An Anthiianae First: Captive-Bred Anthias at Long Island Aquarium

An excerpt from the March/April 2015 issue of CORAL Magazine

by Noel Heinsohn, images by Alex Pilnick

This story actually started on an October day last fall, when Joe Yaiullo and I set up an indoor plankton tow in the Long Island Aquarium’s 20,000-gallon (75,700-L) reef tank to collect pelagic eggs. Afterwards, as I went to unscrew the collection cup to see what had been collected from the captive system’s plankton, I found that it was full of hundreds of fertilized eggs from an unknown source. (The big display tank is swarming with an estimated 800 species of marine fishes, corals, and myriad invertebrates—and spawning events occur on a nightly basis.)

I separated the eggs into a rearing vat, where they were lightly tumbled for the next 24 hours. After the eggs had hatched, I turned down the water flow for the silvery, tiny prolarvae and used a pipette to select a few of them to examine under a microscope. Over the next few days, I repeatedly looked at a few larvae under a microscope as their eyespots became eyes, their mouths started to form, and their yolk sacs began to disappear. At four days post hatch (DPH), I began feeding them Parvocalanus crassirostris copepods, the smallest calanoid species offered by AlgaGen. This helped establish a copepod co-culture for when the larval fish would have consumed the last of their yolks—usually around 7 DPH.

Two weeks in and the larvae were big enough to eat rotifers. Since the copepods were still dense, I did not add many rotifers. Unfortunately, at 24 DPH, I lost most of the larvae for an unknown reason. From then until 30 DPH, the numbers dwindled down to the final two larvae. At 40 DPH, the larvae had reached the appropriate size to consume Artemia nauplii, and I began introducing the baby brine shrimp, but it took about a week before they showed any interest in the new food targets.

Coloration and settlement for the larger of the two started between 79 DPH and 81 DPH; I do not have an exact date, because I could not find the larva at this time. When next I saw it, it had already gained coloration and was settled on the bottom. At 81 DPH, it had taken on a bright orange coloration. The other larva, still much smaller, had yet to undergo metamorphosis and settlement.

At this point, I had made the decision (with advice from Todd Gardner, professor of marine biology at nearby Suffolk Community College) to move the fish to a smaller system. Even though this would be stressful for both the larvae and me, it would make for an easier way to control water quality. It would also be easier to try offering prepared diets to wean them off live foods. At 83 DPH, I moved them into a 20-gallon (76-L) tank that was connected to a larger system (around 150 gallons/568 L). After I had matched pH and temperature and drip-acclimated the fish for an hour, I moved them into their new home. The larger, settled fish easily adjusted to the new environment. However, the pre-settlement larva went to the bottom of the tank, lay on its side, and began to breathe heavily. After lying on the bottom of the dark tank for a few hours with some steady flow, the larva perked back up and started swimming back at the surface.

Unraveling the mysterious identification of these fish started when Professor Gardner first suggested they were Anthias. I knew that they could only have been from one of the many pelagic species that spawn in the tank. A lot of the initial larval stages I observed appeared very similar to Frank Baensch’s documentation of Pseudanthias bicolor and Odontanthias fuscipinnis, two species Baensch captive-reared from wild-collected eggs. Once the larva had settled and gained its orange coloration, it was obvious to us that it was an Anthias.

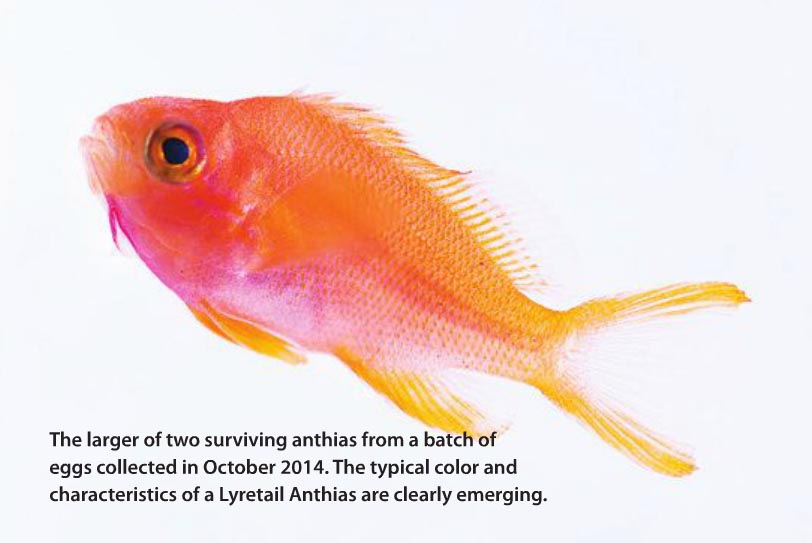

Up until a few days before writing this report, I wasn’t sure which species of Anthias I had reared. Knowing that the Long Island Aquarium’s large reef display contains seven different species of Anthias, all of which spawn regularly, there were several options. The orange coloration of this fish helped to narrow it down. The dead giveaway was when Alex Pilnick (of ReefGen) and I started taking some new photos of the Anthias for this article. As we looked through the photos, there it was: a purple striping from its eye down and a purple arc above its pupil. The species that had been brewing for the last few months was Pseudanthias squamipinnis, the Lyretail Anthias!

The larger of two surviving anthias from a batch of eggs collected in October 2014. The typical color and characteristics of a Lyretail Anthias are clearly emerging.

We also photographed the smaller post-larval fish, which has yet to be identified. It is the same age as the Lyretail, but it is just starting to gain pigmentation. It’s about half the size of the Lyretail and a bit stubby. It may just be a runt that is developing at a slower rate, or it could be a different species. Only time will tell.

Post-settlement smaller larva starting metamorphosis at about 80 days post-hatch. Its species ID is still not confirmed.

Several people deserve credit for helping make this happen. My gratitude goes to Joe Yaiullo, curator and co-founder of the Long Island Aquarium (formerly Atlantis Marine World), for providing the best Anthias broodstock around; aquaculturist Todd Gardner for keeping an eye on things and sharing his vast knowledge; the best crew of aquarists for being there to cover for me on the days I was not there; Alex Pilnick for taking some amazing photos; and, lastly, AlgaGen for supplying the live copepods we used to rear the Anthias. It took quite an array of talent and support to bring that first little fish to this point, but it does represent the first captive-spawned and -reared specimen in the subfamily Anthiianae to be reported.

Editor: An upcoming issue of CORAL Magazine will feature Noel Heinsohn’s follow-up report, which will give rearing details and hopefully reveal the identity of the second post-larval fish.

Like what you’ve read? CORAL Magazine is committed to bringing you important news on the latest aquaculture breakthroughs. Ensure you never miss a story like this – Subscribe to CORAL Magazine today!