A Dragon Wrasse, Novaculichthys taeniourus, is cleaned by Rainbow or Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasses, Labroides phthirophagus, on a reef in Hawaii. Creative Commons – CC-BY-SA 3.0 – cropped from original image by Brocken Inaglory

Capping off a week of claiming species firsts, starting with the successful breeding of Potter’s Angelfish and then the breeding of the Lemon Butterflyfish, Rising Tide Conservation is bringing it home with the last piece of the Hawaiian endemic trifecta. Avier J. Montalvo, working at the Oceanic Institute, has produced the world’s first captive-bred Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse, Labroides phthirophagus. I spoke with Montalvo last night, and he’s already done it again, producing a second group of four juveniles.

Throughout the day, Rising Tide has released the story of Montalvo’s success through social media channels. Here’s their story, told in the captions of each photo.

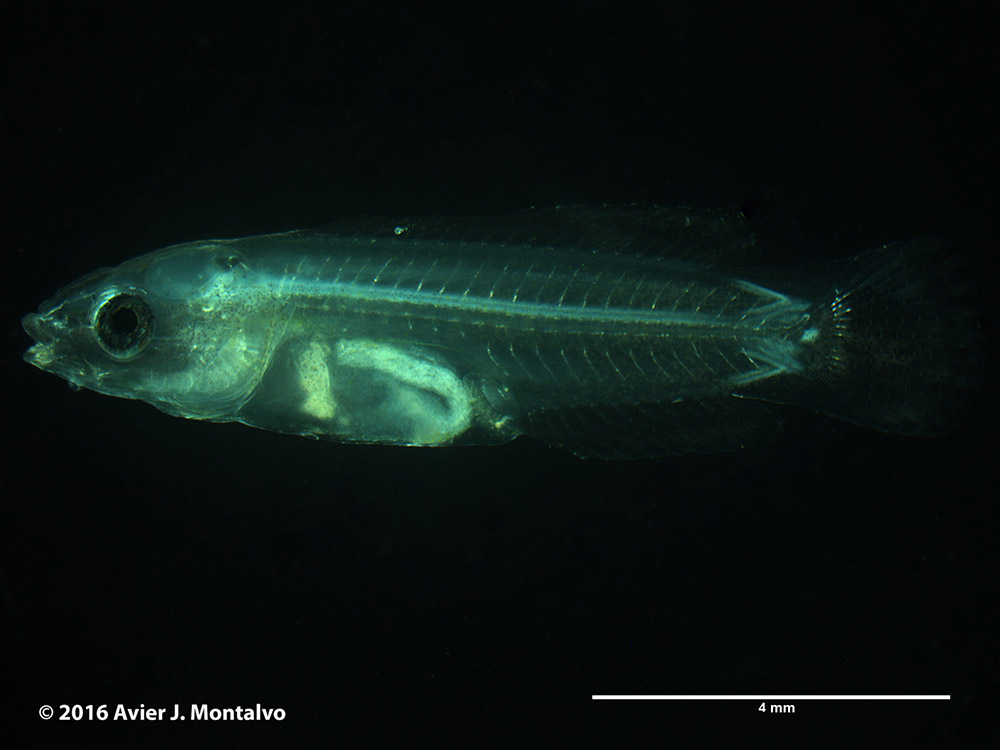

Egg collectors were deployed on the afternoon of 4/17/16 and collected on the morning of 4/21/16. There was a total of 32,900 eggs with 70% viability. This was the highest number of eggs collected to date. The eggs were stocked at a density of 23.03/mL in a 1,000L flow-through tank. The average rearing parameters for this collection were: 26.8 ± 1˚C and 30.0 ± 0.8 ppt. DO was maintained ≥ 6.0 mg/L, and pH ranged from 7.6 – 7.8. Most of the larvae I examined had well-formed eyes, mouths, and guts, with the yolks fully absorbed. The first feeding of copepod nauplii and background algae was provided. It looked like larvae were either Acanthurid (Tang) or Chaetodontid (butterfly). At approximately 30 dph, there was a different larva. A very different larva. Pictured here at 35 dph, at approximately 8.80 mm in length, was a long and slender larvae, spending most of its time around the walls of the tank, picking prey items off the side. The larvae had very well developed eyes, and a fully formed mouth and gut. It did not have a very deep body, but it did have well-formed fins, with blotchy speckles of pigment starting to develop.

