Article in CORAL Volume 15, Number 2. Large image by Frank Baensch. Left: Roger Steene.

Conspicuous Alternatives

Chaetodontoplus species for the rest of us

By Scott W. Michael

Excerpt from CORAL Volume 15, Number 2

March/April 2018

I’ll never forget the day I got my first shot at purchasing a Chaetodontoplus conspicillatus from a United States wholesaler. I first encountered these captivating beauties in a fish store in Brisbane, Australia, way back in the mid-1980s, and the “Conspic” immediately earned a place on my “I must get one of these” list. While the Aussie specimens had been moderately priced at the time, the U.S. supplier was asking $1,200 wholesale for this adult beauty. I weighed my options. It came down to one overarching consideration: Did I want to remain married to my wonderful, but more fiscally responsible, spouse or own a C. conspicillatus? I opted to stay wed; therefore, no Conspicuous Angel for Scott.

Now, here we are, decades later. This gorgeous fish still commands high prices, and I still cannot afford one. In fact, they are more expensive than ever: I recently saw 4-inch wild-caught individuals selling for nearly $3,500 online, and the captive-bred fish are over $5,000 apiece. The captive-raised fish seem to do very well in captivity, but the wild-caught individuals (especially large specimens that are accustomed to a diet of live sponges and tunicates) do not have the greatest track record when it comes to long-term survival.

Chaetodontoplus conspicillatus may be in a class of its own, but there are many other members of the 15-species genus Chaetodontoplus that make very attractive and hardy additions to the home aquarium. Let’s look at some of these “poor man’s” Chaetodontoplus species in detail.

Chaetodontoplus lifestyles

The members of the genus Chaetodontoplus are medium-sized angelfishes, the largest of which attains a total length of about 14 inches (35.6 cm); most species are less than 9.5 inches (24 cm) long. All the species of this genus occur in the East Indian and Western Pacific Oceans, with members ranging from southern Japan to western and southeastern Australia. Many members of the genus have rather narrow geographical ranges. For example, the Personifer Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus personifer) is only known from Western Australia, while the Ballina Angelfish (C. ballinae) is found along the coast of New South Wales and Lord Howe Island.

All the members of this genus are protogynous hermaphrodites; that is, they change sex from female to male. What is known about the social organization and mating systems of these fishes comes from a field study carried out on the Singapore Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus mesoleucus) in the Philippines (Moyer 1990) and observations of captive specimens of the Bluelined Angelfish (C. septentrionalis) and the Scribbled Angelfish (C. duboulayi) (Arai 1994). The field study on C. mesoleucus demonstrated that males defend a territory covering an area of 640 to 8,073 square feet (60–750 m²) where one or two females also roam. Males protect their mates from roving “bachelor” males and chase away potential egg predators, like wrasses and damselfishes. Aggression between females is rare, but males rush at and circle females when their paths cross.

However, during midday, males and females often forage together. Courtship begins about one hour before sunset, when the male performs a “soaring” display—he swims above the female, stops, and hovers with his fins extended and his body tilting 45 to 90 degrees to the bottom. The female ignores the male until she is ready to spawn, at which time she swims directly to the “rendezvous site” and initiates spawning with a mutual soaring display. The pair then rises in the water column, the male nuzzling the female’s abdomen with his snout. At the apex of the ascent—about 6 feet (1.8 m) off the bottom—the pair release their reproductive products and then, rather than smoking a cigarette, the male chases the female back to the reef (this is known as the after chase). In captive Scribbled Angels, the spawning act is similar, but males perform a motor pattern referred to as rapid swimming—the male rapidly swims around the female with his body inclined to one side and does not engage in soaring behavior.

The eggs of the Chaetodontoplus species that have been studied are spherical and pelagic, and in the Scribbled Angelfish they hatch about 24 hours after they are fertilized. In this species, the larvae are 2.4 to 2.6 mm total length at hatching.

Some members of the genus display subtle color differences between the sexes. For example, Scribbled Angelfish males are a more brilliant blue and have many fine, pale lines running down the sides of the body. Rather than having lines, females are peppered with numerous overlapping spots. During courtship and spawning, the male’s head becomes pale. The Scribbled Angelfish is also sexually dimorphic. The upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin in male specimens are pointed, while in females they are rounded, and males are typically larger than females. This size dimorphism is observed in most other Chaetodontoplus species as well.

