon in the trade. Change takes time, but decades of aquarium books, magazines, and other media repeatedly stating that these are dismal choices for the aquarium has resulted in dwindling supply and scant demand. The absence of corallivorous butterflyfishes in the modern aquarium trade is, ultimately, an example of aquarium hobby self-regulation success, but perhaps also one of the repercussions of the shift from the heydays of fish-only aquaria to the popularity of coral-dominated reefs.

Proof In Numbers

Just how prevalent are corallivore butterflyfish species in the aquarium trade today? The website AquariumTradeData.org, a project of Roger Williams University and the New England Aquarium, provides the most complete and current data we have on the trade of marine aquarium species. Focusing on data from the most recent complete year (2011), 7.1 million marine fish were imported to the U.S. Of that total, a whopping 796,771 were Blue-Green Chromis (Chromis viridis), the most popular species, which accounted for 11% of fish volume. The entirety from the family Chaetodontidae, including all the butterflyfishes, was 171,458 individuals imported, or roughly 2.5% of the total fish volume in the trade.

Within the butterflyfishes, of the 16 corallivorous species represented, only 2,904 specimens were imported. These fish are common in the wild, none is overfished, and none is threatened, except where large areas of reef have been bleached. Collectors simply have been taught not to catch them, most exporters won’t buy or ship them, and they are mostly too small for food. As a result, most of these species were imported in quantities of less than 200 per year; compare that to the 82,339 Coral Beauty Angelfish (Centropyge bispinosa) that were imported in that same time period. Corallivorous butterflyfishes represented less than a 20th of one percent (0.05%) of the marine fish exports in that year, less than one fish in 2,500 or about 400 fish per million aquarium fish in the trade. On average, a typical independent local aquarium shop might sell two or three of these butterflies a year, and most dealers sell none unless a customer specifically requests them. Effectively, these fish are not present in the trade. Some are heartachingly beautiful, intelligent and appealing, but virtually no one is trying to keep them.

Arabian Butterflyfish, Chaetodon melapterus, eating food coated onto the skeleton of a coral. This individual remains alive today, well over 1.5 years in captivity, solely consuming aquarium fare.

Reasons For Hope

We have all heard of outliers: corallivores (both butterflyfishes and others, such as the Harlequin or Longnose Filefish, Oxymonacanthus longirostris) that take flake foods from their owners’ fingers. A handful of aquarists in Asia have documented success getting corallivores to accept foods other than coral. For the moment, I’ve dubbed this simply the “Asian Technique,” and I believe it has a few key factors. First and foremost, these aquarists are close to the source. The fish they are starting with are in good condition and have not endured long transits before arriving in their care. I believe this is a major factor in their success. The other aspect of their success includes a common technique of feeding “clams on the half shell,” or more often, a mix of prepared foods pressed into shells or coral skeletons. One of the mixes that is repeatedly utilized is something one aquarist called “hamburger mix,” which is nothing more than grated table shrimp and Tetra ColorBits or other nutrient-dense pellets mixed together.

Hurdles: The Ideal Way to Tackle Corallivores

I’ve had the ideal corallivore husbandry experiment designed in my head for years. I’d want to get short supply chain fish from drug-free collection regions. I’d want them all of a similar size, on the younger side but perhaps not tiny fishes. I’d want at least 6-8 specimens, and each one could be placed into its own aquarium or compartment in a dedicated system, with two first-food options being tested. By repeating this experiment two or three times, I would be able to identify the perfect way to handle a wild-caught corallivorous butterflyfish.

Pragmatically, this experiment has been impossible to conduct. Corallivorous butterflies are rarely available, and when they are, there are often only one or two at any given supplier. Their sizes vary wildly, but they usually fall into the category of “larger than you’d want”—older fish that are set in their ways, overly sensitive to shipping stress, and exceptionally difficult to adjust to captive life. The supply chain on these fishes is a gamble at best; it’s impossible to know whether a fish has been collected with cyanide and is thus doomed no matter what you do. The sporadic nature of their availability generally means you’re unable to truly plan ahead; you have to jump at the opportunity to work with a species when it happens.

Feeding: Ideas & Lessons Learned

After reviewing all my experiences and those of others, it seems appropriate to go back and question the notion that these fish are impossible to feed in captivity. In terms of dogma, we can at least put to rest the notion that these fish are completely unwilling to consume any aquarium diet, and that they cannot live on anything other than live coral. These “facts” are simply disproven.

I must preface my story with my personal ethic for keeping corallivores. When I purchase these fishes, I make the mental commitment that I will buy, and feed, as much live coral as it takes to keep these fish alive while in my care, should they refuse all my culinary offerings. Over the years, several suppliers have been very supportive of this, willing to sell me poorly-colored or damaged corals at a reduced price for the purpose of “fish food.” Frankly, I don’t know that you could buy enough coral to keep a corallivore alive in the average quarantine tank setting, and while on rare occasions live coral has been ideal for eliciting an initial feeding response, most of the time the fish can be coaxed to try something else.