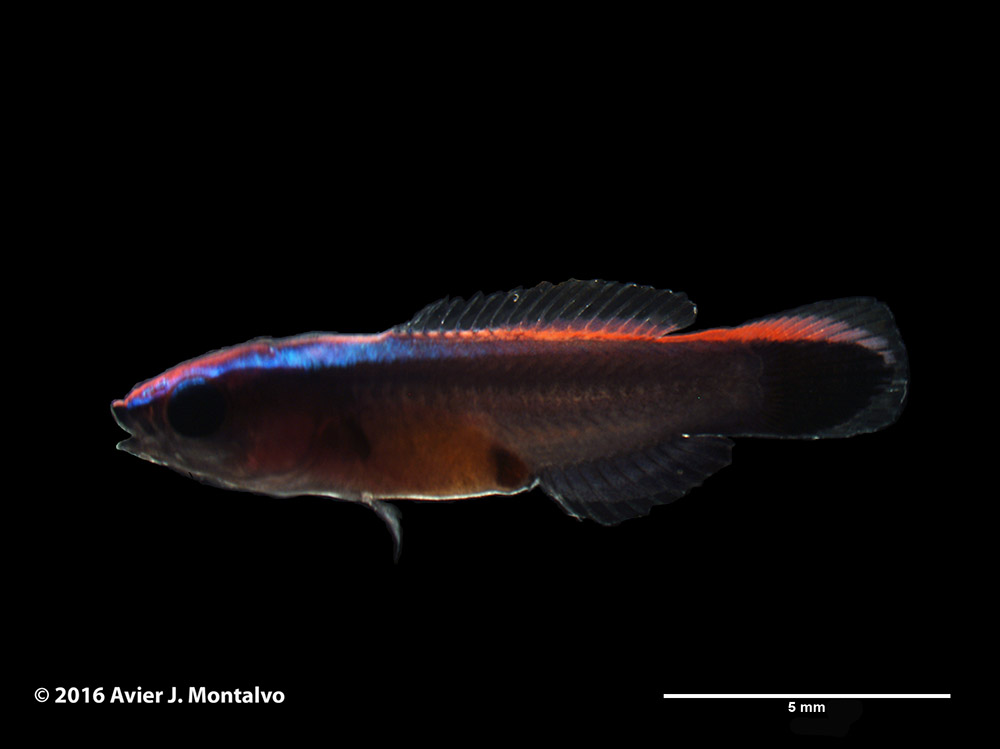

The larva was elusive but it showed up again while Avier was looking at the bottom of the tank a few days later. A brightly colored neon blue streak shot up towards the surface of the tank! He caught the specimen and examined it under the microscope. It was a completely metamorphosed fish. But which fish?? The little guy was moved into a 200L flow-through tank with settled fish from another collection. Pictured here at 41 dph, at a length of 13.88mm, the mystery fish had a neon, multicolored strip running from its head to tail, fully developed fins, and a round but slender, dark-colored body. It was a Labroides phthirophagus, the Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse! It was voraciously feeding on enriched artemia, frozen cyclopeeze, and flake. Interesting tidbit: this individual started exhibiting its cleaning behavior at 44dph (and the other fish in the tank did not like it!).