In most of the Chaetodontoplus species the coloration of juveniles and adults differs greatly. For example, juvenile Bluelined and Black Velvet Angelfishes (Chaetodontoplus melanosoma) are black or dark brown overall and have a yellow stripe on the front of the head, behind the eye, on the dorsal and anal fin margins, and on the tail. (It turns out that black or brown with yellow markings is a common color scheme in a number of members of this genus.)

Hardiness and husbandry

When it comes to the adaptability or hardiness continuum, most Chaetodontoplus species fall somewhere in the middle. The biggest problem with these fishes is initiating a feeding response. It is not uncommon for a newly acquired Chaetodontoplus angel to go without eating for days or even weeks. The key to getting them to feed is to ensure that they experience as little stress as possible during the settling-in period. This means offering lots of suitable hiding places (I am talking about caves and “boltholes” large enough for the angelfish to completely hide in, which often requires some intentional aquascaping) and tankmates that are not likely to be overly hostile. To facilitate adjustment, make sure they have enough swimming room and keep them in tanks that are not in high-traffic areas. If you put them in an area where there is a lot of human activity, they are likely to spend more time hiding and less time looking for food. Keep your hands out of the tank as much as possible during the acclimation period and keep the room light dim, if possible. Dither fishes can also help bring a timid Chaetodontoplus, and any other shy fish for that matter, out of the shadows. Dither fishes are audacious types that spend their time out in the open, which conveys a sense of well-being to their more reclusive neighbors. Good dither fishes might consist of a shoal of hardy anthias or Chromis Damsels, a group of flagtails (Kuhlii spp.), or even a trio of Klein’s Butterflyfish (Chaetodon kleinii). Of course, the dither fishes should be fully acclimated to the tank before the angelfishes are added to achieve the desired result.

Another word of caution: feeding cessation often occurs when you move an acclimated individual from one tank to another, even if it was eating well prior to the relocation. Another unfortunate Chaetodontoplus truism is that young fishes (juvenile to subadult) almost always acclimate more readily than large adult individuals. I know young fishes are often not as chromatically striking as their elders, but it is best to start with individuals that are no more than 3 or 4 inches (7–10 cm) long if you want to assure acclimation. With all that said, the captive-bred fishes that are now available to aquarists adapt much better to aquarium life and fare than their wild counterparts. These fishes are often weaned on pelletized foods (see “Poma Rising,” p. 30, CORAL Magazine March/April 2018).

Chaetodontoplus species consume sessile invertebrates, with sponges comprising the bulk of their diets. Like all angelfishes, in captivity they should be fed a varied diet that includes some vegetable matter. There are so many good foods available these days, including formulas containing marine sponge. Clams on the half-shell (or finely chopped) and frozen mysid shrimp are good staples, as are the many frozen preparations that contain a mix of seafood. Some cubed foods are formulated especially for angelfishes. Make sure you supplement foods with Selco and other vitamin supplements (soak the food with the liquid supplement before feeding). Frozen preparations for herbivores, freeze-dried algae sheets, and any foods laced with Spirulina are great dietary supplements. Some individuals, especially those bred in captivity, will also accept dried foods (e.g., flakes or pellets).

Like many other pomacanthids, these fishes feed on encrusting invertebrates throughout the daylight hours; therefore, they are best fed three (or even more) small portions each day. While today’s aquarists certainly don’t encourage it in their display aquariums, I have always had good success getting these fishes to start feeding in an aquarium with lots of filamentous and macroalgae. This plant material can provide them with supplemental food until they are coaxed into accepting normal aquarium fare.

Unfortunately, like many of the species in the angelfish family, these fishes are very susceptible to parasitic attacks, including Crypt (Cryptocaryon irritans), Velvet or Coral Fish Disease (Amyloodinium ocellatum), Uronema marinum (another parasite, and an evil beastie!), and the viral infection Lymphocystis. Crypt and Velvet can be treated with copper and freshwater dips. Dropping the salinity precipitously in a tank that does not house invertebrates can also be useful in controlling Crypt outbreaks. If you choose to move one of these fishes from a display tank to a hospital tank, it is likely to stop eating (as discussed above), so be prepared for this. Color loss (due to a non-varied diet) and head and Lateral Line Disease are also potential Chaetodontoplus maladies.

