Snorkeling in Kona, Steve Jurvetson captured a swarm of reef herbivores so thick that you can barely see the substrate. While the Yellow Tangs and Convict Tangs are very obvious, look closely. You’ll see Unicorn Tangs, Achilles Tangs, White Cheek Tangs, Orange Shoulder Tangs, and buried in the chaos, a Guttatus Mustard Tang, the Hawaiian Humbug Damselfish, a Moorish Idol, a possible Brown Surgeonfish, and probably even more. Image by Steve Jurvetson | CC-BY-2.0

Hawaiian legislature to consider 7 bills to change aquarium fishery—including 3 seeking an outright ban on marine livestock collection

By Ret Talbot

For decades now, the harvest of Hawaiian reef fishes for the global aquarium trade has fueled a heated, emotional debate, with aquarium fishers and those who work in the trade on one side and anti-aquarium fishery activists on the other.

Despite an effective, multi-stakeholder approach to fisheries management in Hawaii—despite data that consistently show sustainability—these activists unfailingly succeed in having bills introduced to the Hawaii State Legislature each year that would close the aquarium fishery. This year is no different with seven aquarium fishery-related bills before the Legislature.

Hawaii: A Source of Premium Fishes

The loss of the marine aquarium fishery in Hawaii would be a blow to the aquarium trade and hobby in the U.S. and abroad. The aquarium fishes harvested in Hawaii reach the mainland by one of the shortest supply chains available to North American aquarists. As a result, Hawaiian fishes are consistently healthy with extremely low mortalities. Because Hawaiian fishes are harvested in a well-managed fishery with copious data supporting fishery sustainability, they represent one of the best choices for environmentally aware aquarium keepers.

While health and sustainability are paramount for some aquarists, others note that losing Hawaii would mean that several Hawaiian endemic species would likely disappear from the hobby. Examples include several dwarf angelfishes, a number of butterflyfishes, and an array of popular wrasse species.

Not everyone agrees the aquarium fishery in Hawaii is well managed and sustainable. In fact, some of its most influential critics argue it’s not even a fishery at all. Individuals like Maui-based Robert Wintner (aka “Snorkel Bob”) believe the aquarium trade is unethical and that no reef fishes should be harvested for aquaria. He contends that aquarium fishermen are responsible for “devastating” changes on beautiful Hawaiian reef areas.

Other anti-aquarium activist like Rene Umberger, also from Maui, are open to the idea of an aquarium hobby based solely on aquacultured fishes. Either way, both Umberger and Wintner, and the activist groups they represent, have demonstrated a dogged commitment to closing the State’s most valuable inshore fishery through legislation.

Science Sides with AQ Fishery

The repeated attacks on the aquarium (or so-called “AQ”) fishery fly in the face of the data and are no doubt frustrating to fishers and aquarium fishery advocates. It’s important to remember, however, that the system has time and again proven it works. Each year anti-aquarium fishery bills come up, and each year they fail to become law. In many cases they fail to even be heard or make it out of committee. In large part this is because individuals take the time to make sure the science and the data are seen and heard.

Local stakeholders and scientists annually go to the Legislature and present oral comment. Others take the time to submit electronic testimony. Groups like the Pet Industry Joint Advisory Council (PIJAC) in Washington bring their resources to bear on proposed legislation that threatens to limit or close the fishery. Because of all these efforts, the data usually prevail, but that will only remain the case if individuals are informed.

So how do this year’s seven aquarium-fishery related bills stack up against the data? Have Hawaii’s reefs been devastated by the aquarium fishery as some critics contend? Are fish populations being wiped out by over-collection? Are animals harvested for the aquarium trade subjected to cruel treatment? Or, as others argue—does Hawaii stand as an example of one of the best-studied, best-managed aquarium fisheries anywhere in the world?

To answer these questions, we turn to the fisheries managers on the ground and, of course, to the data.

The Ban Bills

This year there are three bills that would end aquarium fishing in Hawaii outright. They are Senate Bill 322 (SB 322) and House Bills 606 (HB 606) and 873 (HB 873), and they may collectively be called the “ban bills.”

