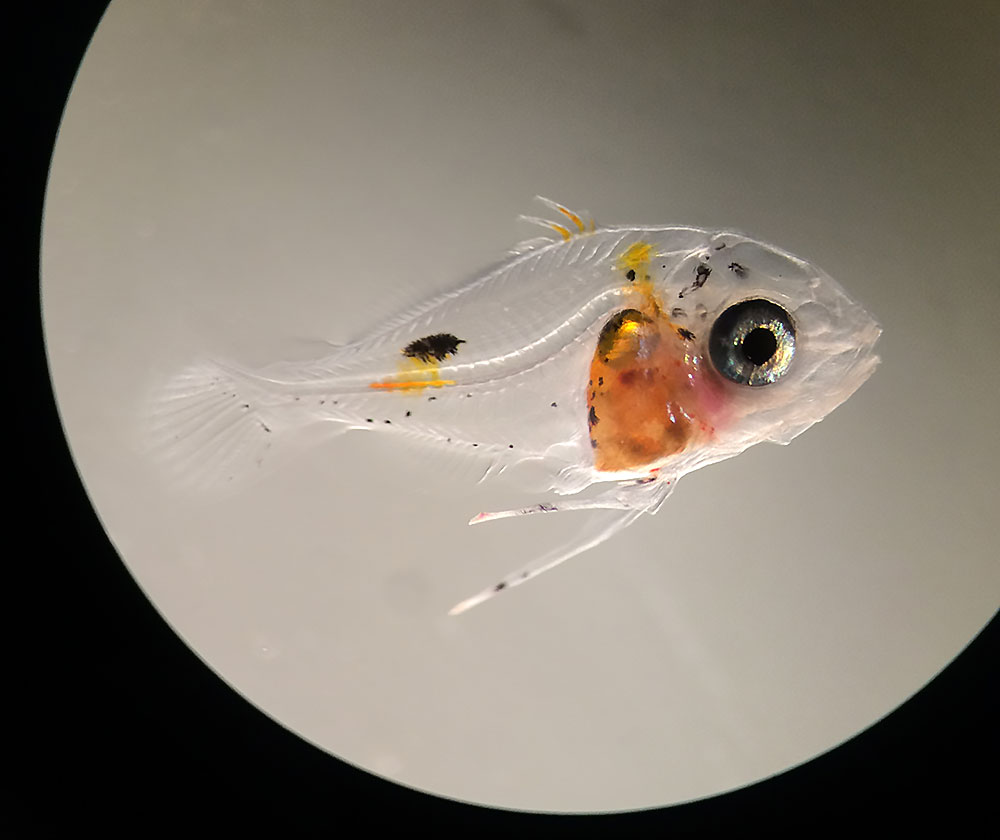

Groundbreaking captive-bred Blue Reef Chromis, Chromis cyanea, bred in 2016 at the New England Aquarium

First Successful Breeding of the Blue Reef Chromis, Chromis cyanea

An exclusive online bonus article from CORAL Magazine

By Monika Schmück

Chromis cyanea, the Caribbean Blue Chromis, is a dynamic and popular reef fish that adds color and movement to many public aquaria exhibits across the country, including the New England Aquarium (NEAq) in Boston, Massachusetts.

At any given time, NEAq’s largest exhibit, the Giant Ocean Tank, will hold a school of up to 100 Blue Chromis. So it was no surprise that, when the NEAq initiated an official larval rearing program to expand on their sustainability efforts, the focus was decidedly on a key exhibit species, the Blue Chromis.

Early in 2015, the New England Aquarium acquired a small school of 20 wild-caught Blue Chromis to serve as the broodstock population. As the Lead Aquarist of the NEAq’s Larval Program, I immediately began grooming the population for breeding using nutrition, lighting schedules, and water temperature. The fish were started on a varied diet of small items such as frozen Mysis and Capelin eggs, fed five times per day to satiation.

Over the course of four weeks, the population was transitioned to a 14-hour lighting schedule and a water temperature of 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The salinity was kept between 32 and 34 ppt. Exactly two weeks after the lighting schedule was set, the chromis laid their first nests along the substrate!

With many years of experience in holding and quarantining Blue Chromis, my fellow aquarists knew that these reef fish, like many damselfishes, are not as peaceful as they may seem. They are very territorial, and when held in close quarters with conspecifics, they will fight and chase each other incessantly.

