The Yellow Longnose Butterlyfish, Forcipiger flavissimus, is one of the “bread and butterflies” still readily available in the aquarium trade, and generally seems to settle into captivity well.

Finding and Purchasing Butterflyfish

An online bonus for the September/October 2016 issue of CORAL Magazine

by Matt Pedersen

Back in the day, butterflyfish were more popular, but with the advent of reef aquaria, they have largely fallen out of favor. It seems US-based importers and wholesalers have narrowed the range of what they offer to primarily proven, bread-and-butter species, or those species prized for certain biological roles they can play in a reef. Arguably stealing the show these days are the various species from the subgenus Roaps (Chaetodon burgesii, C. declevis, C. flavocoronatus, C. mitratus, and C. tinkeri), which are generally thought of as being reef-safe. However, most of these are difficult to find at best, and all carry a higher price tag than most “bread and butterflies.”

More routinely offered, the often difficult Copperbands (Chelmon rostratus) and nearly bulletproof Klein’s Butterflyfishes (Chaetodon kleini) are kept around for their Aiptasia-controlling reputations, whereas Long-nosed (Focipiger flavissimus), Black & White Heniochus (Heniochus acuminatus), Auriga (Chaetodon auriga), Pearlscale (C. xanthurus), Double Saddle (C. ulietensis), Punctato (C. punctatofasciatus), and Raccoon Butterflies (C. lunula) seem to be some of the “classic” “betterflies” that are persistently offered and best suited to FOWLR-type aquariums (yes, there are probably a dozen additional species that are available less frequently, some of which aren’t nearly as agreeable to captive conditions, while other uncommon offerings can fare well, including prized Red Sea species like C. semilarvatus).

The Yellow Pyramid Butterflyfish (Hemitaurichthys polylepis) and the related but less common Zoster Butterflyfish (H. zoster) have become more popular in recent years; their reputation is that they are “reef-safe” Butterflyfish.

Our native Butterflyfish from Florida (C. capistratus, C. striatus, C. sedentarius, and C. ocellatus) are available with some regularity due to proximity, although they can be challenging at times (C. sedentarius has a reputation as the best to try). It seems that the Eastern Pacific Banded or Three-banded Butterflyfish from Mexico (C. humeralis, a sibling species of C. striatus) is now showing up somewhat routinely. I’ve personally used both the Banded Butterflyfish (C. striatus) and Foureye Butterflyfish (C. capistratus) in reef settings for Aiptasia control with extremely positive results, watching them leave SPS and even some LPS alone; still, these two species would be reef-safe “with strong caution” in my book (I owe Mike Meadows of The Coral Shoppe in Ohio for tipping me off to the reef potential of C. striatus).

Chaetodon capistratus, the Foureye Butterflyfish, is a US native often available outside of Florida. It destroys Aiptasia, but has a mixed reputation in terms of its ability to transition to prepared aquarium feeds. I’ve found extremely good success offering live California Blackworms as a first feed for this species, and the few that failed to accept those eagerly accepted live Canadian-farmed mussels on the half shell.

Beyond the Bread and Butterflies

If the species of Butterflyfish you seek is not reef-safe, not hardy, not easy to feed, or doesn’t perform a special beneficial behavioral service in your tank, odds are it can be difficult to find the species you’re looking for. Many of the poor Butterflyfish choices are not as common as they once were in the trade; as an outsider, it seems that they got the message to largely avoid those species that fail to thrive or have specialized dietary requirements. Some formerly common but poor choice Butterflyfishes are so hard to get, even on special request, that I might call them “book fish,” a term generally reserved for actually-rare fishes.

Chaetodon meyeri, an obligate coralivore, and a rare find in the aquarium trade, shown here in a quarantine tank that was ready to receive it. According to AquariumTradeData.org, just 137 were imported to the US in 2011. Despite some initial success with feeding, this fish was lost to a bacterial mouth rot that occurred during quarantine. Ironically, the fish had been successfully treated for Cryptocaryon prior. This species remains on the “expert only” or even “glutton for punishment” list, and should be avoided by most aquarists until its husbandry secrets are unlocked.