Of the three ban bills that could put an end to the aquarium trade in Hawaii, HB 873 is perhaps the must illustrative, and it’s the one on which this article will focus. While the other ban bills generally lack context, simply criminalizing or calling for the prohibition of the sale of aquatic life for aquarium purposes, HB 873 outlines the rationale behind the Bill in a six-paragraph preamble. This preamble lays out a series of largely familiar arguments supported by mostly unsourced data, and, in the absence of additional information, it serves as justification for all of the ban bills. [PDF: Download the original House Bill 873]

Overall, HB 837 claims the aquarium fishery “threatens Hawaii’s reef environments and the socioeconomic benefits they provide.” It alleges the aquarium industry “has operated for over fifty years with no limits on the volume of take and no limits on the number of permits.” As a result, the Bill claims that “[s]pecies targeted by the industry are three to ten times more abundant in areas protected from aquarium-collecting than in areas where the industry operates.” It further claims that the aquarium fishery has devastated stocks of iconic yellow tang (Zebrasoma flavescens), claiming their population is “depleted in many areas, decreasing by seventy to ninety per cent [sic].”

How accurate is this dismal picture of the aquarium fishery? While there are shreds of truth in HB 873’s preamble, to fisheries managers and other stakeholders who have worked for over a decade to create a well-managed, sustainable fishery supported by data, the Bill is a slap in the face. State legislators who mandated the multi-stakeholder approach with Act 306 back in 1998 are likely equally offended.

State marine biologist Dr. Bill Walsh is a long-time proponent of science-based aquarium fishery rules. Image: Ret Talbot.

Surprise Allegation: “Over-harvesting of Coral”

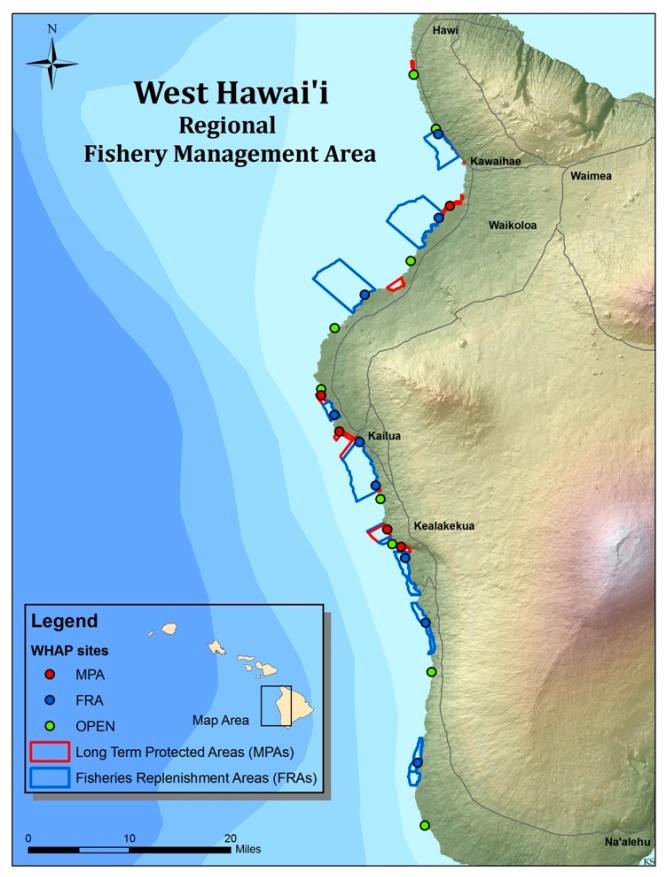

So how does the State’s aquarium fishery stack up to the allegations? Dr. William Walsh, an aquatic biologist with the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources’ (DLNR) Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR), says there are literally “millions more fish on the reefs,” and he says he has the data to prove it. A five-year report on the West Hawaii Regional Fishery Management Area (WHRFMA), the State’s largest aquarium fishery, finds that management has been increasingly successful. Specifically, Walsh points to the creation of Fish Replenishment Areas (FRAs) and Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which he says have played a significant role in population increases.