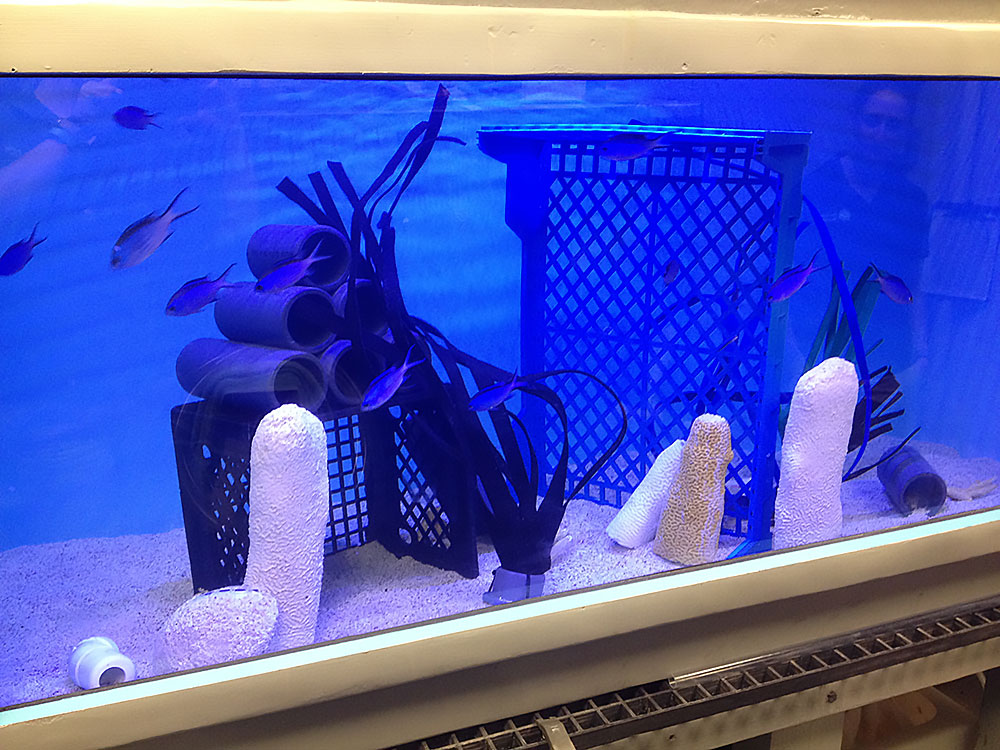

Fish Feng Shui

We kept this in mind as we assembled the 500-gallon system to house the entire broodstock population, employing pieces of habitat we commonly use in our holding tanks, such as milk crates and pyramids of PVC pipe, to divide up the space and create visual barriers – basically like fish feng shui! The bottom of the tank was covered with 200 lbs of CaribSea Aragonite Flamingo Reef Sand as suitable nest-laying material. A small population of Neon Gobies (Elacatinus oceanops) was also added as cohabitants to provide cleaning and “stress reduction” services to the chromis.

