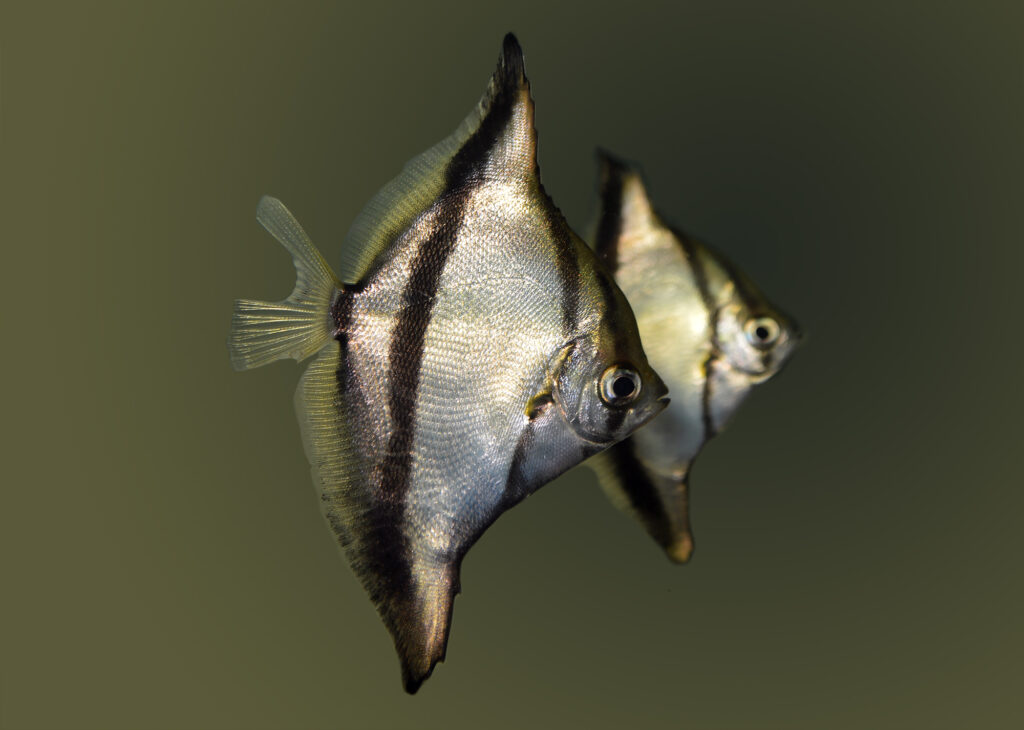

A pair of Florida-produced captive-bred Monodactylus sebae (aka. Mono Sebae or Sebae Monos), reared by Jonathan Foster of FishEye Aquaculture.

A dazzling species that defied easy culture

“We’re not sure if we’ve raised a million just yet, but we’ve definitely killed a million.”

– Jonathan Foster, FishEye Aquaculture

A Brackish Background

Before we delve into Mono Sebae, it’s worthwhile to take stock of the brackish aquarium hobby as a whole. It is an extremely underappreciated and overlooked niche within our passion, but it’s understandable how we got here.

The brackish water offerings at most aquarium shops, if they even bother to carry brackish fish at all, are often relegated to a single tank. It is easy to guess why; the choices are a bit limited. Thinking of brackish water fishes conjures only a handful of occasionally-available fish species including some of the various Puffers, Gobies, Scats and Monos. Maybe if you’re lucky Archers, Mudskippers, Four-Eyes (Anableps), Toadfish, “Freshwater” Frogfish, along with Green and Orange Chromides, get casually thrown into the “brackish” group and at times show up at your LFS.

