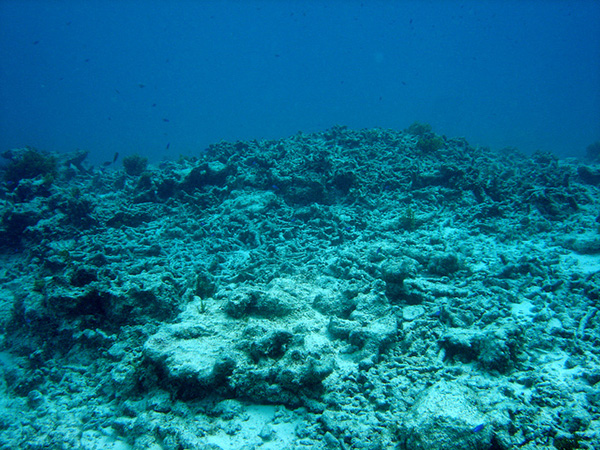

Coral bleaching in the Maldives in May 2016. Credit: The Ocean Agency / XL Catlin Seaview Survey / Richard Vevers.

Death by climate change?

The responsibility of climate-polluting countries to protect coral reefs

By Noni Austin

Earthjustice

Noni Austin, staff attorney with the Earthjustic International Program based in San Francisco.

Since 2014, a multi-year mass coral bleaching event has been killing corals around the world, including in World Heritage–listed coral reefs. Although this event is caused by climate change, climate-polluting nations that are custodians of coral reefs, such as the United States and Australia, are failing to do their fair share to reduce their contributions to climate change to protect reefs. Fortunately, the international community is taking notice of these failures, and the pressure on countries to take action on climate change continues to increase.

Growing up in Australia, I saw the full magnificence of the Great Barrier Reef before anyone had heard the term “coral bleaching.” When my parents took my brother and me to the islands, we found the beauty and diversity of corals and fish breathtaking. It is sobering to think that this vibrant underwater world could become just a memory within my lifetime.