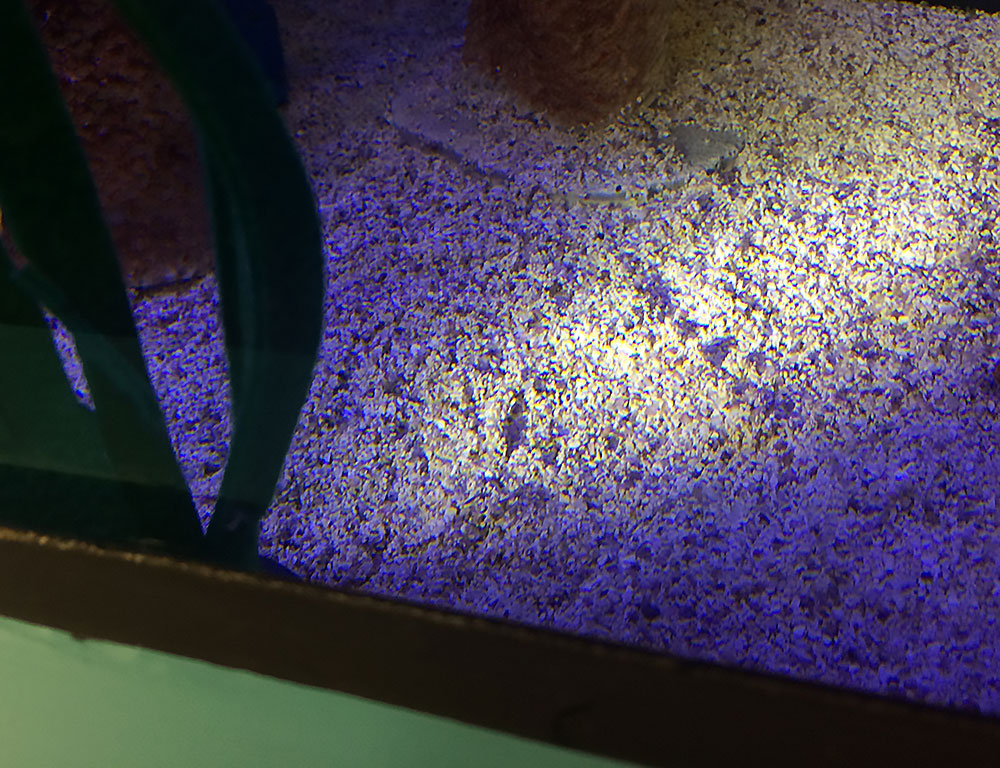

Soon after I became proficient at spotting the telltale substrate clumps that result from the deposition of tiny, sticky eggs, I learned to recognize the Blue Chromis’ courting behaviors. I could then anticipate and prepare for a nest.

The males will groom their territory by brushing their tail along the substrate and nipping at out-of-place bits with their mouths. To attract a female, they will turn a bright blue and perform a lateral display or sometimes exhibit countershading with half navy and half light blue colors, coupled with a swimming behavior where they dip up and down in front of her. Once the female is persuaded, she’ll scoot along the nest site and lay her eggs, and the male will swoop down after her and fertilize them. The female will then leave and the male will be left to clean, aerate, and protect the nest.

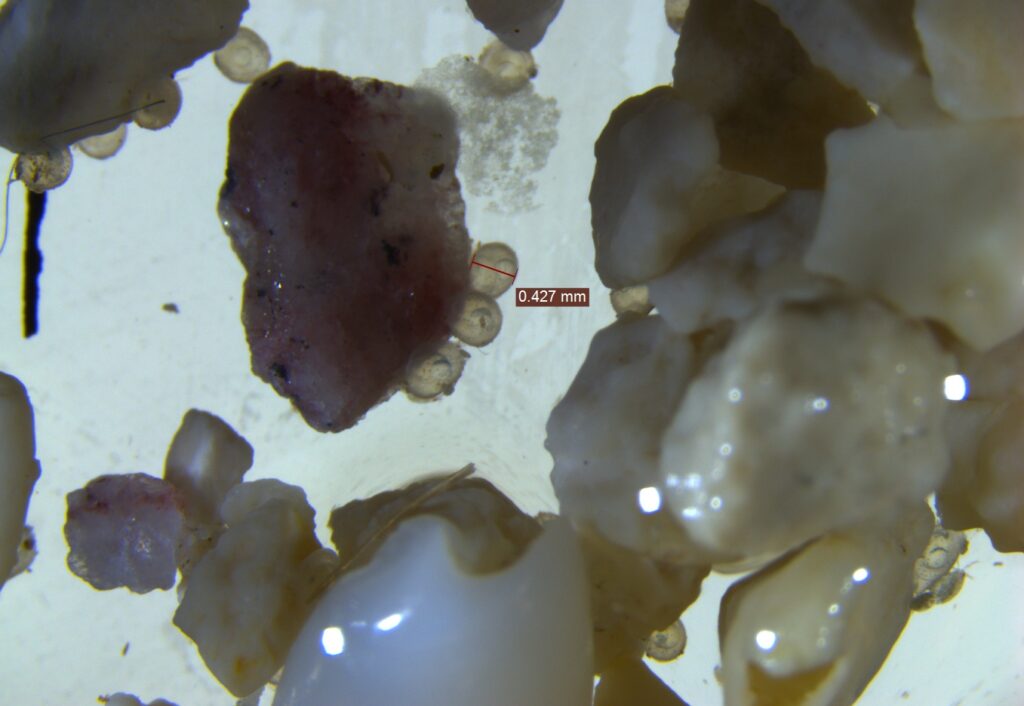

Two days after the nest is laid, the swath of substrate is carefully siphoned from the broodstock tank, disinfected, and placed in a temporary hatching tank connected to the rearing system. Using a temporary tank for hatching eliminates the introduction of substrate, and anything living in it, into the rearing system.