Of course, there are some brackish species erroneously passed off by the aquarium trade as freshwater species, thus destined for improper husbandry at the hands of uninformed aquarists. As a prime example, the “Columbian Sharks”, a.k.a. “Silvertip Sharks” or “Blackfin Sharks” are neither freshwater fishes nor sharks; best known as Ariopsis seemanni, they’re a marine catfish species too often suggested as being freshwater, yet most decidedly are brackish fish that as adults are suggested to be best in full strength saltwater. Additionally, despite being well-suited to brackish environs, we don’t tend to think of the Mollies as “real” brackish fishes (and while they can be kept in purely freshwater, overwhelmingly they seem to do better with a little aquarium salt added, and most all can be brought to full strength saltwater). There are of course native brackish species such as the Sheepshead Minnow (Cyprinodon variegatus) and the lustworthy Diamond Killifish (Adinia xenica) to add to the diversity of brackish options, but when have you seen either of these at the LFS, or even through online specialty sources?

It doesn’t help that “brackish fish” often get lumped together by their singular (and perhaps over-generalized) shared preference for salinity levels far less than full-strength saltwater. The implication being that “oh, they’re brackish fish, just throw them all together.” Any hobbyist that does simply throw whatever brackish fish are available together (because they’re the only ones available) is probably going to deal with compatibility issues and quickly become discouraged. Obviously, not all brackish species are compatible, so even when we exhaust all possibilities to find candidate species, aquarists are still quite limited within the subset of species as they start choosing.

The requirement to add salt to the water for brackish fish certainly could be a stumbling block for less experienced & beginning aquarists (you may or may not remember the days when things like the nitrogen cycle seemed like daunting post-doctoral biochemistry, so cut the newbies some slack!). The limited options for livestock certainly add another reason for novice aquarists to skip the brackish water aquarium department. In fact, it very well could be that people get drawn into brackish water aquarium keeping primarily by the charismatic Pufferfishes and Archers more than any others. These oddball fishes have enough visual appeal and interesting behaviors going for them that people will seek them out.

As a result, brackish aquariums aren’t commonly the target of our collective aquarium keeping efforts. It’s therefore not surprising that brackish fishes aren’t generally the target of breeding efforts either.

When we also consider that many brackish fish have life cycles that emulate many marine fish species, and may require a range of salinity from spawning to hatch to grow out and maturity, it’s not surprising that the complexity would prevent a more straightforward approach that most freshwater fishes require. Thus, a freshwater aquarist trying to apply freshwater-honed techniques and ideas to many of the available brackish species is set up for failure from the get go. Indeed, when it comes to breeding many of the aforementioned species, it is the experienced marine aquaculturist who has more of the appropriate experience and resources at his or her disposal.

Enter Monodactylus sebae

Monodactylus sebae, often simply shorthanded Mono Sebae as a common name (and also known as the African Moony), is the less-commonly available of the two popular Mono species (if we can actually call any brackish-water fish “popular”). The related Monodactylus argenteus, the Silver Mono, is much more commonly seen, which makes sense given its wide Indo-Pacific range, whereas M. sebae is native to Africa’s west coast (the Atlantic side). Both are members of the family Monodactylidae, the Moonyfishes or Fingerfishes. The two other Monodactylus species seem completely absent in the aquarium trade, as are the two related Pomfreds / Pomfrets of the genus Schuettea. (That said, the Eastern or Ladder-finned Pomfred is quite the looker!)

Most aquarium references suggest that Monodactylus sebae is less hardy / more disease prone than M. argenteus, although the reasons for this reputation could stem from past histories of improper care, or the presumably less developed supply chain of aquarium fishes coming from West Africa. Combined with spotty availability and presumably stricter demands on care, it is not surprising that M. sebae is generally the more expensive of the two Mono species in the trade.

M. sebae reaches about 8″ in length at the most, but most people talk about this species in terms of height, rather than length. It is not unheard of to read about M. sebae reaching a foot (12″) or more in height. With these figures in mind, most recommendations for Mono aquariums are big; 125 gallons to 250 gallons or more. These recommendations stem not only from the size of the adults, but their very active nature.

M. sebae is a schooling fish; in my personal experience I’ve found them to also become very aggressive and belligerent in small groups (eg. 3 or less). So in reality, this is a schooling fish that I believe should be kept in larger groups of perhaps half a dozen or more (and thus in large tanks) as an adult.