While much of the debate is focused on whether or not the harvest of herbivorous fishes such as the Yellow Tang is sustainable, the preamble to HB 873 begins with a surprising statement:

“The United States Coral Reef Task Force has reported that severe over-harvesting of coral by the aquarium industry occurs in Hawaii.”

For fisheries managers like Walsh, as well as for anyone with even the most basic awareness of the fishery, this opening statement, while perhaps effectively appealing to the emotions of the uninformed, clearly represents the misinformation and misrepresentation of the science so frequently employed by anti-trade activists in Hawaii.

With the recent listing of 20 species of coral under the Endangered Species Act and the ongoing, well-publicized dialog in the media about the plight of coral reefs, it’s perhaps not surprising that an anti-aquarium fishery bill would lead off with allegations of “over-harvesting of coral” for aquaria.

The trouble is, however, coral is not harvested for the aquarium trade in Hawaii.

False “Facts” Underpinning HB 873

While a representative speaking on behalf of the Coral Reef Task Force was unavailable for comment, Emma Anders of DAR and who sits on the Coral Reef Task Force, points out that the harvest of coral and live rock is prohibited in the Hawaii administrative rules. “I would be very surprised that the Task Force would report severe over-harvesting of coral in Hawaii and have not heard anything like that in the two years I have sat on that task force,” she says.

Dr. Walsh says there is no evidence of illegal coral harvesting in Hawaii. “To the best of our knowledge there is no harvesting of coral by the [aquarium] industry in Hawaii, as all stony corals, pink, gold and black corals and live rock are protected—no taking and no sale of same.” “They’ve been protected for quite a long time.”

In light of this, some observers suggest that the fact that the authors of HB 873 chose to lead with such an egregious falsehood perhaps calls other of their claims into question.

Mix of Fact and Fiction

When it comes to the other allegations in HB 873’s preamble, there is a mix of fact and fiction that ultimately draws a conclusion—the aquarium fishery must be closed. This position, however, is inconsistent with the State’s own historical data.

A point-by-point analysis of the Bill and the data suggest that while the threats to Hawaii’s reefs are real and need more attention in the form of effective management, the aquarium trade should not be the sole (or even the primary) focus of those acting on behalf of the State’s reefs.

For starters, the Bill states, “Hawaii’s reefs are the world’s third-largest source of wildlife for aquarium hobbyists.” This may sound problematic given the size of Hawaii compared to the size of Indonesia and the Philippines, the two largest source countries for the U.S. aquarium trade. Looking at the actual data, however, tells a different, less dramatic story.

While Hawaii is important to the U.S. trade in marine aquarium animals, the data show it is nowhere near the scale of Indonesia or the Philippines. In 2005, nearly 5.8 million fishes were imported into the U.S. from the Philippines and almost 3.3 million from Indonesia. That same year, 510,112 aquarium fishes were caught and sold Hawaii, making it the third largest aquarium fishery, but representing well below 5% of the total world catch. (Source: DLNR and independently verified via Rhyne et. al.)

“Threat to Tourism”

HB 873 continues, claiming the catch of half a million or so fishes that are harvested in the Hawaii aquarium fishery each year “threatens Hawaii’s reef environments and the socioeconomic benefits they provide, including to tourism—a crucial contributor to the State’s economy, and as sustenance for local families.” While it’s true that any extractive industry poses a threat to the resource, fisheries managers in Hawaii point out that aquarium fishing is far from the only fishery activity.

