Several online references suggests that the Fireworm’s white bristles, aka chaetae, deliver a venom when stinging. But what’s the truth to that? Image by Silke Baron | CC – BY – 2.0

Are Any Bristleworms Actually Venomous?

That question first arose in modern times, I presume, when the first swimmer in warm tropical waters stepped on a fireworm and discovered just how much fun it was to hop around on one foot, cursing. By the time I got around to wondering about such things, I was a beginning scuba diver and graduate student all rolled up into a paranoid package. And we were told by both our profs, when we studied annelid worms, and our diving instructors, when they discussed hazards in the waters, that, “Hell, yes! They are poisonous!” That was about 40 years ago, in the early 1970s.

Howsoever, this era was also the beginning of marine product chemistry. In other words, big Pharma was starting to pour unending $$ in the investigation of anything, and everything, in marine systems that was rumored to have some sort of active chemical or chemicals. And, by golly, worms that could sting somebody were right at the top of the list. By the late 1970s, the jury came back in, and the verdict was that although the bristles of some worms, specifically the fireworms, in the Family Amphinomidae, could break off in your skin and cause some severe dermatitis, there was no detectable venom, probably because there was no venom to detect.

And so it goes. fire worms are so-called because they have defensive chaetae or bristles. These are different from most polychaete or Bristleworm bristles in that fire worms’ defensive bristles are secreted by a single follicular cell and are made of calcium carbonate. They are long, hollow, fragile, and sometimes even have serrated edges. When a predator, such as a fish, sizes up a worm for a meal, many fire worm species, such as Eurythoe complanata and Hermodice carunculata, can extend and erect their defensive bristles. This creates an unmistakable visual signal – a pair of parallel bright white lines running along each side of the worm. If the predator decides to ignore this bit of classical aposematic coloration and takes a mouthful of worm, they get a mouthful of broken slivers of material that is often barbed or serrated, and which can presumably hurt the fish like the proverbial dickens. This assessment is vouched for by many divers who show that they are not any brighter than the average fish and pick up or somehow force the worm’s bristles into their skin.

My female Premnas, who never learned. She would bite a Eurythoe about every 10 days. The bristles would eventually dissolve away. And she’d bite one again. I had her for about 8 years, and she did all 8 years.

One of my diving partners on my first tropical diving trip was a photographer. And, like most photographers, when she was in search of the perfect image, nothing else mattered. I was about 10 feet (3 m) from her and watching with fascination as she carefully set up for a shot and settled down gently on a small rock ridge bracing the bottom of the soft fleshy part of her arm on the top of a large Hermodice carunculata. She twitched when contact was most firmly made, but then, stalwart trooper (= brain-dead idiot) that she was, she carefully took her shot. Then she lifted her arm up to show what had happened. I was quite impressed. But not as impressed as she, as she had pressed the worm literally into the flabby part of her arm far enough that it was stuck there by its bristles. I was equally impressed by her language; she was cursing so loudly, I could hear her through her exhalation noise about 5m (16.5 feet) away.

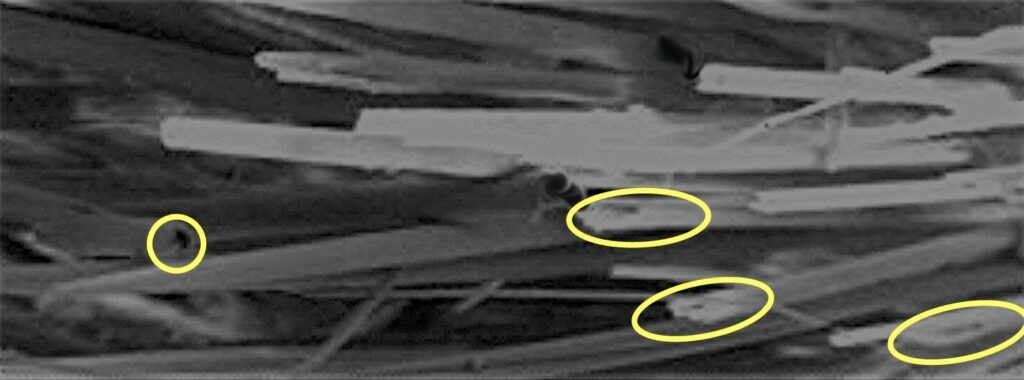

She came over to me and indicated that I should pull the worm out of its rapidly-reddening grove. However, on that dive I wasn’t wearing gloves, and I was going to be damned if I was going to pull the worm off her bare-handed. I was saved by the quick arrival of her husband, who was wearing gloves, and who gently removed the worm. I had with me an old 35-mm film canister to use as a small collecting jar, and we put the worm in the jar. Upon our return to shore, I wasted a bit of some 151-proof rum to preserve the worm, and upon returning home, I went to our lab’s scanning electron ,icroscope facility, dehydrated the worm, plated it in gold/palladium, and took the image you see here.

