Thriving corals being farmed by Bali Aquarium in Indonesia. Image: Vincent Chalias.

The live corals in a modern home reef aquarium would have been considered science fiction products just a few decades ago, as for years the world’s leading marine biologists believed that reefbuilding stony corals could never be kept alive in a captive system. Times have changed, and, as these short stories illustrate, continue to change in the culture and farming of once unkeepable Scleractinian corals.

CORAL Magazine’s 2014 article Bali High, by Vincent Chalias, presented a contemporary look at the history, challenges, and realities of coral mariculture in Indonesia. Combined with the full release of Wallacea Film’s 2013 documentary Hidden Gardens (watch below), it seems fitting to revisit these recent works to share an overview of how professional coral mariculture is undertaken to sustainably supply the aquarium trade with the corals that reefkeepers crave.

Bali High: Indonesia raises the stakes for coral culture

Article & images by Vincent Chalias

Partial excerpt from CORAL Magazine, September/October 2014

We started experimenting with farming stony corals some 15 years ago, and in 2000 we put our first racks into the sea in South Bali, Indonesia, directly offshore from Club Med and the exclusive five-star resort hotels of Nusa Dua. At the time, we had no idea how long our little adventure would last or where it might take us. Sink or swim, the world would watch us succeed or fail.

Six months later, our frags were growing fast and the venture was gaining momentum, but then, just as we were starting to feel elated about our experiment, we ran into our first bottleneck. We were obliged to abide by quotas that had been set for wild coral exports because coral farming wasn’t yet recognized by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species)—in fact, nobody even knew it could be done. We had wandered into a time warp where what we were doing was neither legal nor illegal and very hard to explain. There was no way to get the permits we needed for all the maricultured corals we were ready to ship.

At this point, some opportunists learned what we were doing and started their own coral “ranches,” collecting frags from wild colonies, mounting them, letting them grow for a few months, and then selling them as quickly as possible. As they were using wild coral quotas, they didn’t see the need to set up a proper broodstock farm, as we had done. Our method, at Bali Aquarium, which entailed finding the proper location, identifying the best species to culture, and experimenting with multiple management techniques, was expensive and time-consuming.

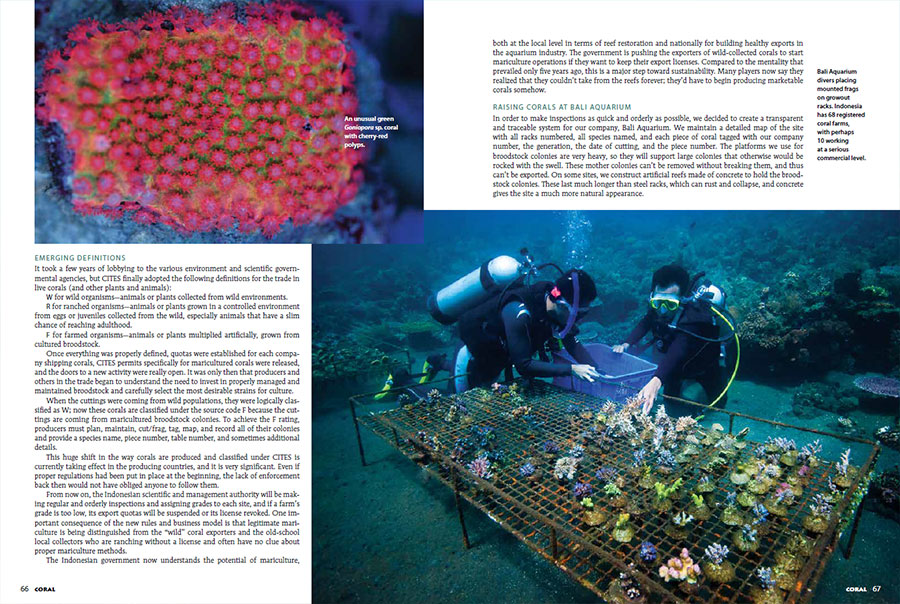

From the pages of CORAL Magazine: top left – An unusual green Goniopora sp. coral with cherry-red polyps. Main image – Bali Aquarium divers placing mounted frags on growout racks. Indonesia has 68 registered coral farms, with perhaps 10 working at a serious commercial level.