Chaetodontoplus compatibility

Although I have kept juvenile members of this genus in reef aquariums without incident, as they grow they typically can’t refrain from nipping at large-polyped stony corals, tube worms, and Tridacnid clam mantles—but there are always exceptions. However, they often can be trusted with certain soft corals (e.g., Cladiella, Lemnalia, Lobophytum, Sinularia, and Sarcophyton) and tend to ignore mushroom anemones (corallimorpharians). That said, I have had some individuals that nipped at the oral discs of small and large sea anemones, feeding on the fecal material that these animals expelled, and in some cases they may start picking at the anemone’s tissue. Always remember that any potential coral-nipper is less likely to start bothering your precious cnidarians if it is well fed.

The members of this genus vary in their aggressiveness, but most species are less aggressive than many members of the genus Pomacanthus and much less so than the Holacanthus species. However, some species (e.g., Chaetodontoplus meredithi) can be quite pugnacious once they have become established in the aquarium. If you plan to keep a Chaetodontoplus with more passive species, the angelfish should be the last fish introduced. All of these angels tend to get more aggressive as they increase in size. You should avoid keeping members of the same species in an aquarium together, unless you simultaneously add a male and a female to a large tank (681–757 gallons/180–200 L or more). While sexing most species can be difficult, as mentioned above, some exhibit gender-related color differences. Even if you keep a pair together, you need to keep an eye on them—if one starts incessantly harassing its mate, you may have to separate them. More than one Chaetodontoplus species can be successfully housed in the same aquarium, especially in a large tank. It is often a good idea to add both fishes simultaneously or add the larger individual last. Although juveniles of different species can be housed together, if the two species are similar in appearance (which a number of juvenile Chaetodontoplus are) they are more likely to fight. I have seen occasions when more than one juvenile of similar (and even the same) species were housed together in a large tank with lots of hiding places, and were added to the tank simultaneously.

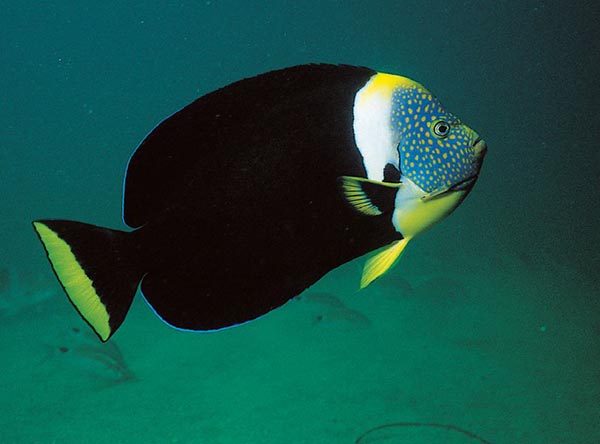

Conspicuous alternatives

There are a number of very appealing species in the genus that are affordable (or at least that cost much less than C. conspicillatus) and can make good aquarium residents once they get acclimated to their new homes. One of my favorites is the Bluespotted Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus caeruleopunctatus). This is a small angelfish (it maxes out at around 5.5 inches [14 cm]) that can happily thrive as an adult in a 100-gallon (378-L) tank. Its black to bluish-gray background coloration is bejeweled with bright blue speckles, and it has white-margined median fins and a bright yellow caudal fin. Even though it might chase intruders out of a favorite hidey-hole, I have found this species to be one of the least aggressive in the genus. Captive-reared individuals are always the best choice to ensure you get a well-treated individual to begin with.

