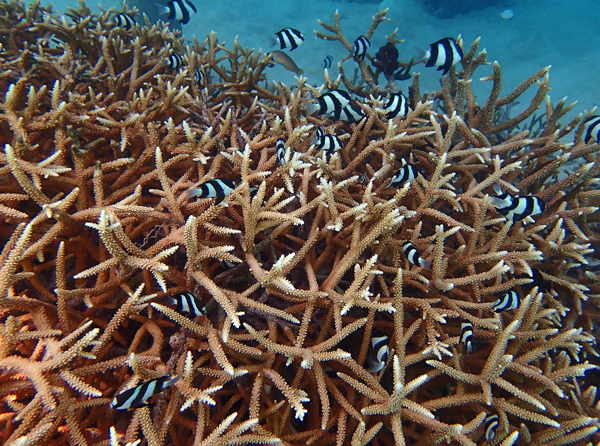

Humbug dascyllus (Dasycllus aruanus) in a healthy staghorn coral (Acropora grandis) thicket.

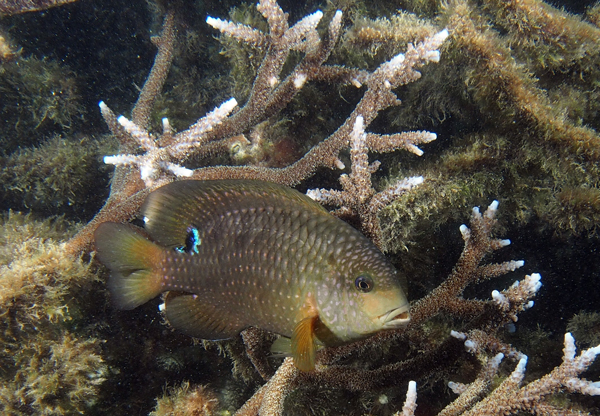

Humbug dascyllus among a collapsing dead staghorn Acropora colony killed in a mass bleaching event in the Maldives islands in the spring of 2016.