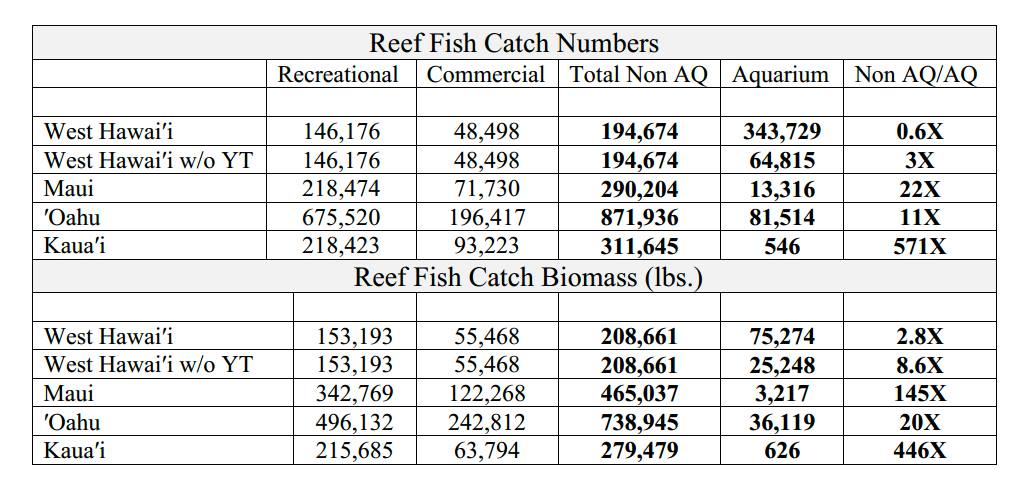

“Other types of fishing, both commercial and non-commercial target reef fishes,” says Dr. Walsh, referring to the State’s food and sport fisheries. “Almost everywhere in Hawaii the catch in terms of reef fish numbers, and especially biomass, substantially exceeds the take by aquarium collectors.” [See Table 1]

Table 1. Island comparison of the number and pounds of reef fishes caught by recreational and commercial fishers relative to aquarium collectors 2008-2011. The far right column represents Total Non AQ catch of reef fish relative to the catch taken by aquarium collectors. Credit: Walsh (2014)

In West Hawaii, where the vast majority of aquarium fishing takes place, the total aquarium reef fish catch does exceed total non-aquarium reef fish catch in terms of numbers, but the reef fish catch biomass for the aquarium fishery is well below half of the total non-aquarium reef fish catch.

In fact, the total aquarium fish catch biomass in West Hawaii is less than half that of the recreational fishery, which is almost entirely unregulated (Hawaii does not require saltwater anglers to purchase a fishing license). On other islands, the non-aquarium catch in terms of numbers of reef fishes harvested is as much as 571 times the aquarium catch.

While it’s critical to effectively manage each fishery (including the aquarium fishery), to claim, as HB 873 does, that the “loss of wildlife” as a result of the aquarium fishery “threatens Hawaii’s reef environments and the socioeconomic benefits they provide” is a red herring that ignores the more significant problem.

Effective Regulation?

HB 873 claims “[t]he aquarium industry has operated for over fifty years with no limits on the volume of take and no limits on the number of permits.” In reality, DLNR points out that all existing size and bag limits for reef fishes apply equally to all fishers including aquarium fishers. “This has been the case for many years,” says Dr. Walsh. “In recent years aquarium take has also been markedly restricted in West Hawaii to just 40 fish species.” He also adds that size and/or bag limits now also exist for the three most heavily collected species.

In terms of the number of permits, it is true that there is currently no limit on the number of aquarium fishery permits issued. This is, however, the case for all fishing related permits, licenses and registrations at present in Hawaii. Nonetheless, fisheries managers, as well as some stakeholders, believe limiting the number of permits is probably a good idea.

“The West Hawaii Fishery Council, A DLNR community advisory group,” Dr. Walsh says, “has been working on establishing a limited entry program for aquarium collecting in West Hawaii.” To date, both legislative and administrative rulemaking efforts to establish a limited entry fishery have failed.

Abundance

When it comes to the Bill’s claims regarding abundance, fisheries managers say there is no published data of which they are aware that supports the numbers cited in the Bill. HB 873 says species “targeted by the industry are three to ten times more abundant in areas protected from aquarium-collecting than in areas where the industry operates.”

The best data on the State’s aquarium fishery exists in West Hawaii, which accounts for nearly 70% of the State’s overall aquarium catch (67% of value). Those data regarding the 40 species legally harvested in the West Hawaii fishery show the following:

• Six species are consistently more abundant in areas protected from aquarium collecting (FRAs and MPAs) than in areas open to collecting.

• Seventeen species are more abundant in open areas than in the protected areas.

• For 11 species there is no consistent pattern over the past 15 years.