The Black Velvet Angelfish (C. melanosoma) is another reasonable species that does well in the right aquarium environment. It is similar to a couple of other angelfishes: the Phantom Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus dimidiatus), which is known from eastern Indonesia, including the Raja Ampat Islands, the Maluku Islands, and northern Sulawesi and is a beautiful fish, and the Vanderloos Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus vanderloosi) from Milne Bay Province in Papua New Guinea. Chaetodontoplus melanosoma ranges from central Indonesia (western Java, Bali, and Komodo and Flores Islands) to the Philippines and is relatively common in the aquarium trade. Chaetodontoplus dimidiatus is less often encountered, and C. vanderloosi is a rarity (I have not heard of any entering the U.S. trade). The key to keeping these species is to obtain healthy fishes from the beginning—not surprisingly, individuals that have been mishandled or captured with chemicals are compromised and less likely to survive. I have found that a finicky C. melanosoma will rarely resist frozen mysid shrimp if everything else is right in its aquarium home. All three species top out at around 7 to 8 inches (18–20 cm). This means a tank of 150 gallons (568 L) should be suitable for an adult.

The Queensland Yellowtail Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus meridithi) was once the most misidentified fish in the pet fish trade. It was almost always sold at aquarium stores, and by many web fishmongers, as the “Personifer Angelfish,” but way back in 1990, fish expert Rudie Kuiter differentiated and described C. meridithi as distinct from its western relative, C. personifer, the true Personifer Angelfish. The two species are very similar. C. meridithi attains a maximum length of 9.8 inches (25 cm) and ranges from northern Queensland south to the central coast of New South Wales, Australia, and Lord Howe Island. It is a durable aquarium fish, and an acclimatized individual can be pugnacious, especially toward newly introduced relatives. It can be kept in a tank as small as 135 gallons (511 L), but the more room it has, the better. It is sexually dichromatic, with males sporting yellow spots on their faces.

Its close relative, the True Personifer Angelfish (C. personifer), is limited in distribution to West Australia and rarely makes it into the aquarium trade; when it does appear, it commands a high price. Individuals of 4.5 inches (11 cm) or less are usually identical in both species, but adults are reported to be distinguishable by caudal fin coloration (although this characteristic may be a bit variable). In adult C. personifer, the tail is typically all black with a wide yellow distal margin, while that of a large C. meridithi is usually yellow overall or dusky with a yellow edge. Like its “false” relative, the male Personifer Angelfish has yellow polka dots on a blue face, and the female’s face is a plain grayish-blue. This species gets larger than its eastern kin, attaining a maximum length of around 14 inches (35.5 cm); therefore, you will want a larger aquarium to keep a full-grown C. personifer (200 gallons/ 757 L should suffice).

The Scribbled Angelfish, Chaetodontoplus duboulayi, here displaying horizontal striping, a male characteristic.

Another Australian beauty is the Scribbled Angelfish (C. duboulayi). This beautiful, relatively common species occurs from northern Queensland to northwestern Australia (where it is often seen in the same habitats as C. personifer) and Papua New Guinea. It acclimates readily if it has lots of room, plenty of good hiding places, and no overly aggressive tankmates. That said, as it grows it may start throwing its weight around and pestering other pomacanthid and similarly shaped tankmates (e.g., butterflyfishes). This species gets about 10 inches (24 cm) long and does best in a tank of 180 gallons (681 L) or more. Fresh clams or mussels on the half-shell (rubber-banded to a piece of rubble) can often prompt a stubborn Scribbled to start feeding.

Chaetodontoplus septentrionalis, the Blueline Angelfish, was among the very first commercially-available captive-bred marine angelfish species.

The Blueline Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus septentrionalis) (not to be confused with the Blue Ring Angelfish, Pomacanthus annularis) is a magnificent fish that has become more common in the aquarium trade, thanks in part to aquaculture ventures. This attractive fish ranges from Taiwan and China to southern Japan, where it is common. An adult Bluelined Angelfish, which can reach about 10 inches (24 cm), can be kept in a 150-gallon (568-L) or larger aquarium. While these fish are not overly aggressive, be aware that they can be pugnacious once they have settled in. The Orangeface Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus chrysocephalus) is similar to C. septentrionalis and is known from the Java Sea, Indonesia to Cebu, Philippines. It differs from the Bluelined in that the male has a yellowish-orange head, a brown body anteriorly (shading to a darker brown/black posteriorly) with blue body stripes and a yellow tail. Females differ in that they have blue or whitish spots rather than stripes. The Maze Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus cephalareticulatus) is closely related and very similar in appearance.