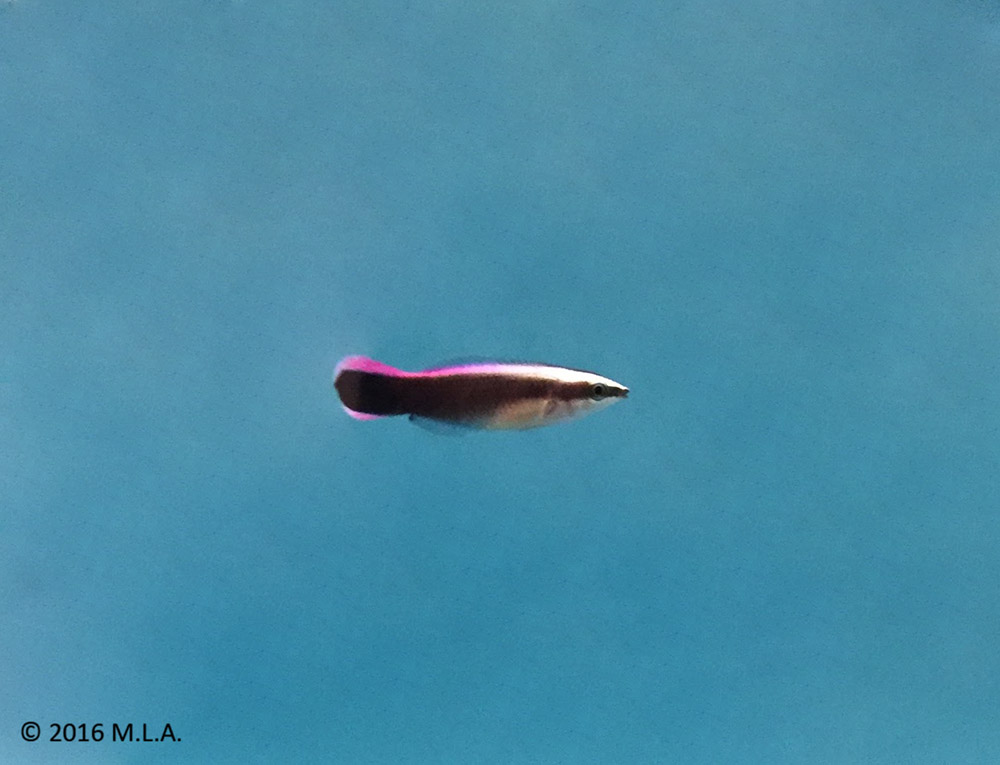

There is a single mated pair in the entire mixed-species tank, but that pair produced an egg that produced a larva that turned into this fish. This fish is the first of its kind to be reared in captivity, and it has significant implications for conservation efforts. Pictured here at 91 dph, the juvenile exhibited the narrow mouth, pointed head, and bright colors characteristic of this cleaner species. The multi-colored stripe had changed to resemble the distinctive purple coloration found on the adults, and the dark-colored body was now jet black.

At 118 dph, the growing juvenile has changed color again. Here’s what he looks like today. The IUCN reports: Labroides phthirophagus inhabits coral and rocky reef habitats, other than within the surge zone. This species is an obligate cleaner, feeding on the crustacean ectoparasites of other fishes, probably including gnathiid isopods, and also on fish mucus. While the population is not identified as endangered, the limited distribution of this fish makes them vulnerable to local environmental damage. As an aquarium fish, captive-reared specimens that eat like locusts show great promise for the hobby. Congratulations Avier on a job well done!!

Rearing By Accident

About three years ago, I reported on the world’s first captive-bred Cleaner Wrasse, Labroides dimidiatus. This occurred at Bali Aquarich under Wen-Ping Su, and it was quite literally a happy accident, as the eggs were collected alongside the target species (an Angelfish) and were simply reared by accident. Given the low cost of this species as a wild-sourced fish, it should be no surprise that Bali Aquarich didn’t pursue this success further, and to the best of my knowledge no captive-bred Cleaner Wrasses were ever made available to the aquarium trade.

In what is almost too coincidental to be ironic, it’s interesting to highlight that once again, this sibling species, the Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse, wasn’t exactly reared out of a targeted breeding effort. Rather, they’ve simply been one component of the cumulative nightly spawn collected out of a large display aquarium that houses many different families of pelagic spawning reef fishes. So it wouldn’t really be a stretch to suggest that, once again, another Cleaner Wrasse breeding first has happened almost by accident!