• The percentage difference between areas closed to aquarium fishing and open areas ranges from 4% (multiband butterflyfish, Chaetodon multicinctus) to 77% (bird wrasse, Gomphosus varius).

“These differences,” says Dr. Walsh, “are nowhere of the same magnitude [claimed in HB 873].”

The Iconic Yellow Tang

HB 873 also alleges that “[r]egulations have thus far failed to maintain populations of crucial species at levels necessary to protect Hawaii’s coral reefs.” The argument here is that the most popular aquarium species are herbivorous species like Yellow Tang, and these species have experienced the greatest declines in population. “As the most heavily targeted species,” HB 873 claims, “the population of yellow tang has now been depleted in many areas, decreasing by seventy to ninety per cent [sic].”

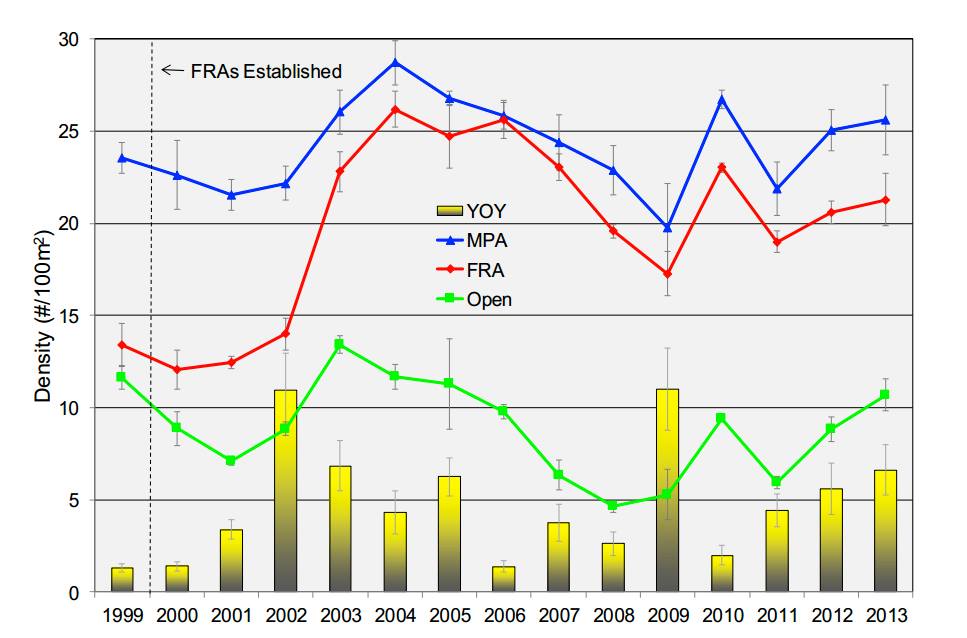

The data show that, over the past 15 years, the population of Yellow Tang has increased 64.5% in FRAs, which are closed to the aquarium fishery. Over that same time, the data also show the abundance of Yellow Tang in open areas has not significantly declined. “Based on intensive monitoring in West Hawaii,” says Dr. Walsh, “we know that the no-aquarium collecting Fish Replenishment Areas, implemented in 1999, have been very successful in increasing populations of yellow tang.”

“Overall changes in yellow tang abundance (Mean ± SE) in FRAs, MPAs and Open areas, 1999-2013. Yellow vertical bars indicate mean density (May -Nov) of Yellow Tang Young-of-Year (YOY). YOY are not included in trend line data”. Source: Walsh (2014)

Overall, Yellow Tang abundance in the 30’-60’ depth range over the entire West Hawaii coast has increased by over 1.3 million fish (up 58%) from 1999 to 2013. The current population across all areas is estimated to be 3.6 million fish. According to fisheries managers, there are also no significant differences in the abundance of adult Yellow Tang in open versus closed areas in shallow water.

The Importance of Herbivores

Continuing with the focus on herbivorous fishes, the Bill claims a “decline in herbivorous fish are a known stressor to coral reefs” and “research shows that two-thirds of Hawaii reefs are now dominated by the type of algae upon which herbivorous fish would typically feed.” The data, however, again tell a different story. In West Hawaii, for example, macroalgae cover in 2011 at 25 monitored sites ranged from 0% to 6.3%. Twenty-two of the 25 sites surveyed had less than 1% macroalgae cover, and this is in the same region where the majority of aquarium fishes are collected.