Broken bristles from Hermodice carunculata in an Scanning Electron Microscope, captured in 1982 by Dr. Ronald Shimek.

A few years after that, the dogma was pretty solidly set. The defensive bristles broke easily and irritated the skin, but there was no venom. And that is where situation stabilized. The idea that amphinomids or fireworms had venom in their bristles kept surfacing, but no definitive data ever supported that supposition. It became the wet equivalent of an old wives’ tale, an Old Scuba divers’ tale…and anybody in the know discounted it.

A few days ago I was asked to comment on the question of venom-laden chaetae yet one more time. I replied with this statement: “Now, I would love to see a reputable scientific journal article that describes the venom. If so, I will be thrilled to change my notes. But until then, they are defensive chaetae which are simply hollow calcareous tubes with serrated edges to gut the skin of a predator and irritate the Bejeezus out of it (and us), but they don’t (fortunately) envenomate us.”

After I made that reply, the powers that be decided this should be a blog entry, so I started to pull one together. It had been a while since I made the perfunctory check to verify that nobody had found some venom, and Mr. Google and I took a look.

And…

I will be dipped in …. something.

I found these articles which include data on fireworm venom:

Eurythoe complanata, taken off Cozumel, Mexico. The white defensive bristles are erected. The worm was about 20 cm (8 in) long.

As I said in the paragraph above, I am thrilled to find these data about the venom. I suspect now that some venom has been found, others will be found in some of the many other species of fire worms. Probably, there will be a different venom in each species, as that seems to be the way of venoms in closely-related species.

A small fire worm from cold water. It lives inside of sponges and is about 3 cm (2.2 inches) long. Virtually every bristle is a defensive bristle.

A close-up of a Eurythoe from my aquarium. The rounded, brownish structures are segmental gills. They are above golden, non-defensive chaetae made of chitin. Under those are the bright white and somewhat out-of-focus defensive chaetae.

About not finding the data on the venom until several years after the fact, well, search engines aren’t perfect, and these things happen. Other scientists missed it as well. There have been several articles dealing with fire worms taxonomically or ecologically in the past few years, and they have missed the boat as well (Barroso et al., 2010; Borda, et al. 2012; Bailey-Brock and Magalhães 2015). Even some discussions of venom in other annelids missed the amphinomid story (Halstead, 2013; von Reumont, et al. 2014).

The venom that was found was called Complanine, after an individual of Eurythoe complanata, and it apparently does cause severe irritation, although it is by no means fatal to humans. Interestingly enough, there are at least three cryptic species of E. complanata (Barrosa et al. 2010), and it will be interesting to see if they all have complanine as a venom, or even if all three have a venom.

Given the wide variety of fireworms found in our tanks (I have had at least six different species I could recognize in my tanks), I suspect there will be a large number of venoms eventually found in fire worms.

References Cited:

Bailey-Brock, J. H. and W. F. Magalhães 2015. Spawning event of Pherecardia striata followed by washed up individuals in Hawaii. Marine Biodiversity. DOI 10.1007/s12526-015-0335-7

Barroso, R., Klautau, M., Solé-Cava, A.M. and Paiva, P.C., 2010. Eurythoe complanata (Polychaeta: Amphinomidae), the ‘cosmopolitan’fireworm, consists of at least three cryptic species. Marine Biology, 157(1), pp.69-80.

Borda, E., Kudenov, J.D., Bienhold, C. and Rouse, G.W., 2012. Towards a revised Amphinomidae (Annelida, Amphinomida): description and affinities of a new genus and species from the Nile Deep‐sea Fan, Mediterranean Sea. Zoologica Scripta, 41(3), pp.307-325.

Halstead, B. W. 2013. Chapter 59. Segmented Worms. p.433. In: W. Bücherl and E. Buckley, Eds. Venomous Animals and Their Venoms: III. Venomous Invertebrates .Elsevier – Science – 562 pp. ISBN 1483262898, 9781483262895

Hi Ron — I’m pretty sure the “Chloeia cf pinnata” is mis-identified & that’s its really an euphrosinid. Cheers, Leslie

I have a picture I would like to send you to see if you can identify something I saw off the coast of Indian island in Puget Sound. How might I go about getting you the picture?

Tim Larson