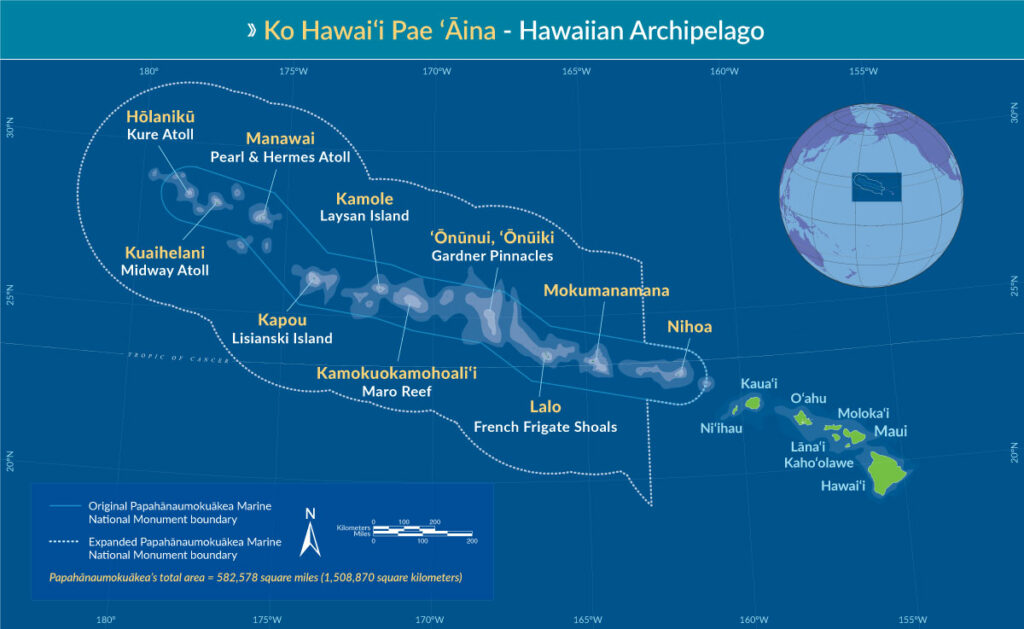

Over the past few years, the world has witnessed the bleaching and death of corals across the globe, triggered by elevated ocean temperatures caused by climate change. Many of the affected reefs are listed as World Heritage sites, including Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, Papahānaumokuākea in the United States, and reefs in Kiribati, New Caledonia, and the Seychelles. World Heritage sites are listed under the World Heritage Convention, a treaty signed by 193 countries to protect the world’s most remarkable places.

Healthy Indo-Pacific reef with Moorish Idols. Image: Rich Carey/Shutterstock.

Together with colleagues from Earthjustice, a non-profit environmental law organization based in the United States, I recently attended the annual meeting of the World Heritage Committee, which implements the World Heritage Convention. I was at the meeting in Krakow, Poland, alongside scientific experts and campaigners from Australia to inform the Committee of the serious threat posed by climate change to the very existence of coral reefs. We were also there to ask the Committee to advocate for stronger action by countries to reduce their contributions to climate change to protect coral reefs into the future.

Climate change and the global coral bleaching event

Coral reefs are telling us that climate change is happening now. The current mass bleaching event, which has bleached and killed corals around the world over the last three years, was triggered by elevated ocean temperatures caused by climate change. Climate change is fuelled by the emission of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, the largest source of which is the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas.

The impacts of this bleaching event are devastating. For example, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef – the world’s largest coral reef and one of its richest and most complex ecosystems—lost up to 50% of its corals in 2016 and 2017, the first recorded instance of back-to-back annual bleaching. Bleaching harms the entire reef ecosystem: the death of corals destroys the entire vibrant, biodiverse underwater world that provides vital breeding, nursery, and feeding grounds for thousands of species of marine life, as well as food, livelihoods, coastal protection, and other benefits to around half a billion people.

In addition to raising ocean temperatures, climate change increases the acidity of oceans, making it more difficult for corals and other marine animals to form skeletons and shells. It also causes stronger and more frequent storms that damage reef structures.

Bleached coral in New Caledonia to the east of Australia, photographed in March 2016 by The Ocean Agency / XL Catlin Seaview Survey / Richard Vevers.

Global action on climate change is essential for coral reefs to survive into the future

The scientific evidence is clear: Without an urgent and rapid global reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, coral reefs are unlikely to survive into the second part of this century.

In June of this year, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s World Heritage Centre (the secretariat of the World Heritage Committee) released the first global scientific assessment of the future impacts of climate change on the 29 reefs listed as World Heritage sites. The assessment was developed in collaboration with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch. Dr. Fanny Douvere, head of the Marine Programme at the World Heritage Centre and one of the scientific assessment’s lead authors, says, “The results of the assessment are sobering. Our work led us to conclude that all 29 listed reefs will cease to exist as functioning ecosystems by the end of the century without a substantial reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions. We found that if global emissions continue on their current trajectory (known as ‘business as usual’ emissions), within the next 20 years, many reefs will experience bleaching at a frequency that provides no opportunity for corals to recover, a process that typically takes 15 to 25 years.” For example, without drastic reductions in global emissions, Papahānaumokuākea and the Great Barrier Reef are predicted to experience bleaching twice per decade by 2029 and 2035, and annual bleaching by 2041 and 2044, respectively.

Although the situation is dire, Dr. Douvere notes that there is still hope. “The scientific assessment confirmed the conclusions of other scientists over a number of years: limiting global temperature rise to no more than 1.5°C (2.2ºF) above pre-industrial levels would give corals a chance of survival into the future.” This limit is the long-term goal of the parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s Paris Agreement. To achieve this goal, however, requires an urgent and significant reduction in global emissions, because even if all countries meet the current emissions-reduction targets that they have set for themselves under the Paris Agreement, we are currently on track for a temperature rise well beyond 3°C (5.5ºF).