EMERGING DEFINITIONS

It took a few years of lobbying to the various environment and scientific governmental agencies, but CITES finally adopted the following definitions for the trade in live corals (and other plants and animals):

W for wild organisms—animals or plants collected from wild environments.

R for ranched organisms—animals or plants grown in a controlled environment from eggs or juveniles collected from the wild, especially animals that have a slim chance of reaching adulthood.

F for farmed organisms—animals or plants multiplied artificially, grown from cultured broodstock.

Once everything was properly defined, quotas were established for each company shipping corals, CITES permits specifically for maricultured corals were released, and the doors to a new activity were really open. It was only then that producers and others in the trade began to understand the need to invest in properly managed and maintained broodstock and carefully select the most desirable strains for culture.

When the cuttings were coming from wild populations, they were logically classified as W; now these corals are classified under the source code F because the cuttings are coming from maricultured broodstock colonies. To achieve the F rating, producers must plan, maintain, cut/frag, tag, map, and record all of their colonies and provide a species name, piece number, table number, and sometimes additional details.

This huge shift in the way corals are produced and classified under CITES is currently taking effect in the producing countries, and it is very significant. Even if proper regulations had been put in place at the beginning, the lack of enforcement back then would not have obliged anyone to follow them.

From now on, the Indonesian scientific and management authority will be making regular and orderly inspections and assigning grades to each site, and if a farm’s grade is too low, its export quotas will be suspended or its license revoked. One important consequence of the new rules and business model is that legitimate mariculture is being distinguished from the “wild” coral exporters and the old-school local collectors who are ranching without a license and often have no clue about proper mariculture methods.

The Indonesian government now understands the potential of mariculture, both at the local level in terms of reef restoration and nationally for building healthy exports in the aquarium industry. The government is pushing the exporters of wild-collected corals to start mariculture operations if they want to keep their export licenses. Compared to the mentality that prevailed only five years ago, this is a major step toward sustainability. Many players now say they realized that they couldn’t take from the reefs forever; they’d have to begin producing marketable corals somehow.

RAISING CORALS AT BALI AQUARIUM

In order to make inspections as quick and orderly as possible, we decided to create a transparent and traceable system for our company, Bali Aquarium. We maintain a detailed map of the site with all racks numbered, all species named, and each piece of coral tagged with our company number, the generation, the date of cutting, and the piece number. The platforms we use for broodstock colonies are very heavy, so they will support large colonies that otherwise would be rocked with the swell. These mother colonies can’t be removed without breaking them, and thus can’t be exported. On some sites, we construct artificial reefs made of concrete to hold the broodstock colonies. These last much longer than steel racks, which can rust and collapse, and concrete gives the site a much more natural appearance.

A percentage of our production is designated for reef restoration; we do this on our culture sites, as reef restoration only works if the whole ecosystem is restored and balanced. No coral will grow if the population of herbivores is not restored first and the sources of pollution are not eliminated. Unfortunately, these first steps are hard to implement.