While there is a lot of misinformation when it comes to the specifics, HB 873 makes some really good points about the importance of herbivorous fishes in general. For example, the Bill points out that “[a]bundant and diverse communities of herbivorous fish are vital for coral reefs to recover from events like the recent unprecedented coral bleaching that occurred throughout the State. Without herbivorous fish, the long-term stability of these fragile ecosystems is in jeopardy.”

Fisheries managers and scientists say they couldn’t agree more. In fact, they think a lot more needs to be done in this regard. The unilateral focus on the aquarium fishery, however, is, according to those same fisheries managers and scientists, misguided. “A key element is sustaining robust herbivore populations,” says Dr. Walsh, “is to have a sufficient number of Marine Protected Areas, which protect such species from all harvesting.”

West Hawaii is the State’s largest aquarium fishery and includes a network Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and Fish Replenishment Areas (FRAs) off limits to aquarium fishing. The dots represent West Hawaii Aquarium Project survey sites. Credit: Walsh (2014)

The data show herbivore fish biomass is significantly higher (almost two times as much) in the West Hawaii MPAs than in the FRAs or the Open areas. In both the FRAs and open areas, largely unlimited non-aquarium fishing of herbivores such as parrotfishes and surgeonfishes is common. “Similar findings,” Dr. Walsh adds, “are also becoming apparent in Maui’s Kahekili Herbivore Fisheries Management Area.” There is currently no aquarium fishing there. Bottom line? To address the need for more herbivorous fishes on Hawaii’s reef, one needs to look beyond the aquarium fishery.

AQ Fishery’s Economic Value

Based on the state’s own numbers, the environmental effects of the aquarium fishery on Hawaii’s reefs are, at best, overstated in the preamble to HB 873. What about what the Bill has to say regarding the fishery’s economic value?

“Fewer than one hundred of the more than two hundred individuals with commercial aquarium fish permits are actually engaged in such activity and file reports with the department of land and natural resources,” states the Bill. “Most of these nearly one hundred aquarium collectors work part-time, collecting wildlife three days per week.”

The data show that in West Hawaii in FY2014 there were 51 commercial aquarium permit holders, and 41 of these reported aquarium catch that year. “Based on reported catch,” says Dr. Walsh, “approximately half of all permit holders appeared to work full time as aquarium collectors.” According to the data, there were also nine aquarium dealers on other islands who dealt with West Hawaii caught fishes.

HB 873 further downplays the economic value of the aquarium fishery, saying that the “part-time jobs appear to be the only identifiable economic benefit” of the trade. “Reported annual sales of less than $2,300,000 generate less than $100,000 in general excise taxes,” HB 873 states, claiming that is “far less than the amount of funding required for permit administration and adequate enforcement by the division of conservation and resource enforcement of the department of land and natural resources.”