I’ve had consistent success utilizing two possible first-food items. Mussels are readily available at any seafood counter; they can easily be split and served on the half shell. While I initially believed that they needed to be “live,” once I tried splitting them and freezing them for later use, I found that it didn’t seem to matter. However, some colleagues have cited mussels as a vector for pathogens, which is of course concerning.

Applying food to a coral skeleton is a method that makes sense, and I can trace it back as early as 1976. Robert P. L. Straughan notes in The Salt-Water Aquarium in the Home, 4th Edition, page 108, that “sometimes the butterflyfish will eat scallop which has been pressed into a piece of the rose coral to simulate the live polyp.” The fly fisherman in me understands this concept as an example of “matching the hatch”: just as we learn that there are times when a trout will only accept a fly pattern which is an identical match for the size, color, and behavior of its preferred insect, putting flake and pellet foods, or even Mysis and brine shrimp, in front of a devoted coral-eater is just as likely to fail as when you offer the wrong fly pattern to a trout. Presenting a food option that closely mimics the desired prey is often crucial to the success in getting a fish to bite, whether the objective is to fool it into taking a hook or to coax it to find a way to survive on a foreign diet in captivity.

Over the years, I’ve used this method as part of my arsenal to train Harlequin Filefish, and I found it equally useful with corallivorous butterflyfishes. What I’ve found most effective are gel-based diets that are prepared on-site, specifically Repashy Superfood’s Spawn & Grow formulation. This high-calorie food is prepared with boiling water, and is a viscous liquid for a brief period, long enough to coat a coral skeleton in a thin layer of rich paste. Once the gel sets up, the food stays put and can be left in an aquarium for up to 24 hours. Batches of the food can be made and stored in the refrigerator or the freezer for longer periods. Furthermore, the food itself can be augmented in any way you desire by simply mixing in other ingredients as the gel cools.

Repashy Spawn & Grow is a go-to base for a first food, mixed and spread on old coral skeleton or rock.

In this manner, I’ve broadened the dietary diversity by adding in various pellet foods, including Sustainable Aquatics Hatchery Diet, Spectrum’s Thera A Pellets, Tetra ColorBits, PE Mysis Pellets, and, perhaps most promisingly, the Panta Rhei Nouri Polyp formulation. In time, eating these palatable, nutritious foods within the gel could help train a fish onto these foods on its own.

A newly-received Indian Redfin or Melon Butterflyfish, Chaetodon trifasciatus, sampling food from a coral skeleton in a quarantine aquarium.

Nouri Polyp is a product that deserves a little more discussion. Just as we now have multiple frozen fish diets which incorporate sponge-based materials for spongefeeding angelfish, we now have a pellet food that has been formulated with the corallivore in mind. Of course, stripping the flesh off fields of Acropora in order to make a fish food out of them seems impossible and absurd, so the flesh of another cnidarian group, the medusazoans (specifically jellyfish) is used, and is listed as 10% of the invertebrate ingredient list. The idea is novel, and I suspect it aims to address the hypothesis that there is some nutritional component in coral flesh that a corallivore can’t live without; maybe jellyfish contain that component. I don’t know whether there is any science or benefit to using this food, but I choose to include it in my offerings both as a hedge (in case I’m wrong about the critical nutrient argument) and to support a company that’s willing to go out on a limb to create a product for a group of fishes that most believe no one should even keep.

Given all my personal experiences, I am inclined to conclude at this time that, while it is challenging, getting these fishes to eat can be accomplished. When I’ve had long-term success, it has been difficult to wean the fish off the initially accepted food; instead, I’ve found myself trying to augment. Furthermore, I’ve had repeated experiences where even minor, temporary reductions in feedings can put these fish on a rapid decline that is difficult to turn around. They are grazers, picking at food constantly throughout the day, and their dependence on food is understandable. However, it also serves as a reminder that while I can get them to eat something routinely, it may or may not be the best food for them. We simply don’t know enough, and the experiments should continue.

In the next issue, we will look at what I now see as the Number One Problem in Corallivore Husbandry and the hands-on techniques that I believe may help advance our efforts at feeding, keeping, and eventually breeding these captivating butterflies.

Readers are invited to add their comments and their own experiences below.

if your getting corals to use, one option to try could be crushing the coral in a mortar and pestle and then adding it to a mix to include the “flavor” of a coral which could trigger a feeding response. I think that the odor/scent of the food item can be a missed opportunity in acclimating some animals.

Edward, this is a very interesting idea.