If you want to obtain a difficult-to-find species, the first advice I’d offer applies to the pursuit of any rare fish: do your research, set aside the ample funds to finance the purchase, and get the quarantine tank up and running now. That way, whether the fish shows up tomorrow or two years from now, you’re ready to accept it.

Butterflyfishes are not very tolerant of each other, so individual quarantine may be best. This could mean individual 10-20–gallon stand-alone tanks (most of these fishes are sold in the 2-4” range, where this would be appropriate), or a larger aquarium divided into sections to isolate individual fish. Sections of PVC fittings at various sizes can be used to provide shelter/cover; many new Butterflyfishes are skittish and shy when initially settling in. Butterflies are consummate grazers and pickers, so we might suggest adding some extra live rock to the QT tank. Heck, if has Aiptasia on it, even better.

If you’re lucky enough to purchase your Butterflyfish from a local fish shop, take the opportunity to assess it before buying. All the standard advice comes into play here. Pay very close attention to the health of the fish, look for any signs of parasitic problems, rapid breathing, cloudy eyes, ragged fins, or red mouths; learn what to avoid. Watch how it’s interacting with any other tankmates. Ask to see the fish eat, and avoid emaciated specimens. All that said, I’m personally inclined to think that if you’re looking at species known to be challenging, getting it “fresh” and getting it home fast may at times be better than the classic advice of asking the LFS to hold it and waiting to see how it does. If you’re special-ordering something, it’s better to just get there immediately when it arrives and take it home, avoiding your LFS tanks altogether. I do believe there is some merit to the notion that when you only have one or two new fish to look after, it is you, the final aquarist, who can pay more attention to that individual fish.

With challenging species, I in no way intend to slight the LFS; I simply believe experienced aquarists *might* have the edge over general LFS staff whose attention is spread over an entire store. So you’ll need to make a calculated risk and an educated choice. If you shop online, some vendors do keep challenging or rare Butterflyfishes available but out of stock, allowing you to select for in-stock notifications. When the fish show up, don’t wait, pull the trigger. Again, the key here is to get the fish to its final destination quickly.

Success with Butterflyfish is far more likely with juveniles. Large, showy adults make impressive displays, but when brought in as adults they tend to fare poorly, even if it is generally a solid species.

A shipment of juvenile Foureye Butterflyfish, around 1.5 to 2″ in length each, is unpacked and ready for drip acclimation. Despite this species’ reputation, all transitioned well onto aquarium foods given enough time, an experience that strongly reinforces the advice that younger Butterflyfish make better choices than mature specimens.

Quarantine for Your New Butterflyfish

Butterflyfishes are prone to ectoparasite problems. Some aquarists choose to perform an immediate FW dip upon arrival; others may choose a medicated dip protocol (Blue Life’s Safety Stop combines courses of Methylene Blue and Formalin for a quick one-two punch).

In the current CORAL Magazine issue devoted to Butterflyfishes, Bob Fenner recommends that aquarists forego quarantine, suggesting, “It’s far better in almost all cases to put these species through a pH-adjusted freshwater bath, with adjuncts ranging from methylene blue (very safe) to formalin (toxic to all), and place them immediately in their well-established permanent display system.” Of course, Bob is quick to note that there cannot be any “established bullying livestock in place…and that your Butterflyfish is in good initial health.”

I completely understand Fenner’s point of view: being able to pick at live rock and have the large tank to settle into afford the Butterflyfish every chance at success. I’ve applied this thinking to multiple Butterflyfishes coming from good sources, but in most cases, I wound up causing an outbreak of Cryptocaryon in the reef, and would wind up pulling out the fish for treatment in a hospital tank. So, based on personal experience, I take a more cautious approach.

Prophylatic treatment of all new Butterflyfishes is something I’m inclined to recommend; a full course of a copper-based medication (I personally like Cupramine) is generally my starting point to handle the Crytopcaryon and Amyloodinium these fish seem so prone to contracting; this is another area where Fenner and I differ in practice, and Fenner is wise to point out that the Chaetodontids “shies on the side of easy copper toxicity, so if you plan to try cupric administration, do keep dosings on the low side (0.20 ppm free copper or equivalent) and test at least twice daily for concentrations”.

