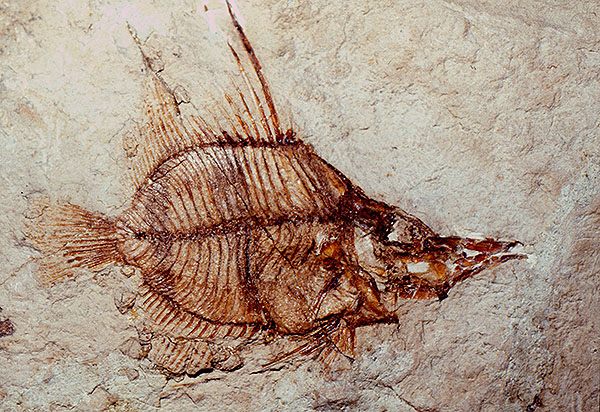

Fossilized Old Wife, Enoplosus pygopterus: common names reduce barriers to discussion and communication. Image: Cesiumfrog/Wikicommons

Essay by Jay Hemdal

Every species must have a singular name, or else humans would have no way to discuss them.

Languages and words evolve, with subtle changes occurring over time. Etymology is the study of how words are created and change, what their history is. In a broader sense, it is the study of a word’s “backstory.” The following are some mental meanderings about the names of aquarium animals, and how we use and misuse them.

Common names

A single species of fish may have a variety of common names. The common Bluegill also goes by the names Bream, Brim, Roach, Stumpknocker, and Copper Belly. However, it has only one scientific name: Lepomis macrochirus. Because of the confusion surrounding fish with multiple common names, the American Fisheries Society and the FishBase website have settled on a single common name in English for each species of fish. Some publishers capitalize common names, but many do not. (My publisher here believes that capitalized common names add clarity. An example of this thinking would be Yellow Tang, which always means Zebrasoma flavescens, while a tankful of small fish described as “yellow tangs” might be the juveniles of Acanthurus coeruleus, which happen to be yellow before turning blue.)

Do you call this fish a Bluegill or a Bream? Either way, it is a Lepomis macrochirus

Mistakes often happen with names: The Palette Surgeonfish, kept by marine aquarists, goes by a huge variety of common names in the English language alone. The most popular in the aquarium trade is “Hippo Tang,” which is derived from a mispronunciation of its species name, “hepatus,” that reminds people of the word “hippopotamus.” Enough people were confused that way, and the name stuck.

Other frequent misnomers with aquariums include “tubiflex” for “tubifex,” “chiclets” for “cichlids,” and “shrimp-brine” for “brine shrimp.”

Scientific names

Each species of fish is given a “Latinized binomial,” which is a fish’s scientific name, by taxonomists. This is usually written in two parts, Genus species. Written in italics, only the genus name is capitalized. For example, the Guppy is currently known as Poecilia reticulata.

A few organisms have a sub-species name, and this is written as a third word, after species. There can be only one valid scientific name for a fish at a given time, and no two fish can share the same valid scientific name. As scientific names change, the old ones are referred to as synonyms. Check Fishbase, and you will see that the Guppy has a handful of synonyms, all now obsolete:

- Acanthophacelus reticulatus

- Girardinus reticulatus

- Lebistes reticulatus

- Poecilioides reticulatus

- Girardinus guppii

- Acanthophacelus guppii

- Lebistes poecilioides

Remember that scientific names are the same no matter what language is being spoken, so they are the best way for people using different languages to be certain they are talking about the same species.

Some of my pet peeves with the use and misuse of names of organisms include:

People who point out that you are using old nomenclature: Scientific names do need to be changed at times, based on new genetic evidence or closer meristic study. At the very least, these changes help keep taxonomists gainfully employed. However, there are a few “armchair ichthyologists” out there who take great delight in correcting the scientific names used by others. They invariably do so in an off-putting manner, like in a public Facebook post, or in a room full of people. The reason for this is that Name Enforcers don’t want to correct you as much as to show themselves off in a better light. Privately correcting your misuse of a name serves them little purpose, so the more public the better. You can always counter this by saying, “…but you knew what species I was referring to, right?”