Pursuit Of An Alternative

Jonathan Foster of FishEye Aquaculture is the breeder responsible for making captive-bred M. sebae to reality. Foster has worked in conjunction with Dustin Drawdy of Oak Ridge Fish Hatcheries to close the life cycle on this challenging species, which both businesses now offer to the aquarium trade. Saltwater-acclimated M. sebae are available from FishEye, while freshwater-acclimated specimens are available from Oak Ridge. Earlier this year I spoke with Foster to get the back story on this accomplishment.

FishEye Aquaculture had already seen success as a marine aquaculture facility working in conjunction with Rising Tide Conservation and TAL to rear numerous pelagic spawning marine fish species, most notably French Grunts (Haemulon flavolineatum) and Porkfish (Anisotremus virginicus), in commercial volumes.

Monodactylus argenteus has also been successfully spawned and reared in similar settings, where mass egg harvesting followed by blind rearing attempts would yield results. In my own recent memory, I recall the folks at the Long Island Aquarium cursing that they had reared M. argenteus yet again, when they had been hoping to rear things like Anthias and Angelfishes by harvesting eggs from the 20,000 gallon reef aquarium there. I’m not sure, but the preponderance of Mono eggs may have earned those fishes the boot from the reef tank so aquarists could focus on eggs from only other species.

As Foster explains it, pursuit of M. sebae as a Florida fish farm species started years ago when freshwater Angelfish, Pterophyllum scalare, were suffering massive losses from an iridovirus. Large scale farm customers were concerned about the loss of Angelfish as an offering, and a request went out for an alternative. M. sebae was identified as a candidate, presumably due to the general similarity in body shape and pattern when compared to a wild type Angelfish.

The Tropical Aquaculture Lab (TAL) at the University of Florida had been pursing the project of breeding M. sebae for some time. Foster reports that, “TAL had success and they documented it well for farms. However, no farms were able to duplicate it and the idea was shelved. We dusted off the idea 7 years later.”

Given these successes, it’s fair to say that Foster stood a good chance at being able to rear Monodactylus sebae at commerical scale.

Breeding Mondactylus sebae

Foster relays that it took several months of trial and error to successfully spawn and rear Mono Sebae. With hindsight, he now jokes “We’re not sure if we’ve raised a million just yet, but we’ve definitely killed a million.” While Foster won’t share his step-by-step protocol, he says that the key to success was to follow what nature does.

Foster noted that while M. sebae can be spawned and reared in a 100% marine environment over its entire life cycle, it performs better when being grown out during the juvenile phase as a freshwater fish. “We can raise them in saltwater environment, but moving them to the ponds at an early age was a huge advantage for yields, and this allowed for the fish to be available at a cheaper price than it has ever been offered before,” says Foster.