Typically, by the next day, thousands of 1-mm-long larvae have hatched, and I manually transfer them to the rearing tanks. I have attempted rearing Blue Chromis larvae in two different rearing systems – one system consists of three 65-liter black round tanks, and the other has two 130-liter black round tanks. The larger 130-liter tanks, as expected, have the space capacity to hold higher numbers of larvae as they grow. Success with rearing Blue Chromis in the smaller tanks can probably be attributed to a higher concentration of food, and thus a higher prey-encounter rate. Both systems are generally kept around 78 degrees Fahrenheit, with salinity readings between 34 and 35 ppt.

The larval rearing system used to produce the first captive-bred Blue Reef Chromis: 65-liter tubs above, and 130-liter larval rearing tubs below.

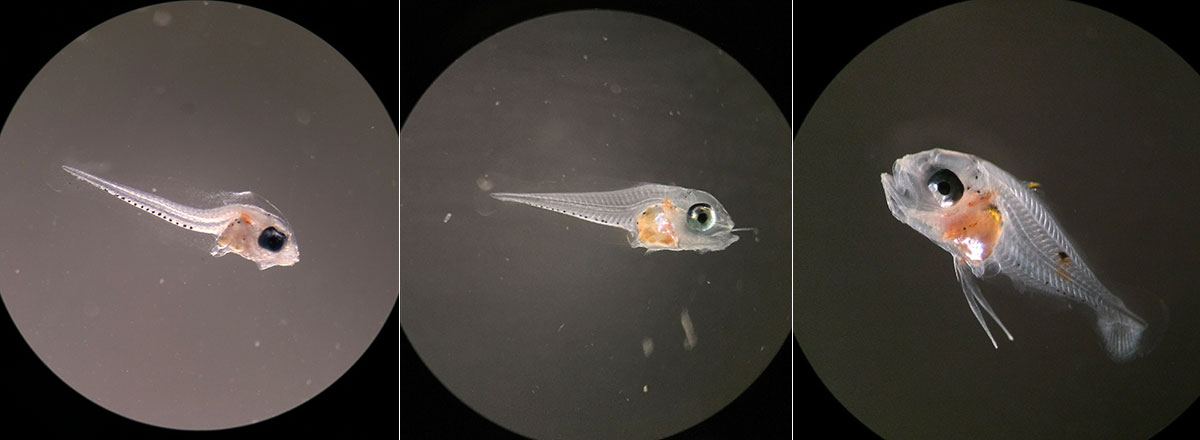

Blue Chromis larvae are very small and underdeveloped when they hatch, living off of their yolk reserve for the first 48 hours. As the yolk shrinks, they start to develop large eyes and mouths in preparation for catching live prey.

The pre-feeding stage of a larval Blue Reef Chromis, Chromis cyanea, here shown at 0 days post-hatch (dph) at left, 1 dph center, and 2 dph right.

When they approach first feeding, I begin the daily routine of offering an abundance of common food types: Parvocalanus crassirostris and Pseudodiaptomus pelagicus copepods and Brachionus rotundiformis rotifers. Phytoplankton species, Isochrysis galbana and Tisochrysis lutea*, are added to the feeding regimen to feed the zooplankton and cloud out the rearing tank, which helps the larvae easily seek out their prey. Throughout the entire rearing process, the larvae require relatively high air flow and high turnover rates, which can prove to be a balancing act when trying to retain a phytoplankton bloom. The rearing tanks are also lit with LED strip lights for 24 hours a day.