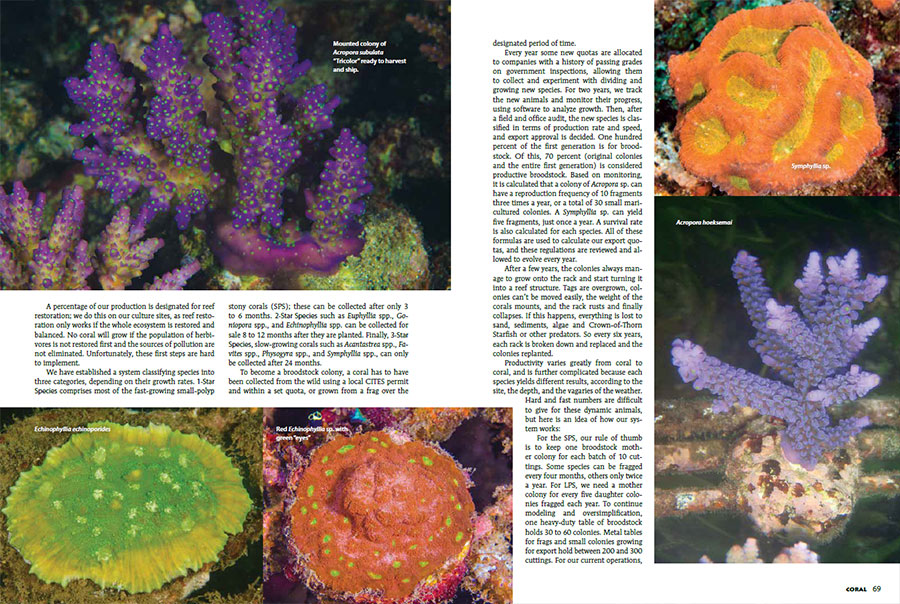

We have established a system classifying species into three categories, depending on their growth rates. 1-Star Species comprises most of the fast-growing small-polyp stony corals (SPS); these can be collected after only 3 to 6 months. 2-Star Species such as Euphyllia spp., Goniopora spp., and Echinophyllia spp. can be collected for sale 8 to 12 months after they are planted. Finally, 3-Star Species, slow-growing corals such as Acantastrea spp., Favites spp., Physogyra spp., and Symphyllia spp., can only be collected after 24 months.

From the pages of CORAL Magazine: Clockwise from top left – Mounted colony of Acropora subulata “Tricolor” ready to harvest and ship; Symphyllia sp.; Acropora hoeksemai; Red Echinophyllia sp. with green “eyes”; Echinophyllia echinoporides.

To become a broodstock colony, a coral has to have been collected from the wild using a local CITES permit and within a set quota, or grown from a frag over the designated period of time.

Every year some new quotas are allocated to companies with a history of passing grades on government inspections, allowing them to collect and experiment with dividing and growing new species. For two years, we track the new animals and monitor their progress, using software to analyze growth. Then, after a field and office audit, the new species is classified in terms of production rate and speed, and export approval is decided. One hundred percent of the first generation is for broodstock. Of this, 70 percent (original colonies and the entire first generation) is considered productive broodstock. Based on monitoring, it is calculated that a colony of Acropora sp. can have a reproduction frequency of 10 fragments three times a year, or a total of 30 small maricultured colonies. A Symphyllia sp. can yield five fragments, just once a year. A survival rate is also calculated for each species. All of these formulas are used to calculate our export quotas, and these regulations are reviewed and allowed to evolve every year.

After a few years, the colonies always manage to grow onto the rack and start turning it into a reef structure. Tags are overgrown, colonies can’t be moved easily, the weight of the corals mounts, and the rack rusts and finally collapses. If this happens, everything is lost to sand, sediments, algae and Crown-of-Thorn Starfish or other predators. So every six years, each rack is broken down and replaced and the colonies replanted.

Productivity varies greatly from coral to coral, and is further complicated because each species yields different results, according to the site, the depth, and the vagaries of the weather. Hard and fast numbers are difficult to give for these dynamic animals, but here is an idea of how our system works:

For the SPS, our rule of thumb is to keep one broodstock mother colony for each batch of 10 cuttings. Some species can be fragged every four months, others only twice a year. For LPS, we need a mother colony for every five daughter colonies fragged each year. To continue modeling and oversimplification, one heavy-duty table of broodstock holds 30 to 60 colonies. Metal tables for frags and small colonies growing for export hold between 200 and 300 cuttings. For our current operations, this is spread over more than a dozen sites, and the original small farm has grown considerably in size and complexity over the years.

GROWING DEMAND: A SURPRISE

The story continues, with Chalias describing the growing demand for maricultured corals, and the challenges Bali Aquarium’s coral farming operations face in meeting these demands. Chalias’ chilling remarks, “I do not wish to leave the impression that we think we can always deal with warming events.” Bali Aquarium’s maricultured corals are far from immune to the effects of climate change, with coral bleaching being a threat which Chalias and his teams must be ever-mindful of. To learn more about the future outlook for coral mariculture in Indonesia, and to read how Bali Aquarium is dealing with coral bleaching and warming oceans, subscribe to CORAL Magazine for access to the digital back-issue archive, or purchase a hard copy of the Sept/Oct. 2014 issue today.

Watch Wallacea Films’ 2013 documentary “Hidden Gardens – Coral farming in Indonesia”

This 11 minute documentary, created by Chris Paporakis, Alain Beaudouard and Rosanna Venturini, transports you to Bali Aquarium coral farms in south Bali. You’ll learn more about Chalias and his background and how he came to be culturing corals in Bali. Chalias himself explains why south Bali was chosen as an ideal location to mariculture coral. The documentary provides a general overview of coral biology and propagation methods, both land-based and underwater. You’ll get to see firsthand how corals are prepped and packed for export.