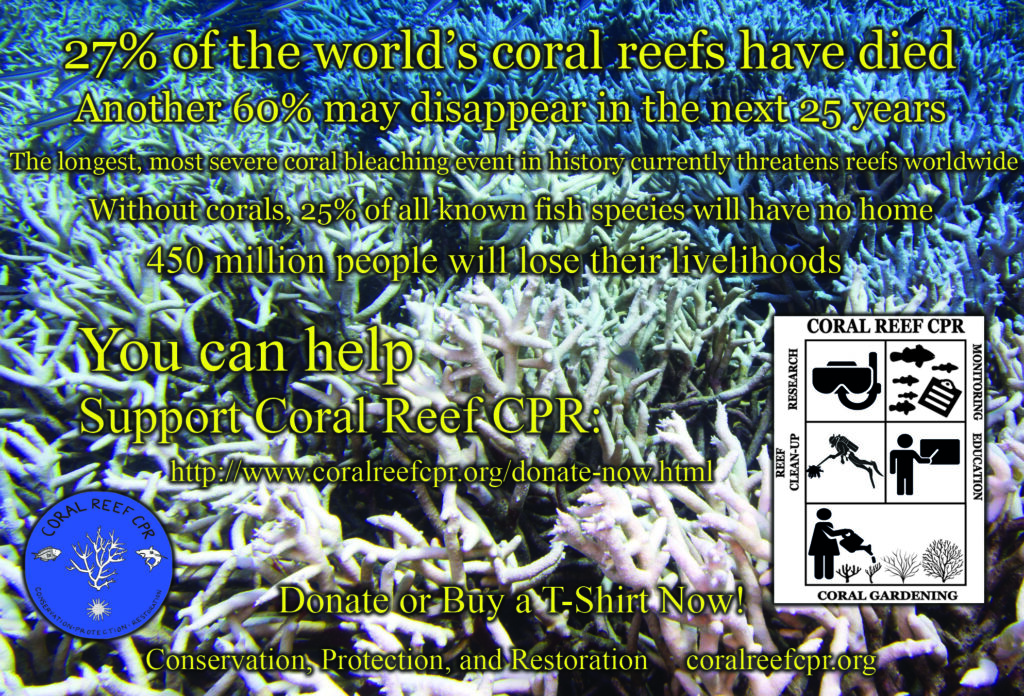

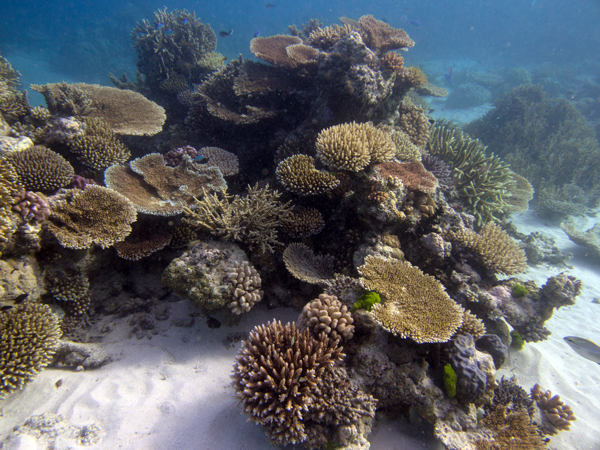

Preventing the collapse of the coral canopy and loss of reef fishes through coral restoration in the aftermath of mass bleaching in the Maldives in 2016, when most Acropora corals died

By Andrew Bruckner and Georgia Coward

Coral Reef CPR

Georgia Coward

Andrew Bruckner, PhD

Corals are the forests of the reef, providing complex, high relief structure that is home to millions of reef fishes, motile invertebrates and algae. Most reef-building corals form elaborate colonies consisting of thousands of interconnected polyps arranged in a diverse array of shapes and colors. These corals are the reef’s building blocks, creating essential habitat used by fish as nurseries, shelter, resting grounds and feeding areas. The acroporids are among the most important, diverse, and abundant corals, with over 150 different species worldwide and at least 49 species in the Maldives.

Their fast growth and successful reproductive strategies have allowed them to dominate both intertidal and subtidal habitats, forming fields of staghorn-like branches, shingle-like tables, bushes, tall columns, stout fingers, and crusts that once covered 50-90% of the reef substrate. Yet, they are also the most sensitive and vulnerable to temperature perturbations, predation, storm damage, diseases, and bleaching, as well as other stressors. During the mass bleaching event in the Maldives in April and May 2016, more than 80% of the acroporids died, and the survivors are now under attack by two voracious corallivores: Crown of Thorns Starfish (Acanthaster) and coral-eating “Drupe” snails (Drupella spp.).

Bumphead parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum) headshot showing the fused parrot-like beak.

The loss of Acropora is a catastrophic event for reefs. It has both immediate and cascading future impacts and is especially bad news for reef fish and the motile invertebrates that depend on healthy corals. Globally, there are around 130 species of fishes that are corallivores, some of which only eat coral and others that consume coral tissue and other resources. About half of these are the charismatic, colorful butterflyfishes, but many other corallivores, including certain wrasse, triggerfish, and filefish families compete for coral as an important food resource. Through intense competition, many have evolved highly specialized feeding strategies – some are polyp-feeders, others feed only on coral mucus, and a few eat the tissue as well as the underlying skeleton. Polyp feeders have a long, snout-like mouth that allows them to remove individual coral polyps without damaging the skeleton. The Tubelip Wrasse (Labrichthys unilineatus) and other mucous-feeders can obtain their nutritional requirements without killing any coral polyps.

Reticulated Butterflyfish (Chaetodon reticulatus) is a specialized corallivore, eating only live coral polyps.