Reef fishes in the Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Monument, Hawaiian Archipelago. Pennantfish, Pyramid, and Milletseed butterflyfish at Rapture Reef, French Frigate Shoals. Photo: James Watt

The role of the World Heritage Convention in protecting coral reefs

Earthjustice, headquartered in San Francisco, has been working with the World Heritage Committee and its advisers in recent years to protect World Heritage–listed coral reefs from the impacts of climate change. The Committee, which meets annually and makes detailed recommendations for protecting specific sites, is a powerful international legal tool. As Dr. Douvere says, the Committee “is highly respected, and its decisions do influence countries’ actions.”

At its meeting in July of this year, my colleagues and I spoke with the 21 national delegations to the Committee, urging them to issue a strong decision about the responsibilities of countries to protect coral reefs by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The final decision was powerful: the Committee expressed serious concern about the global bleaching event, and, for the first time, called on all countries to ambitiously implement the Paris Agreement to pursue efforts to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C and to undertake actions to address climate change.

This is an important step. It sets a clear objective that all countries must do their fair share to meet. It means that individual countries – and particularly those that are custodians of World Heritage–listed coral reefs – must step up and fulfill their responsibilities under the World Heritage Convention to reduce their contributions to climate change.

Degraded section of Great Barrier Reef following coral bleaching. Image: Nick Graham/ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

Unfortunately, countries like the United States and Australia, which have primary responsibility for protecting some of the world’s most incredible reefs, are failing to fulfill their international legal responsibilities under the World Heritage Convention to do their fair share to reduce their contributions to climate change. Although the United States is the largest historical emitter of greenhouse gases, it recently announced its intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement and to significantly weaken proposed regulations intended to reduce emissions from power generation (the largest source of emissions in the United States), and has lifted a moratorium on new coal leasing on federal lands. To make matters worse, the United States has initiated a review of Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Monument (along with over two dozen other national monuments and marine national monuments), with the possibility of removing some or all of its protected status.

Similarly, Australia’s emissions continue to rise, and it is unlikely to meet its targets under the Paris Agreement (targets that in any event do not represent its fair share of global emissions reductions). Australia is also strongly supporting the development of some of the largest new coal mines in the world, which produce emissions that would constitute a real and significant threat to the Great Barrier Reef for decades to come.

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, a huge reef and island tract in the Hawaiian Archipelago: Threatened with loss of its protections as a U.S. National Marine Monument by a new U.S. government administration in Washington.

The failure of countries like the United States and Australia to reduce their emissions not only damages their own reefs, but it also damages reefs in countries that have negligible greenhouse gas emissions, like the Seychelles and Kiribati.

If well-resourced countries responsible for significant emissions were committed to protecting coral reefs, they would engage in a rapid and just transition to renewable energy, remove their support for fossil fuels, and meet and strengthen their emissions-reduction targets under the Paris Agreement.

Obviously these actions alone will not protect coral reefs. But they would be a significant step towards reducing emissions, and they would increase the political pressure on other countries to take stronger action on climate change.

Preventing death by climate change

To ensure that coral reefs survive into the second half of this century, humanity must substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Big polluting countries, especially those such as the United States and Australia that are responsible for protecting coral reefs within their territory for the benefit of all humankind, must do their fair share to reduce their contributions to climate change. Together with my Earthjustice colleagues, and concerned scientists and citizens from around the world, I look forward to continuing to advocate for the World Heritage Committee to hold countries accountable for failing to do their fair share to reduce their contributions to climate change to protect coral reefs.

Noni Austin

Staff Attorney – International Program

Earthjustice

Noni Austin is an international environmental lawyer at Earthjustice, the largest non-profit environmental law organization in the United States. An Australian and U.S. lawyer, Noni works with communities, organizations, and indigenous groups to develop and implement legal strategies to combat climate change, protect the environment, and defend the rights of all peoples to a clean and healthy environment

TAKE ACTION