Chaetodontoplus mesoleucus, the Singapore Angelfish, one of the most frequently encountered species of the genus.

The Singapore or Vermiculated Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus mesoleucus) is one of two black sheep in the family. It tends to be very inexpensive and is also one of the most wide-ranging species, having been reported from the Ryuku Islands, south to the Kimberly coast of western Australia, including the Philippines, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea. Both species show up in the aquarium trade, although the yellow-tail form is more common. The other black sheep is very similar, differing only in the color of its caudal fin: The Graytail Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus poliourus) has a grayish-white tail rather than a yellow tail. The Graytail is known from Palau, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. While they may simply look like color variants, genetic study has demonstrated that they are distinct species. Both show up in the aquarium trade, although the Singapore is more common. In captivity, both species can prove somewhat enigmatic—some individuals adapt quickly to aquarium life, while others hide constantly and never feed.

A sibling species to the Singapore Angelfish, this Graytail Angel, Chaetodontoplus poliourus, is exceedingly rare in the U.S. aquarium trade; potentially as few as a single specimen have been available.

The Ballina Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus ballinae) is a dramatically pigmented rarity that is native to Lord Howe Island and New South Wales. It is currently listed by Australia as a protected species and is not likely to be encountered in the aquarium trade.

Chaetodontoplus ballinae is a protected species, which suggests it may never be seen in the aquarium trade.

Finally, if budget and life circumstances ever allow you to consider a Conspicuous Angelfish (Chaetodontoplus conspicillatus), some planning and preparation is required. As is true of all members of the genus, you will increase your chances of success by keeping it in a large, well-established reef-type aquarium with lots of hiding places and nonaggressive tankmates in a quiet area of your home.

Long considered one of the “Holy Grail” species in the aquarium trade, the Conspicuous Angelfish, Chaetodontoplus conspicillatus, demands financial wherewithal and years of aquarium experience.

Choose your Conspic with care; they are now being bred in captivity, and these individuals readily acclimate to aquarium living, while wild-caught specimens often fail to thrive. Although it is prudent to keep only one of these fish per tank (unless you have a large tank and can acquire a pair), it can be kept with other angelfishes. While it tends not to be overly aggressive, it can hold its own with moderately pugnacious tankmates once it has fully acclimated, and it will rarely bother unrelated fishes. Adults attain lengths of 9-10 inches (25 cm) and will settle in quite well in a 150-gallon (376-L) or larger tank. The best advice is to resist buying a full-fledged adult. Juveniles are less stunning, but are much more likely to acclimate to your conditions and feeding. They begin to emerge from their dark, ugly-duckling camouflage age at a length of about 3.9 inches (10 cm).

To see even more images depicting the stunning members of the genus Chaetodontoplus, be sure to pick up a copy of the March/April 2018 edition of CORAL Magazine.

About the Author

Scott W. Michael is the author of Angelfishes and Butterflyfishes: Reef Fishes Book 3 (Microcosm/TFH) and other books,

References

Allen, G.R., R. Steene, and M. Allen. 1998. A Guide to Angelfishes and Butterflyfishes. Odyssey Publishing/Tropical Reef Research.

Arai, H. 1994. Spawning behavior and early ontogeny of a pomacanthid fish, Chaetodontoplus duboulayi, in an aquarium. Japan J Ichthyol 41: 181–87.

Debelius, H., H. Tanaka, and R.H. Kuiter. 2003. Angelfishes: A Comprehensive Guide to the Pomacanthidae. TMC Publishing, Chorleywood, UK.

Kuiter, R.H. 1990. A new species of angelfish (Pomacanthidae) Chaetodontoplus meridithi, from eastern Australia. Rev fr Aquariol Herpetol 16: 113–16.

Moyer, J.T. 1990. Social and reproductive behavior of Chaetodontoplus mesoleucus (Pomacanthidae) at Bantayan Island, Philippines. J Japan Ichthyol 36: 459–67.

Pyle, R.L. and J.E. Randall. 1994. A review of hybridization in marine angelfishes (Perciformes: Pomacanthidae). Environ Biol Fishes 41: 127–45.