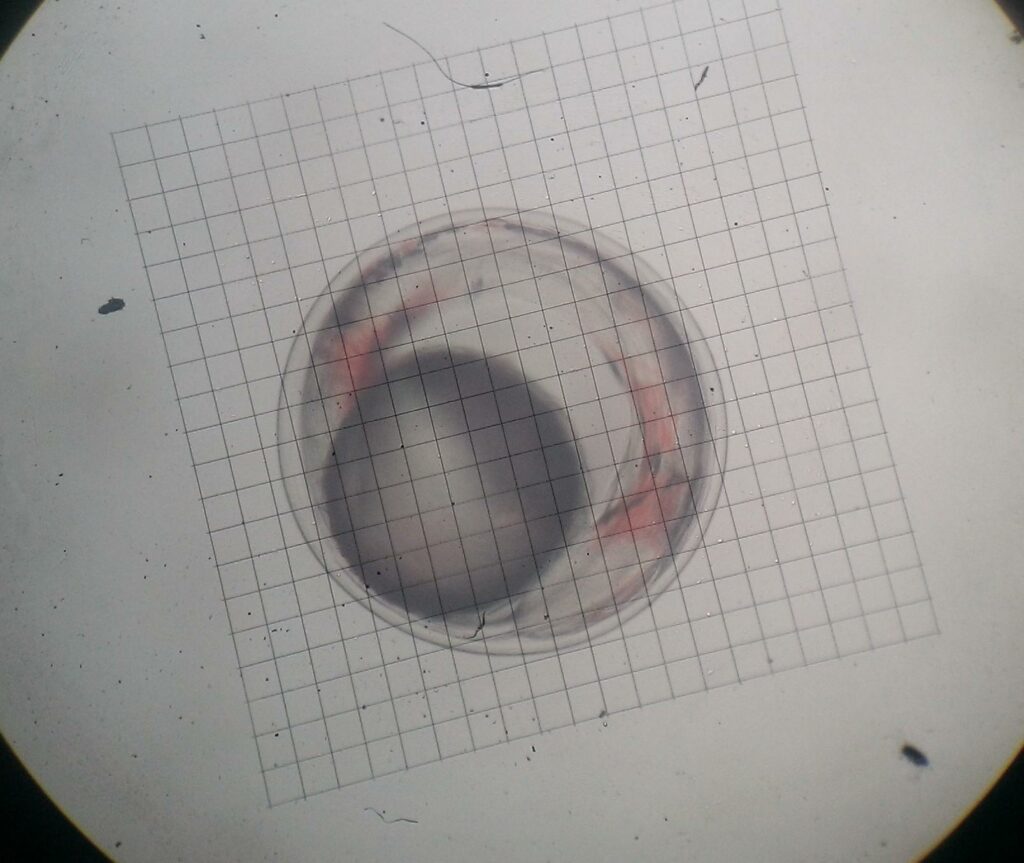

So Foster spawns the fish in a marine environment, producing small pelagic eggs which follow what I’ll call “traditional” marine larval development patterns.

The free floating eggs hatch as prolarvae (no eyes, no gut, no mouth, no gills), and spend time adrift as planktonic larvae.

Once the prolarvae have absorbed their yolk reserved and developed into functional larvae, they feed on zooplankton and grow in saltwater through settlement and metamorphosis, at which point a juvenile Mono Sebae is recognizably produced.

“Dustin [Drawdy] was critical for our success. Dustin’s knowledge with fragile freshwater fry is what helped,” shared Foster. It wound up being that the late larval / early juvenile phase was the biggest hurdle to overcome for the consistent rearing of this species.

So ultimately Mono Sebae spawned at FishEye go to Oak Ridge for grow out in a freshwater environment and eventual sale. Some return to FishEye, where they are returned to a marine environment prior to sale.

So what does Mono Sebae have going for it?

Simply put, Mono Sebae is one of those fish that people may have seen, but not really experienced. Dark, stressed-out single juveniles in a holding tank aren’t inviting; and I say this having seen them exactly in this fashion several times at multiple aquarium shops. M. sebae would be far more enticing if displayed and sold in groups of juveniles allowing them to be bold and active.

The past reputation for M. sebae being disease prone is certainly off putting, but that’s a thing of the past with captive-bred fish produced right here in the US. Foster is also quick to point out that disease should literally never be an issue with M. sebae. In reality, this fish can handle immediate and complete changes in salinity going from freshwater to saltwater, or the other way, without any acclimation. Parasites be damned…if your marine-acclimated Mono Sebae have something like Crytocaryon or Amyloodinium, throw them in freshwater and leave them there. Ich (Ichthyophthirius multifilis) on freshwater Monos? Throw them in saltwater; problem solved. I can personally verify that moving Mono Sebae from saltwater to nearly straight freshwater has certainly not killed, or even apparently stressed, the M. sebae in my care.

Mono Sebae can be mixed with several other brackish species; my top picks would be M. argenteus as well as the available Scatophagus varieties. The larger brackish gobies and/or Columbian Sharks will also do well, particularly if a large aquarium is furnished. Archers may make for good tankmates too, tending to stay at the surface while the Monos are a more midwater fish. Aquarium Design Group shows off an incredible example of a brackish community, including many of these fishes, on their website. This isn’t the only example put together by the Senske Brothers; all I’ll say is that well-aqauscaped boulders with Monos and Scats in a big tank is visually striking.