Stony Corals: Sustenance & Shelter

There are fish species that only eat coral, as well as many facultative corallivores that switch to sponges, tunicates, and other food sources if their preferred coral disappears. Certain fish, such as the Chevron Butterflyfish (Chaetodon trifascialis), are so specialized that it only eats a single coral species, Acropora hyacinthus. Parrotfish and other larger-bodied herbivores feed primarily on turf algae surrounding the corals, but they also eat coral, excavating the skeleton as they feed. Parrotfish leave telltale signs on their coral host—scrape marks that are a perfect impression of their fused, parrot-like beak—and their feeding can often be heard by divers. Many of the obligate corallivores, as well as some of the larger coral-eating species, influence the distribution, abundance, and community composition of corals through their feeding behaviors. Most notable among these is the Bumphead Parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum), who consumes over 13.5 kg of live coral within a square meter each year, and produces more than 5 tonnes of sand.

Trapezia crab defending a Pocillopora coral from corallivores

The corals serve many other non-replaceable functions for reef fish. Some fish feed on the polychaetes, crabs, shrimp, and molluscs that live within the branches of the corals, and many of these invertebrates will disappear if the coral dies. Certain territorial damselfish are known as farmer fish; they bite at the coral branches to create space for the growth of fine filamentous algae, which they tend for food and vigorously defend from other herbivores. Hundreds of reef fish species also settle onto the reef, near or within live coral, after spending their larval phase in the water column. Even juveniles of species that are not coral dependent as adults will live among the coral, and they actively avoid settling near dead coral. Smaller plankton-feeding reef fish, such as certain gobies and damselfish, take refuge among live coral, moving up into the water column when it is safe to feed on plankton. If the corals they inhabit bleach or die, they tend to be more susceptible to predation, possibly because the living coral may help camouflage the resident fishes while offering protection from its stinging cells.

The Citron Goby (Gobiodon citrinus) has been extirpated from many reefs in the Maldives in the past year.

Disappearing Fishes

Since May, we’ve witnessed lower numbers of butterflyfishes and the near complete disappearance of other fishes, such as the Coral Goby, from areas that lost all of their Acropora. Most of the other reef-associated fishes have remained, mainly because the severe coral bleaching in 2016 did not result in immediate loss of habitat. The corals died, but their skeletons have remained intact, and unless there is a bad storm, many of the graveyards of the robust skeletons, such as the table corals, should persist for a few more years until erosion takes its toll.

The Farming Damselfish (Stegastes punctatus) gardens and defends its preferred algae among Acropora thickets.

A patch reef displaying the high structure provided by different species of Acropora.

Dead coral habitat that has retained its structural complexity can continue to support abundant and diverse reef-fish communities, but the physical degradation of the coral skeletons reduces both the complexity of the reef environment and the three-dimensional space on that reef. This triggers increased competition for both food and prime refuge sites, and reef inhabitants are at a substantially greater risk of being eaten. Once this structure provided by the coral skeletons collapses, both the abundance and diversity of reef fish will decline by as much as two-thirds.

A Coral Reef CPR scientist establishing a coral restoration plot in the Maldives. Coral frags will grow into place on rock, and nails will eventually rust away.

Holistic Reef Restoration

Through Coral Reef CPR’s Holistic Approach to Reef Protection (HARP) Program, we have now established coral nurseries in eight locations on two atolls. Our efforts are focusing on the acroporids, mainly because they sustained the greatest losses and their death has left entire reef habitats devoid of living coral. We have found bleaching refuges that still contain Acropora, largely intact. We will closely monitor these this year during February and March to determine if they reproduce during their annual mass spawning event, helping speed up the recovery of endangered Acropora populations through the settlement of new coral larvae. We have created small restoration plots on low-relief hard bottom areas that lost all their coral by attaching small fragments to the bottom with nails (which quickly rust and disappear after the coral fragment has naturally fused) and cable ties.

We are also growing 26 species of Acropora in our rope and table nurseries using detached and broken branches that were found littering the bottom, as well as coral collected from construction and dredging sites and branches clipped from colonies with disease and predation scars from Drupella snails and Crown of Thorns Starfish. By February of 2018, we will begin replanting larger nursery-grown colonies on the reef, placing like species in breeding clusters to maximize their ability to reproduce and further facilitate recovery of corals from the devastating impacts of 2016.

You can follow our progress and adopt one of our coral nursery fragments or ropes online at coralreefcpr.org.

Contact

Coral Reef CPR