Raised from wild eggs, these post-larval Convict Tang, Acanthurus triostegus, are undergoing their final transition into juvenile coloration in Frank Baensch’s Hawaii Laboratory. Says Baensch, “larvae undergoing transformation. All have bars, are acting like juveniles and about half have green/brown pigment. So, finally, some color!” Image Credit: Frank Baensch

Frank Baensch has always been an aquarist on the bleeding edge—in the realm of many unknowns and no shortage of risks. You may know Baensch as the first to breed Centropyge angelfish at the Reef Culture Technologies (RTC) laboratory in Hawaii some 17 years ago. More recently, Baensch’s focus has shifted from a captive-bred research model to utilizing the RTC labs under the banner of the Hawaii Larval Fish Project (HLFP).

Revisiting the Hawaii Larval Fish Project

Pioneering marine fish breeder Frank Baensch of Reef Culture Technologies and the Hawaii Larval Fish Project.

Baesnch shared this project in great detail in the March/April 2014 issue of CORAL Magazine, but as a brief recap, Baensch skips the broodstock phase of a captive-breeding project, instead sourcing fertilized fish eggs from the ocean waters around Hawaii, the logic being that Mother Nature is going to produce the highest quality, best possible eggs.

Conversely, captive-held broodstock may fail to produce eggs of a similar quality, ultimately hampering a rearing effort before it even gets started. By utilizing wild-sourced eggs, Baensch (and the HLFP) minimize their impact on the reef (no broodstock collection), circumventing one pitfall of captive-breeding research to focus squarely on larviculture; rearing those high-quality wild eggs to juvenile fishes. Because of this lingering tie to the ocean, Baensch’s current work under the Hawaii Larval Fish Project fails to meet the strict definition of “captive-bred,” but the results are groundbreaking in the field of aquaculture research.

This methodology has repeatedly shown Baensch to be leading the pack when it comes to growing marine fish in captivity. Before the world’s first captive-bred Anthias, nevermind the amazing commercial availability of the deepwater Borbonius Anthias via Biota Marine Life Palau, it was the Hawaii Larval Fish Project that cracked the code with multiple Anthine species, most notably the very rare Hawaiian Yellow Anthias (Odontanthias fuscippinis) in 2013. Before we had the world’s first captive-bred Butterflyfish (at the hands of Baensch), it was the HLFP that brought us an aquacultured Schooling Bannerfish (Heniochus diphreutes) reared from field-collected eggs.

The World’s First Aquacultured Tang from the Genus Acanthurus

On April 30th, 2018, Frank Baensch privately shared some news with his friends on social media: “After an extended break from fish culture, it felt good to be back in the hatchery again. Here’s a clip of Convict Tang (Acanthurus triostegus) post-larvae becoming juveniles after 90+ days in culture. The fish were raised from wild collected eggs for the Hawaii Larval Fish Project.”

In the subsequent discussion, Baensch noted that the fish had been reared entirely on cultured feeds. “The larvae have similar rearing requirements to Yellow Tang and Blue Tang,” wrote Baensch.”I am excited (and wanted to prove to myself) that surgeonfish larvae can be raised at my facility – in a small culture tank with limited saltwater supply. Also, no [wild] plankton was used, which could make this exciting for smaller inland breeders.”

Indeed, Baensch’s methodology–using limited water and cultivated feeds–means that a land-locked fish breeder, thousands of miles from the ocean may be able to produce the live feeds necessary to rear a captive-born Convict Tang, ultimately replicating a success like this. However, it’s going to be a lot of work, as Baensch went on to relate. “While the larvae are quite robust, they do require almost constant feedings, which makes culturing them very time-consuming. The little guys pretty much took up the last 3+ months of my life.”

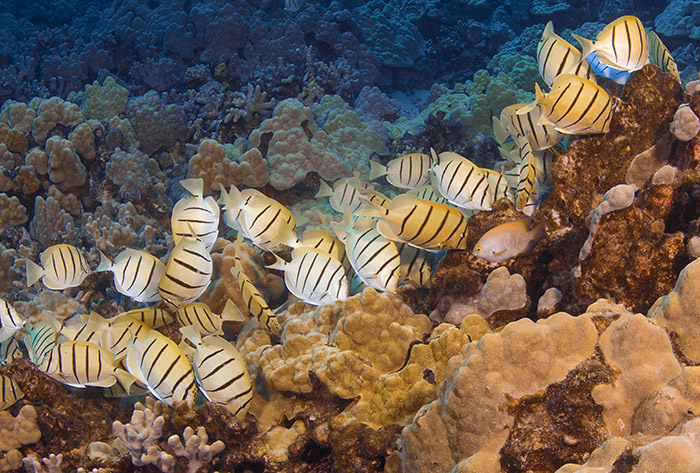

Shoal of wild Manini (Convict Tangs) on a Hawaiian reef. Ocean Image Photography/Shutterstock.

An Optimistic Future View

Baensch’s track record suggests that his latest accomplishment may foreshadow another captive-breeding breakthrough on the horizon (in this case, a species within the genus Acanthurus). We only have two Tang species on the captive-bred list so far: first the Yellow Tang (Zebrasoma flavescens) at the Oceanic Institute at Hawaii Pacific University, followed rapidly by the Pacific Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) at University of Florida’s Tropical Aquaculture Lab.

With wild-harvested species like the popular Powder Blue Tang (Acanthurus leucosternon), or perhaps the sought-after Achilles Tang (Acanthurus achilles), we can only hope that this work leads to the successful cultivation of these high-demand and sometimes difficult-to-keep species. We look forward to whatever goal Frank Baensch sets his sights on next!

Further Reading

You can review Frank Baensch’s entire aquaculture research career on his newest website, FrankBaensch.com. Both captive-breeding and larval-rearing accomplishments are prominently cataloged in Baensch’s fish culture research blog at https://www.frankbaensch.com/marine-aquarium-fish-culture/my-research/

We look forward to sharing more from Baensch in an upcoming issue of CORAL Magazine.