Healthy Hawaiian reef swarming with Convict Tangs. New program will provide rapid response to corals damaged by boats, anchors, storms and construction. Image; Daria White/Shutterstock.

Reef restoration biologists use accelerated growth techniques on stony corals

A modest collection of buildings at the Anuenue Fisheries Research Center on Oahu’s Sand Island in Hawaii has become home to the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) Coral Restoration Nursery. Part neonatal intensive care unit and part native coral bank, the new nursery will use professional-level coral husbandry techniques.

According to DAR coral biologist David Gulko, “Our technique makes use of non-coral reef source material (harbors, etc.) and provides protection from disease, water quality issues, aquatic invasive species, predation, and competition to create recombined coral colonies in a fraction of the time it would take to grow these corals naturally.

Department of Aquatic Resources biologist Dave Gulko: “Culturing corals in a fraction of the usual time needed.”

“Most coral nurseries around the world are in situ, meaning they are in the field. These types of nurseries excel at raising naturally fast-growing species of corals, which are not components of major reefs in the main Hawaiian Islands. At our Coral Restoration Nursery we’re focusing on ex situ, or a shore-based nursery, where we can grow large-size, adult colonies of coral for restoration purposes in a little more than one year.” Many of Hawaii’s slow-growing stony corals take a decade or more to reach sexual maturity in the wild.

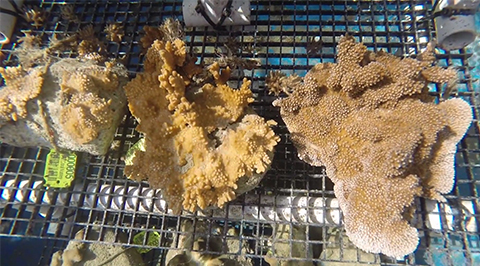

Small, started frags, left, are mounted in clusters and allowed to grow together, as shown at center. Speeded up growth gets the new colony to sexually maturing size, right, in about a year.

Aquatic mitigation bank

Most of the corals the nursery uses for transplantation will come from harbors, because they have lower ecological value than corals from natural areas and may be more resilient to disturbances and environmental changes. Using these corals also avoids damage to natural reefs and contributes to the upkeep and maintenance of manmade structures.

Rescued colony found in Kaneohe Bay in late 2015, identified as an unusual color morph of Tubastraea coccinea, Orange Cup Coral.

The Coral Restoration Nursery will also provide coral colonies for multiple restoration projects under the country’s first aquatic mitigation bank, which focuses primarily on near-shore coral reef resources. The Environmental Protection Agency defines an aquatic mitigation bank as “a wetland, stream, or other aquatic resource area that has been restored, established, enhanced, or (in certain circumstances) preserved for the purpose of providing compensation for unavoidable impacts to aquatic resources permitted under Section 404 or a similar state or local wetland regulation.”

According to Suzanne Case, chair of the Department of Land and Natural Resources, “The mitigation bank is akin to companies gaining carbon credits, in that costs recouped through the selling of coral restoration credits are based on lost ecological services from incidents like boat groundings and spills into the ocean.”

Accelerated growth technique

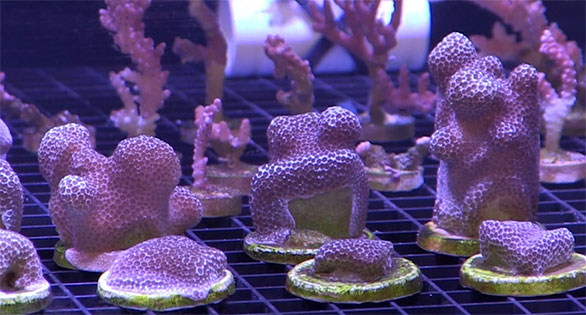

The DAR’s fast-growth protocol begins with the removal of a small coral from a structure, such as a harbor piling. The fragment is quarantined in the nursery before being separated into small pieces. These genetically identical fragments are exposed to optimal light, water, and nutrient conditions before being mounted in clusters that are allowed to spread and grow together. Once reaggregated into a colony at least 16 inches (40 cm) across, the corals achieve growth rates not seen in the wild.

Frags of stony corals collected in Hawaiian waters being growth in the new culture facilities. Hawaii is known for having slow growing corals, owing to its cooler water temperatures.

Early research has suggested that small frags of the same coral that grow together to form one larger colony reach a sexually mature size much faster than individual small frags left to grow as solitary corals. Prior to being transplanted back into the ocean, the new cultured colony is put in an acclimation tank that duplicates the conditions it will experience on the target restoration reef.

“Nearly one-quarter of the coral species found in Hawaii are unique to our islands and are also among the slowest-growing on the planet,” says DAR administrator Bruce Anderson. “We are hopeful [this technique] will help recover reefs that have been seriously degraded by human impacts like coastal development, vessel groundings, pollution events, and environmental factors such as climate change.”

Watch the Video Release from Hawaii DLNR:

References

From materials released by Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources (Hawaii DLNR), 2/11/2016Large, Native Corals Being Grown Using Fast-Growth Protocol

via (Hawaii DLNR)

###

I am a jeweler on Maui and Have had such a hard time making the coral pieces I collected before I became aware about coral. Now I have pieces and would like to donate profits from any pieces I make to research involving coral restoration. I would like to know more about what is happening on Maui and Hawaii in general for coral restoration. I hope there is a way I can contribute and also work together with a productive and effective organization.

I feel like coral jewelry should be illegal..

Has any findings on what the project has found for optimal growth been published? ie lighting and food types.

Yea yea

LETS GO

HUH