Those who correct your pronunciation of scientific names: Only the Church and a few scientists speak Latin now. As it is a dead language, native Latin speakers aren’t around to correct your pronunciation. When discussing the staghorn corals, they can be A-crop-ora or Acro-Pora—the same thing applies: ask the “language police” if they indeed know what species you are referring to—they always do!

One interesting side note is that the genus name of an African cichlid, Julidochromis or “Julies” as they are sometimes known, is always pronounced: “Jew-lid-o-chromis”. Latin doesn’t use the letter “J” and substitutes the letter “Y” – yet nobody calls this fish “You-lid-o-chromis”.

Identifying species based on a photograph: My ichthyology professor always taught us that “You cannot identify a fish based on a photograph,” and he was correct. Without the fish in hand for meristic measurements or genetic analysis, the best you can do is to say, “that looks like…” Still, aquarists online love to show off their aquarium knowledge by identifying random photographs posted by others. A related issue I have is with people who write about a species that they haven’t actually kept themselves! Using information gathered online or from books, they espouse husbandry information taken from others as their own. There ought to be a rule that a person cannot write about how to care for a fish they haven’t actually kept, or maybe not even seen alive!

Fun with phonemes

A striped octopus species was given the scientific name of Wunderpus photogenicus. This fanciful name was actually approved for use in naming this species by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.

Humorous scientific names for animal are not unknown, as science geeks often cannot resist having a bit of fun. Here are some other examples:

- Abra cadabra (Eames & Wilkins) 1957 (a clam)

- Aegrotocatellus Adrian and Edgecombe, 1995 (trilobite): Latin for “sick puppy.”

- Ba humbugi, a snail from Fiji.

- Bobkabata kabatabobbus Hogans & Benz, 1990 (parasitic copepod): Named after parasitologist Bob Kabata.

- Corydoras narcissus Nijssen & Isbrucker, 1980 (catfish): Named “narcissus” because the discoverers insisted that the describer name the fish after them.

- Galaxias gollumoides (fresh-water fish): Named after Gollum because it has large eyes and was found in a swamp.

- Ittibittium, a genus of mollusks that are smaller than those named Bittium.

- Mackenziurus johnnyi, M. joeyi, M. deedeei, M. ceejayi, Adrian and Edgecombe, 1997 (trilobites): As anyone who went to high school in the 1970’s can tell you, they are named after members of the punk rock group, the Ramones.

- Polypterus mokelembembe, Schafer and Schliewen, 2006: Named for the cryptozoological Congolese dinosaur-like creature Mokele-mbembe

- Ptomaspis, Dikenaspis, Ariaspis (Devonian armored jawless fish): Remove the suffix “-aspis” to see the joke.

I imagine that the sponge Spongiforma squarepantsii is a resident of “Bikini Bottom.”

We take this one for granted now, but really, calling a snail “Turbo” was obviously some taxonomist’s idea of a joke.

Actual common names of some Australian fishes:

Some are descriptive names: Painted Grinner, Bicolor Scalyfin, Many-rayed Threefin, Slimy Flathead, Old Wife, and Toothbrush Leatherjacket. (The Old Wife has also been called Bastard Dory, Double Scalare, Moonlighter, Zebrafish, and others.)

In other cases, the names are just plain strange: Humpty-dumpty, Pretty Polly, Blacktip Silverbiddy, Tasseled Wobbegong and Happy Moments.

And don’t forget about the Blackarse Cod, Snotgall, and Gobbleguts!

No doubt there are similar aspects of fish names common to other languages. In Indonesia, fish collectors simply refer to emperor angelfish at “Batman,” in reference to the cowl on the head of that species. Photoblepharon (Flashlight Fish) are sometimes referred to as “Le petit Peugeot” in French. This means “a small type of car,” and is a reference to the way that species’ photophores shine like tiny car headlights in the dark.

Don’t take the scientific and common names of your animals too seriously. Taxonomists are paid to worry about such things – you should strive to simply enjoy your aquariums! In the end, it doesn’t really matter that you can spell Phractocephalus hemioliopterus, or that Entacmaea rolls smoothly off your tongue – if you can’t keep them alive in your aquariums.