Of course, Mono Sebae is fully able to live in a marine aquarium; a shoal might make an interesting addition to appropriate tanks. It seems that captive-bred Monos also do well in straight freshwater, which would make M. sebae a great candidate as a larger schooling dither fish to utilize in aquariums that feature Cichlids or predators that require hard, alkaline water parameters. In truth, Mono Sebae might actually now be quite a versatile fish!

These days, with much effort, we now have a steady supply of captive-bred, Florida-bred Mono Sebae. Being captive-bred, they are not terribly shy, and settle in quickly to whatever suitable environment you wish to offer. When kept in groups, their activity level is notable and fills the need for a shoaling or schooling fish. These hardy, attractive fish are ready to make a statement, and are in fact ideal for most any aquarium salinity. Breeding has changed the story for this species, increasing availability and making the fish a better aquarium charge.

I’m pretty sure Bob Allen was the first to spawn these years ago.

I have indeed spawned (and raised a few) Monodactylus sebae, I wrote an article about it that appeared in Nov 2001 TFH. I tried them because I had heard about a fella in So. Cal named Wesley Wey, who was commercially producing M. sebae. He had written an article about it in article that appeared in a So. Cal publication in 1970!

Bob, as I cannot access TFH going back that far via digital, mind sharing some of what you shared back then here? No doubt things on a commercial scale are very different from how you may have reared a few M. sebae, and certainly the news here today is the commercial scale of what’s happening down in Florida.

What I knew from earlier reports of the breeding of M. sebae completely contradicts what we know about the breeding of pelagic-spawning marine fishes (which I would kind of consider M. sebae to be based, on the information shared with me) and also contradicts what I know of the breeding of M. argenteus and M. sebae today by fellow marine fish breeders. Those contradictions cause me to speculate that either there’s more than one way to breed M. sebae, that older literature holds even more secrets that we’ve failed to pick up on, or that some of the earliest claims may not have in fact been true.

This last statement may seem like a pretty strong allegation to make about something that occurred in 1970, but to have some perspective, even clownfishes hadn’t been successfully spawned and reared by that point in time! Furthermore consider the claims, for over a decade now, that the Pacific or Regal Blue Tang, Paracanthurus hepatus, was being bred in Asia. It started early on with tiny wild fish being harvested and sold as “Tank raised”…which literally was wild-collected post larval fishes being grown out in tanks (hence “tank-raised”) until hitting a marketable size. Most recently, there was the claim by researchers that they had succeeded…great…except the offered no proof; their documentation ended at 26 days post hatch. It wasn’t until this month that University of Florida’s Tropical Aquaculture Lab produced the undeniable proof that they had bred the species in captivity, and ironically, the methods claimed by earlier ‘successes’ failed to produce results.

I’d love to hear more on this topic if you’re willing to weigh in further Bob! Thanks for adding to the discussion.

Just a note to say how much a appreciate all of this info. I was wondering if I should be changing salinities during the life cycle of my fish. If I have Sebae Monos purchased in 2013 would they likely be tank bred and capable of fash acclimation from brackish to fresh water?

I do know from having kept Sebae Monos back in the 1980’s that that they seemed never to do well in strictly fresh water.

I have one individual five year old Mono exhibiting odd behavior now? t can swim normally and does when feeding. It however spends much of it’s time tilted slightly tail down and nose upward and wiggling quickly back and forth in one spot for lengthy periods of time. Any clues about this behavior?

Thanks for the great article on Monos. You also mentioned Archer Fish and Scats.

All three are native to Singapore, where I live. I have spent over 60 years observing them both in the wild and in the aquarium. In the wild, not all of their habitats overlap.

Archers are found in what we call the Back Mangroves. Salinity in these places is low. Sometimes, very rarely, Scats wander here too.

But I have never seen Mono argenteus here.

All three can be found in the Mangroves proper, which get inundated with sea water at high tide.

Out at sea, you will find Mono argenteus and Scats. Very, very rarely you will see an Archer, which probably got washed down and will head upriver soon.

These comments on where they live in the wild might help you decide what salinity level to have in the aquarium.

Truly amazing regardless of who bred these guys first. What needs to be done in the future is more wide spread publishing of these breeding methods in aquarium fish books instead of just publishing how to keep them alive in an aquarium.