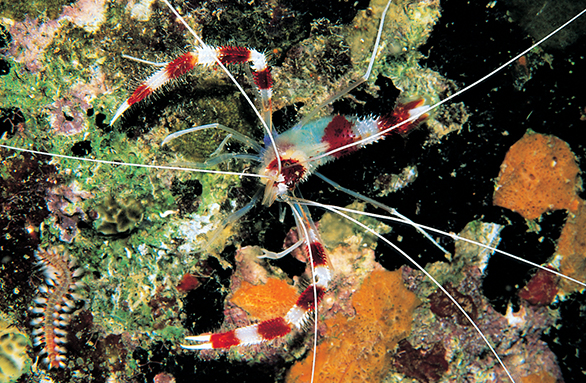

The Coral Banded or Boxing Shrimp, Stenopus hispidus. Image: Scott Michael, 101 Best Marine Invertebrates, Microcosm.

Whether you call it the Banded Coral Shrimp, the Coral Banded Shrimp, or sidestep the debate by calling it a Boxing Shrimp, Stenopus hispidus is one of the more commonplace and showy ornamental shrimp species kept in marine aquariums. When we stop to think about where our animals come from, or wonder why some are common and others in the same family are rare, we often find that there has been little or no research done on species that are not considered economically significant. Now, a team of researchers based in Hawaii and Florida has taken a serious first look at how Stenopus hispidus might have spread from sea to sea around the globe.

The shrimp’s long larval duration of 4 to 8 months (this is one of the main obstacles in the captive production of species like this) is no doubt a critical factor that helped this species achieve a circumtropical distribution; it spends months adrift in the planktonic soup before settling on an ideal habitat. However, researchers had never really investigated the extent to which populations located in different oceans are genetically connected. These populations have outwardly appeared to overcome the biogeographic barriers that at times are cited as an obstacle responsible for the differentiation of one species into two or more related species. But have they succeeded?

In the new open-access article in the journal PeerJ, “The little shrimp that could: phylogeography of the circumtropical Stenopus hispidus (Crustacea: Decapoda), reveals divergent Atlantic and Pacific lineages,” the researchers seek to address challenging questions. Are these populations genetically connected, and, if so, how? Where did the species originate? How did it spread across the planet? Is it even appropriate to consider all populations of this colorful shrimp the same species?

In doing genetic testing of Banded Coral Shrimp from collection sites spread over 27,000 km (about 17,000 miles), the researchers found that the Western Tropical Atlantic population is older than its Indo-Pacific relatives and that the two lineages diverged sometime in the distant past, estimated at 710,000 to 1.8 million years ago. The scientists say the findings pose new questions about the events that led to the divergence of the two populations, with further study needed to understand how the diminutive species dispersed over such great distances.

Dr. Rob Toonen, invertebrate zoologist and co-author of the new study.

The lead author of the paper is Ale’alani Dudoit, a graduate student in the Toonen Lab at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, working under Dr. Rob Toonen, a well-known invertebrate zoologist (and member of the CORAL Magazine Board of Advisors).

Abstract

The banded coral shrimp, Stenopus hispidus (Crustacea: Decapoda: Stenopodidea) is a popular marine ornamental species with a circumtropical distribution. The planktonic larval stage lasts ∼120–253 days, indicating considerable dispersal potential, but few studies have investigated genetic connectivity on a global scale in marine invertebrates. To resolve patterns of divergence and phylogeography of S. hispidus, we surveyed 525 bp of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) from 198 individuals sampled at 10 locations across ∼27,000 km of the species range. Phylogenetic analyses reveal that S. hispidus has a Western Atlantic lineage and a widely distributed Indo-Pacific lineage, separated by sequence divergence of 2.1%. Genetic diversity is much higher in the Western Atlantic (h = 0.929; π = 0.004) relative to the Indo-Pacific (h = 0.105; π < 0.001), and coalescent analyses indicate that the Indo-Pacific population expanded more recently (95% HPD (highest posterior density) = 60,000–400,000 yr) than the Western Atlantic population (95% HPD = 300,000–760,000 yr). Divergence of the Western Atlantic and Pacific lineages is estimated at 710,000–1.8 million years ago, which does not readily align with commonly implicated colonization events between the ocean basins. The estimated age of populations contradicts the prevailing dispersal route for tropical marine biodiversity (Indo-Pacific to Atlantic) with the oldest and most diverse population in the Atlantic, and a recent population expansion with a single common haplotype shared throughout the vast Indian and Pacific oceans. In contrast to the circumtropical fishes, this diminutive reef shrimp challenges our understanding of conventional dispersal capabilities of marine species.

Citation:

(2018) The little shrimp that could: phylogeography of the circumtropical Stenopus hispidus (Crustacea: Decapoda), reveals divergent Atlantic and Pacific lineages. PeerJ 6:e4409 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4409

Read it now:

The full article is available, free of charge, as an open-access publication. You can read it here.

The 101 Best MARINE INVERTEBRATES

By Scott W. Michael

How to Choose & Keep Hardy, Brilliant, Fascinating Species That Will Thrive in Your Home Aquarium (Adventurous Aquarist Guide) Paperback. Microcosm/TFH.

Available now from aquarium retailers or AMAZON books.