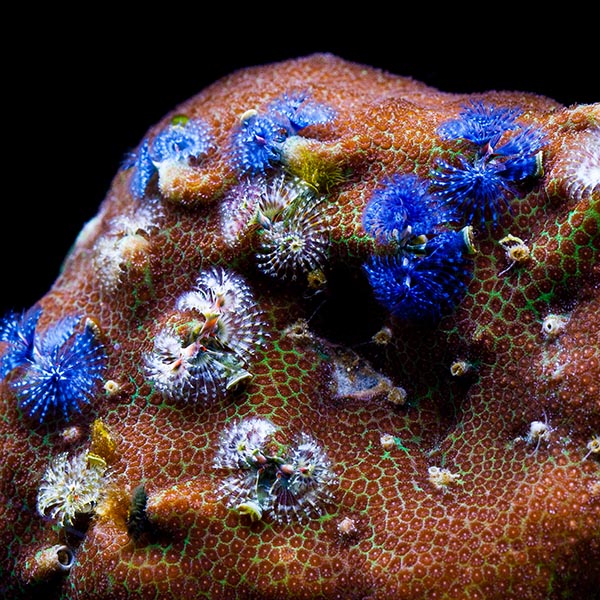

Very nice example of Bisma Worm rock seen in the aquarium trade. Image: Ben Clark.

Excerpt from CORAL, N/D 2017

By Than Thein

In the reef aquarium world, many aquarists call Spirobranchus worms either Bisma Worms or Christmas Tree Worms. These beautiful worms resemble feather duster worms or Coco Worms, but are smaller than either. They live embedded in hard substrate, usually the calcium carbonate skeletons of stony corals such as Porites or Cyphastrea.

A dual challenge

Commensal relationships on the reef are some of the most interesting facets of the saltwater hobby. These pairings add that extra bit of movement and complexity to the display tank. They are also a great way to start conversations with other aquarists and laypeople.

There is still some debate about the nature of the relationship between Spirobranchus worms and corals. It was once thought that the coral base helped feed the worms; the jury is still out on that. There is not much data showing that the worms consume any product of their coral hosts (Toonen 2002).

A more likely reason for this pairing is safety. It is possible that coral hosts are unappetizing to predators of Spirobranchus worms. Also, living coral grows over the worms’ growth tubes, and without that covering the worms are much more susceptible to predation. In the wild, it is uncommon to find Spirobranchus worms without a coral host. In captivity, however, these worms are able to survive even if their coral host dies.

At Tidal Gardens, we have one such colony whose base coral met an unfortunate demise. The worms continue to flourish. Whether or not the coral host is absolutely necessary for the survival of the worms is debatable; our experience may be a one-off. Many aquarists that have kept Spirobranchus worms in the past have not had success once their base coral died. Regardless, it appears that the worms prefer the presence of the coral, and we recommend that hobbyists looking to acquire Spirobranchus worm rocks care for both the worms and the coral.

Aquarium conditions

Determining the ideal aquarium conditions for bisma worm rocks can be a challenge; there are a variety of different corals the worms can colonize. For this reason, it is best to cater to the needs of the coral base. For example, the vast majority of worm rocks in the hobby are Porites, which tend to prefer a high lighting level and strong water motion. They are not as sensitive to chemical changes as other SPS, such as Acropora and Montipora, but it is always a good idea to keep your water chemistry as stable as possible and make sure there is plenty of calcium and alkalinity available to promote the stony coral’s growth.

On the other hand, Spirobranchus worms sometimes colonize a coral such as Cyphastrea, whose preferences are very different from those of Porites. Cyphastrea corals almost always prefer a dimly lit tank to a brightly lit tank. They are more tolerant of high nutrient levels, but they may struggle with sweeping chemical changes in the aquarium. Cyphastrea also require much less water movement than Porites, which are typically found in crashing surf zones.

In short, to determine the best aquarium conditions for your worms, look first for conditions favorable to the base coral.

Feeding the worms

Bisma worms use their spiral plumes for both feeding and respiration. Spirobranchus worms feed by trapping plankton and other small particles on the cilia in their plumes. The cilia then pass the food to the worm’s mouth.

It is difficult to specify the best food to feed because there are several different types of Spirobranchus worms, each with its own particular food preferences. The safest bet is to provide a variety of food. Here at Tidal Gardens, we try to feed our worms some of the cloudy supernate from thawing frozen food. The frozen food blend consists of krill, Mysis shrimp, rotifers, and CYCLOP-EEZE. Granted, large shrimps such as krill and Mysis are likely far too large for the small worms to consume, but the fine particles in the thawed supernate are the desired product. Krill and Mysis are very nutrient-dense foods.

Fish food manufacturers have developed dry plankton powder products designed for coral feeding. These may work, depending on the size of the particles and the type of plankton used in the preparation. In an attempt to cover all the bases, it is not a bad idea to incorporate a small amount of dry powder in with the frozen. As always, pay attention to the amount of food you are feeding. Overfeeding can lead to high nutrient levels, the consequences of which outweigh the benefits.

When administering food, a common mistake aquarists make is to spray the food right at the colony. Spirobranchus worms are skittish by nature. Even walking by the aquarium could spook them into retracting into their holes. Instead, direct the feed a few inches away from the colony. This allows the flow in the aquarium to carry the food to the worms. It is much less likely to frighten them and cause a hasty retreat.

The worms’ plumes have cilia that create their own mini water currents; these are not vortices that suck food and water toward the middle of the worm. The cilia move the water from the base and out from the middle. This can be seen when the worms defecate and effectively launch the waste out from the middle.

Conclusion

Spirobranchus worms and their host corals are a beautiful addition to a reef aquarium if the hobbyist is able to provide proper husbandry to keep them thriving. This is done by paying special attention to the needs of the base coral and feeding the worms regularly.

References

Toonen, R. 2002. Invertebrate Non-column: Christmas Tree Worms. Adv Aquar, http://www.advancedaquarist.com/2002/9/inverts.

Read the original, fully illustrated article in CORAL, November/December 2017, SYMBIOSIS Issue.

Thank you for your in-depth article about both the coral and the Bisma worms, for now I know they are both way beyond my capability to have them. I will enjoy the photos and leave the culture of them to others who are able to keep them successfully. I am saving your article to read over and over. Bless you very much!!!

buonasera volevo sapere se spedite in ITALIA GRAZIE

b