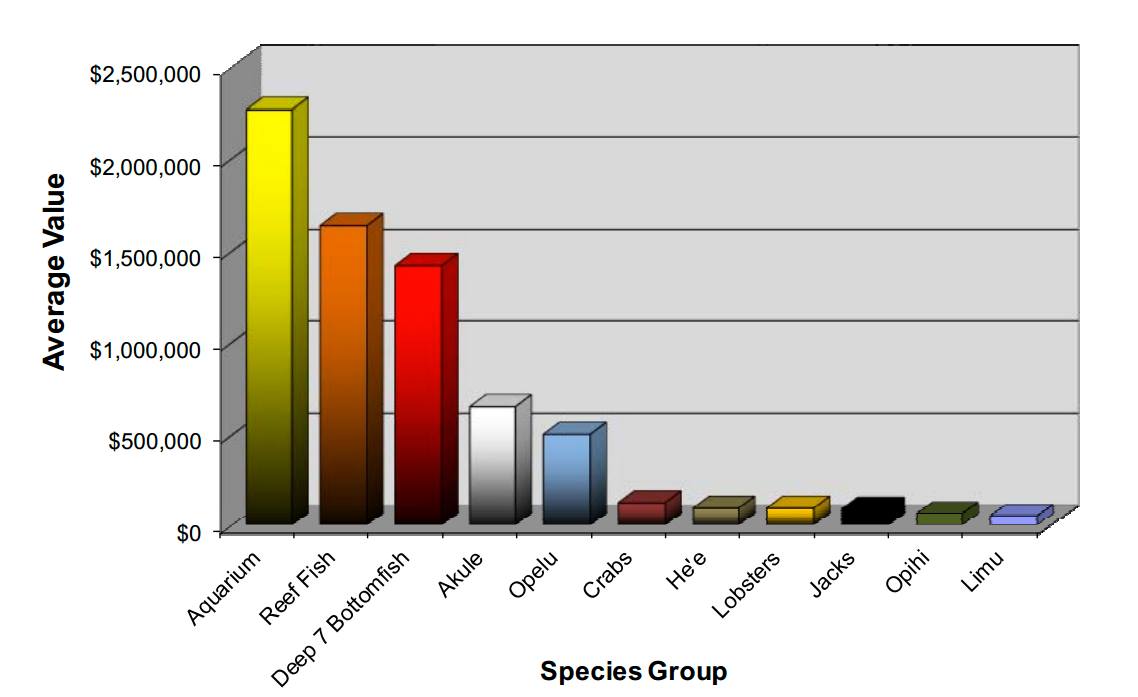

DLNR points out that, relatively speaking, all inshore commercial fisheries in the State of Hawaii are small scale. “The aquarium fishery is presently the economically most valuable commercial fishery exceeding other valued fisheries such as those for reef fish, bottomfish, akule, opelu and opihi,” says Dr. Walsh.

“Economic value for various inshore fisheries of the main Hawaiian Islands. Value ($ adjusted for inflation) averaged over FY 2012-2014” Source: Walsh (2014)

Reported aquarium sales figures cited in the Bill also only represent what is paid to the fishers and does not include value added by dealer and retail sales. Regarding the “funding required for permit administration and adequate enforcement by the division of conservation and resource enforcement,” it should be noted that fisheries management, permitting, and enforcement isn’t something that’s limited to the aquarium fishery. Aquarium fishers use the same fishing license as every other commercial fisher, and management and enforcement are equally applicable to a variety of fisheries statewide. The idea that the aquarium fishery should provide enough funds to cover resource management statewide seems odd.

Data: “Aquarium Fishery Can Be Fished Sustainably”

The preamble to HB 873 concludes with the following statement: “Wildlife left on reefs benefits the reefs. Restoring herbivorous fish populations is essential for the protection of Hawaii’s coral reefs and the current and future socioeconomic well-being of Hawaii’s people, which is tied to this unique marine environment.”

No one—not scientists, not fisheries managers, not fishers and not aquarists—is disagreeing, but is closing the aquarium fishery the solution?

Not only is the aquarium fishery not the environmental Bogeyman the Bill claims it is, but fishery advocates contend it is actually because of the aquarium fishery that so many good data and management measures exist at all. “The West Hawaii experience with the aquarium fishery points out the need for extensive monitoring, proactive management and especially the importance of having a network of protected areas,” says Dr. Walsh.

Overall, and based on the data, DLNR draws a very different conclusion than HB 873. DLNR maintains the data suggest management in the West Hawaii Regional Fishery Management Area is proving effective and that, overall, the State’s aquarium fishery can indeed be fished sustainably.

“Over a decade and a half of intensive monitoring data from the West Hawaii coast suggests that overall, regulations implemented under the West Hawaii Regional Fishery Management Area are successfully managing the aquarium fishery sustainability along that coastline,” says Deborah Ward, a DLNR spokesperson.

“DAR uses monitoring data to adapt regulations in response to changes in resource condition. At the end of 2013, DAR established a ‘White List’ that allows aquarium harvest of only 40 species within the WHRFMA. The data suggests that the State’s aquarium fishery can be fished sustainably provided we continue robust monitoring and adaptive management.”