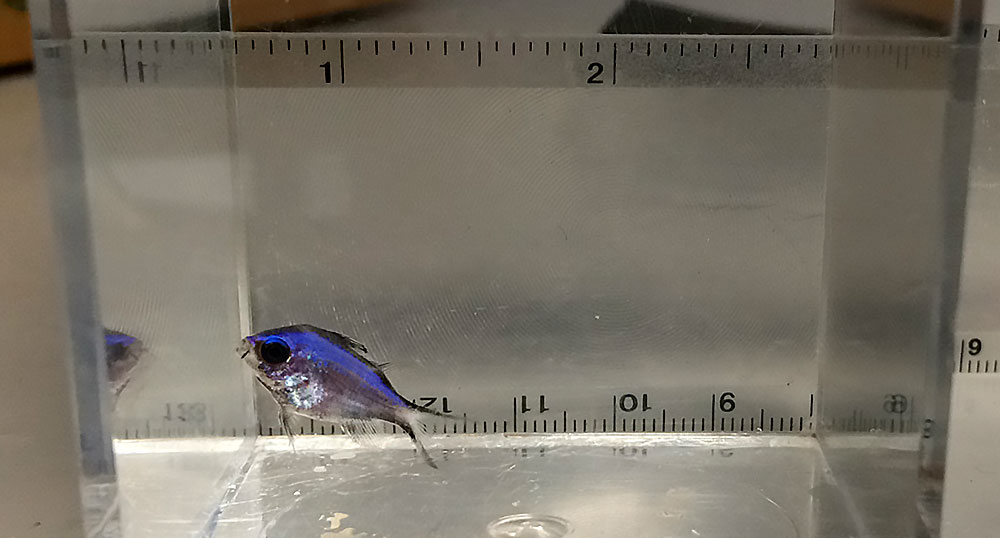

Over 11 months, the Blue Chromis broodstock laid multiple nests two to three times each month. Out of those nests, about 80% of them were removed for an attempt at rearing, and 100% of those rearing attempts were unsuccessful past 23 days post-hatch (dph). In May 2016, one particular rearing attempt started out like all of the other previous attempts: there was a fairly high rate of mortality within the first two weeks of growth, then around 15 dph, the larvae started to develop their long pelvic fins.

Early larval development of the Blue Reef Chromis, Chromis cyanea, shown here left to right: 9 dph, 12 dph, 17 dph.

Up until this point, only one larva had made it to flexion. But this time, flexion began on day 20.

Surprisingly, ten days later, when flexion was complete, 26 larvae still remained! Unfortunately, with no obvious explanation, the numbers continued to dwindle after flexion, and by day 40 a mere 4 larvae remained.

When they reached 44 dph, the larvae had started to gain some of their classic blue hue, and at 63 dph, the smallest and least-developed larva died, leaving a total of 3 larvae. It wasn’t until a long-awaited 85 dph before the first larva finally reached the juvenile stage, losing the long pelvic fins and gaining full blue coloration, black fin markings, and a forked tail. Aggression towards smaller conspecifics immediately ensued, resulting in the loss of one and the separation of the other two. In total, only two Blue Chromis have made it through.

One of the world’s first captive-bred Blue Reef Chromis, Chromis cyanea, shown here only a couple weeks past settlement and metamorphosis at 100 dph.

There is still a great deal of research to be done on refining rearing techniques, identifying feeding preferences, and decreasing time to settlement. I look forward to continuing to work with this species in hopes of someday achieving a school of Blue Chromis, reared in-house, on exhibit at the New England Aquarium!

Update

Since Schmück initially authored this article, we’re delighted to report that a second batch of offspring has now been reared, and time to settlement has been improved upon. We’ll include any further details relayed as they become available! As relayed by Schmück on January 6th, 2017:

“I started offering 1st instar Artemia (at 38 dph) and pellets (at 49 dph) earlier, but the larvae already appeared larger which is why I opted to feed them larger items. I also increased the overall airflow throughout the entire rearing process and offered S-type rotifers for a longer period. I was able to get 10 total larvae through to complete settlement this time!”

*Editor’s note – Tisochrysis lutea is the scientific name that has been given to the phytoplankton strain formerly and commonly known to aquaculturists and marine fish breeders simply as T-Iso, or Tahitian Isochrysis. Read the description of Tisochrysis lutea here.

About The Author

Monika Schmück has worked at the New England Aquarium for 6 years and is currently the Lead Aquarist at the aquarium’s offsite facility, the Animal Care Center, in Quincy, MA. Schmück’s main focus is larval rearing and live foods culturing. Her love for plankton and everything larval started in a freshwater zooplankton lab at the University of New Hampshire, where she graduated with a BS in Marine and Freshwater Biology.

Glad to see more and more species being captive bred.

These are common on my offshore farm, where no collecting is allowed. Glad to see your worthy efforts bearing fruit.

Well done, Monica! The GOT will look spectacular with these additions!