Indeed, be sure to test copper levels and monitor closely; if you’re using live rock in the QT tank, it may react with copper levels (also, remember to not later use this rock in your reef tank, should it wind up leaching copper back into the system). After cleanup and removal of copper (water changes, carbon, Cuprisorb, Poly Filter pads), a subsequent course of treatment with praziquantal (easily obtained as PraziPro) can further de-worm the fish and kill any flukes not affected by the copper. Even if you adopt a more passive reactionary approach to fish mediation, copper and praziquantal are two standards that I think any butterflyfish enthusiast should have at the ready. Fenner also suggests, “Alternately, quinine compounds (quinacrine hydrocloride, chloroquin diphsphate) can be efficacious and less outright toxic.” I have recently personally added Acryflavin to my medicine chest, finding it effective against some infections that appeared to be Uronema, and another suitable alternative to try against common protozoan maladies.

The Butterflyfish Achilles Heel—Feeding

Experienced aquarists are generally able to manage, if not predict and prevent, most marine maladies. Despite the predisposition to disease in many Butterflyfishes, it is in fact feeding that I believe prevents the greater challenge with most species.

Feeding new Butterflyfishes can be tricky if they’re not one of the easy-to-keep “betterflies.” Live feeds tend to get the fish over the hump if they’re hesitant. Live adult brine shrimp can be a good choice; it should be enriched before feeding. Live California Blackworms have proven to be an exceptional starting food for certain species of Butterflyfish. The downside is that they die within minutes of being added to the aquarium, and if not immediately consumed, should be removed. Fresh live clams, scallops, and mussels on the half shell can entice recalcitrant feeders and are often available through your local grocery story; these too can foul quickly. Corallivores are extremely tricky, and despite my showing a few images of them here and in our current CORAL issue, I’d strongly discourage you from trying them unless you truly have decades of experience under your belt; I’m still definitely failing more than succeeding with them. Even the tank-raised specimens that become available are still quite sensitive and demanding in their care requirements.

Frequent feedings are key for Butterflyfishes; they are used to feeding throughout the day, so don’t expect them to flourish on light, once-a-day offerings. Frozen foods are generally good offerings, but if you can get them to eat pellet feeds, even better. Pellets that sink are ideal, but present husbandry problems in tanks with strong currents that blow pellets away, or coarse substrates that allow pellets to be lost into the sand. Fine sand and the use of “feeding modes” on circulation pumps can help counter these problems.

Pellet size is often an issue for Butterflyfishes, so try smaller sizes than you might anticipate for a fish of their size. If you can get them transitioned over to pellet foods, the use of an automatic dry-food feeder a few times per day can supplement the feeding you do, and really help keep the weight on your fish. I’ve found the use of a feeding ring or feeding tube below the automatic feeder to be very helpful in preventing pellets from being simply skimmed from the surface and into the filtration. Feeding remains a crucial part of Butterflyfish success; a robust, healthy fish is far less likely to crash out on you, and individual specimens are known to live well over a decade in captivity.

Another Butterflyfish species on the “do not buy” / “expert only” lists due to its corallivore status, this tank-raised Chaetodon trifascialis has done well on pellet foods for several months, but lost considerable weight during a 10-day vacation where it was fed only once daily. Recovery came over the course of a month with the use of an automatic feeder scheduled to feed eight times daily.

Want More? Buy These Issues for Your Personal Library.

If you’re contemplating a Butterflyfish Revival of your own, and want to know more, check out our coverage in CORAL Magazine, including:

- Butterflyfish were a cover feature back in our November/December 2009 issue of CORAL Magazine, with contributions from Daniel Knop (Butterflyfishes), Inken Krause (Butterflyfishes (Chaetodontidae) and their systematics, and Butterflyfishes in the Sea and in the Aquarium), and Ellen Thaler (Butterflyfishes and their Aquarium Maintenance). Our print edition back issues are sold out, but you can still purchase this issue as a digital download.

- Available Now: The September/October 2016 issue of CORAL Magazine, BUTTERFLIES, including an extensive survey of the species in A Rabble Of Butterflyfishes by Robert M. Fenner (Bob Fenner), and a look at the cutting edge of Butterflyfish husbandry and propagation in Butterfly Challenges by Matt Pedersen.