Redefining a Species Through Culture

For Montalvo, his roots as an aquarium hobbyist are revealed by what he finds most compelling about the work.

Avier J. Montalvo in a photo released Thursday, 8/25, along with the news that he had not reared just one Lemon Butterflyfish, but upwards of 100 at this point, some of which are visible in the net.

Montalvo found the rearing of the Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse noteworthy due to what he called a “short pelagic larval duration, very short in comparison [to the other fishes I’ve recently raised].” He continued, “[This is the] first wrasse I found [to settle] much earlier than the others.”

Generally speaking, marine fish breeders find fishes with shorter larval durations faster-growing and easier to rear; they simply spend less time in the more problematic pelagic phase of their lifecycle.

“Evidently, they don’t need to clean,” remarked Montalvo, addressing their reputation as obligate cleaners. “They don’t need to clean at this age, or at least up to this point in rearing. We know they’re not likely going to clean other larvae, but it’s unclear at what stage any nutrients provided by ‘cleaning/grazing’ would be ‘essential’ for optimum health. So, they may need to clean at some point…at least to live up to their name.”

When pressed to ask what these fish are feeding on, Montalvo didn’t hold back. For larval rearing, Montalvo knows they ate copepond nauplii and rotifers, because otherwise, “[the juvenile wrasses] wouldn’t exist.” Talking about the now-settled juveniles, Montalvo reports that, “The first individual started eating enriched artemia, Cyclop-Eeze, and flake. These next four I have on Cyclop-Eeze and Otohime. They have eaten pretty much everything.”

The diet of these young captive-bred wrasses is notable. According to Montalvo’s assessment, he fully believes that the Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasses would be “able to survive in captivity if they can actually be reared or trained to accept conventional aquaculture food items in addition to what nutrients they would receive from ‘cleaning.'”

Clearly, captive-breeding can redefine the aquarium husbandry of this species, as breeding has done for many other species in the past. Wild-collected seahorses are a great example, as they are reluctant to accept anything other than live feeds, while their captive-bred offspring can be gluttonous consumers of frozen shrimp! For a species that has “best left in the wild”-type recommendations surrounding it, the notion of a captive-bred Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse that eats anything you throw in the tank–with gusto, no less–represents a completely fundamental shift (I hate to invoke the overly-used phase “game-changing,” but that’s truly what this is).

Wild-caught Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasses will always be a challenge, but with dedicated breeding efforts, this beautiful species could become a highly accessible aquarium inhabitant for almost any aquarist. All it takes is the effort, and the market demand to support that effort.

A glorious Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse, here seen off Old Airport Beach, Maui, HI, at a depth of 10 feet. While still “best left in the ocean” as a wild-caught fish, captive-breeding could truly make this fish a welcome addition to our aquariums. By AM Smith – CC BY-SA 4.0

So, captive-bred, easy-to-feed Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasses everywhere in two weeks, right?

Not quite. “This is all baseline work…I think more work needs to be done for sure,” wrote Montalvo. Reflecting on the week’s news, “I want brood fish of all these species,” he mused, “to perfect and refine.”

This success means different things to different people. For Dr. Chad Callan, Director of the FinFish Program for the Oceanic institute of Hawaii Pacific University, it means further proof that the techniques his team developed to rear the world’s first captive-bred Yellow Tangs indeed work for other marine ornamental fish species. Dr. Judy St. Leger, President of Rising Tide Conservation and Vice President for Research and Science at SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment, sees the ability to propagate this species as an important conservation tool, given the restricted range of this Hawaiian endemic. For this author, it means a lot of the talking points surrounding both an impossible-to-keep species and the aquarium trade in Hawaii that supplies this species, are being redefined (see the op-ed, Hawaiian Cleaner Wrasse is Rising Tide’s Mic Drop).

Credits: From materials released by Rising Tide Conservation / Avier J. Montalvo

Trackbacks/Pingbacks