Other Bills & Next Steps

In addition to the ban bills epitomized by HB 873, there are three other aquarium fishery-related bills before the Legislature this year in Hawaii. They are HB 511, HB 883, SB 670 and SB 1340.

Of these four bills, one (HB 511) would give aquarium fishers and others fishing in the marine environment more explicit protection against individuals who may intentionally or unintentionally harass them. The other three bills are all bills that would affect how aquarium fishes (and other animals in the case of SB 670) are treated during collection, holding and shipping. All three generally lack scientific support for some or all of the proposed practices, and individuals ranging from fishers to scientists to experts with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) believe some the proposed practices would likely be detrimental to the animals in question. CORAL Magazine will cover these bills in a future article.

Thursday (January 29, 2015) was the cutoff date for bills to be introduced to the 2015 Hawaii State Legislature. All but one of the seven aquarium fishery-related bills have been referred to committee (SB 1340, the last bill to be introduced, had not been referred to committee at the time this article was written), and the opportunity for public comment has begun. For information regarding how and when to comment, please have a look at the recently published article, and stay tuned for updates here at CORAL Magazine.

In the final equation, mainland aquarists and those around the world may want to keep in mind that what happens in Hawaii may not necessarily stay in Hawaii.

While the Hawaii aquarium fishery still has plenty of room for improvement, it remains one of the best-studied and best-managed aquarium fisheries in the world. The data consistently show sustainability, and the multi-stakeholder process that has helped shape fisheries management in West Hawaii is a model that should be applauded and studied for its utility elsewhere.

If the Hawaii aquarium fishery were to be shut down by legislative efforts unsubstantiated by the best available science, aquarists should worry about the health of the trade and hobby globally. In the bigger picture, all stakeholders in Hawaii’s reefs should be concerned when an emotionally-driven political agenda of a few hijacks a far larger and more important discussion about fishery sustainability and the overall health of coral reefs in the face of an honest analysis of the threats.

I would suggest consideration of establishing commercial marine sanctuaries in Hawaii that will increase fish habitat and populations dramatically while providing aquacultured live rock for the trade. Such is our practice in the Florida Keys for 20 years now.

Timothy, would you care to elaborate further on your concept of a “commercial marine sanctuary”? I should note, live rock and coral are not currently harvested from Hawaiian waters at all (it’s prohibited) – are you suggesting the state provide “safe refuge” for propagation and extractive fishing in designated “commercial zones”? If so, I’m not really sure if that’s all that far off from how things are already managed…eg. areas that aren’t part of MPAs and other reserves are effectively the designated places where commercial activities can take place. I’m guessing there’s more to your thought than what you posted…hoping you will come back and elaborate further!

Thank you for your suggestion Timothy. I suggest that you read the article before commenting.

The islands already have multiple (and large) Marine Protected Areas (MPA) that are federally protected around every island. There are also additional Fish Replenishment Areas (FRA) implemented by the state specifically for the aquarium fish species.

It’s important to remember that Hawaii has THE MOST managed and regulated aquarium fishery in the world. That includes Florida…

as a wholesaler in France for pet industry , I would like to say that we are very sensitive to sustainable trade…It is our economic interest and our turnover and jobs depend of it.

ALL IMPORTS FROM HAWAI ARE A MODEL FOR QUALITY: ALMOST NO LOSSES ON ARRIVAL ,PERFECT RESISTANCE AND ACCLIMATATION .

Protection and sustainable trade MUST work together.

Excess regulation will kill human biotope , exporters AND importers !

I live in Kapoho, near the easternmost point of the Big Island, next to the Waiopae marine conservation zone established in 2003. The nineties where the worst period for our coastal ecology. Before, we had two sea cucumbers per square foot in the inter tidal zone. After, we have none inter tidal and could swim 100 yards without seeing one. During this period aquarium fishing was opened up and quickly depleted the popular aquarium fishes. The yellow tang disappeared. In fact there where no yellow fishes left at all and their absence lasted over eight years. In your analysis, comparing our present fishery with what we had late nineties is using the worst, most depleted time as your standard. The increasing numbers are recovery, not abundance. Also comparing aquarium takes to food fish takes by weight is ludicrous. Yes, replenishment zones are essential to all sides of this discussion.