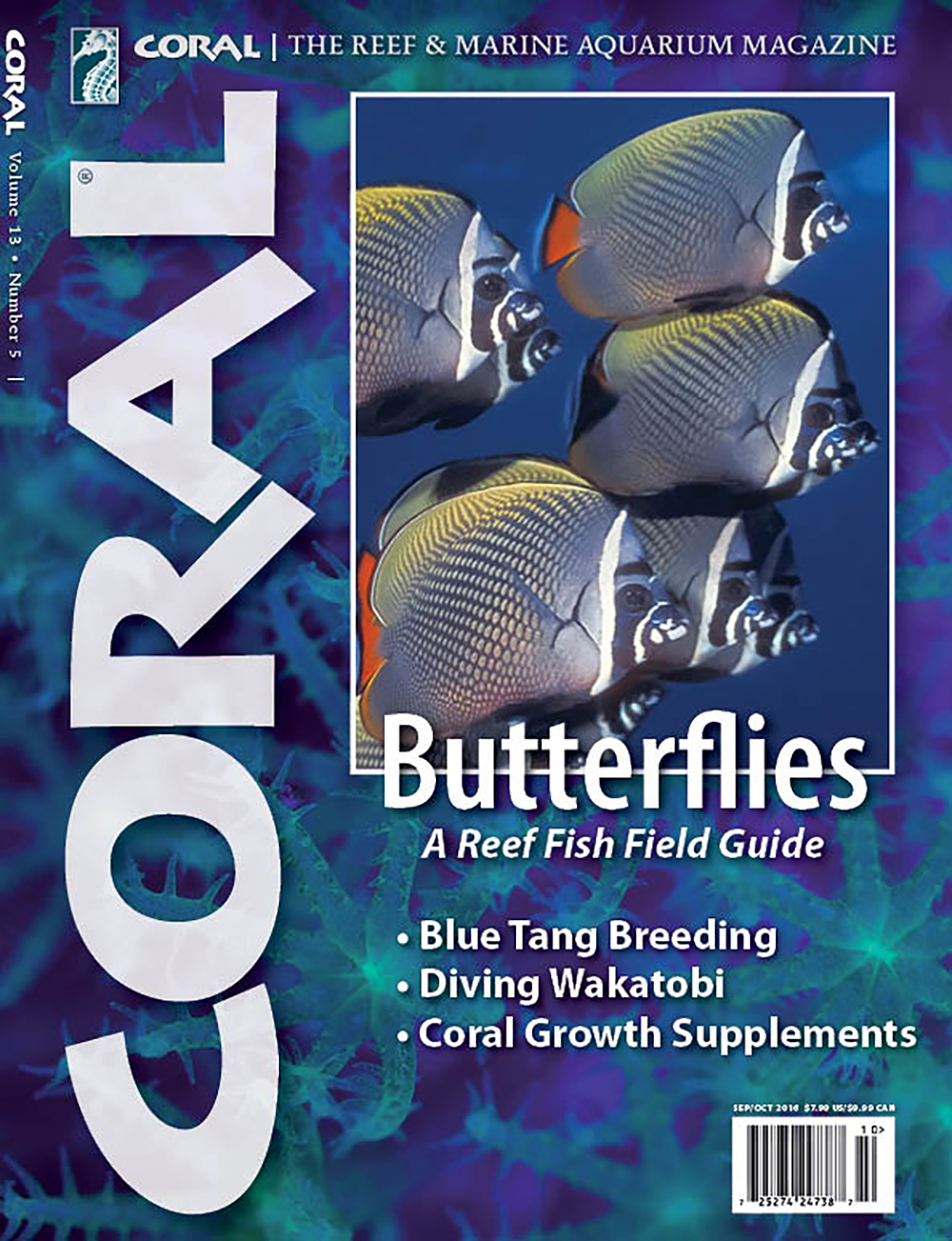

CORAL Advance Preview Cover, Sept/Oct 2016. Chaetodon collare shoal © Mark Strickland / SeaPics.com

Learn more about a convenient and personal subscription to CORAL, the world’s premier marine aquarium magazine.

I learned of the Banded Butterfly (C.striatus) aiptasia control from the aquarists at the Cleveland Metro parks Zoo. They were using them in their greehnouse aquarium. Aquarist Nick Zarlinga was who showed me the damage they can do to aiptasia.