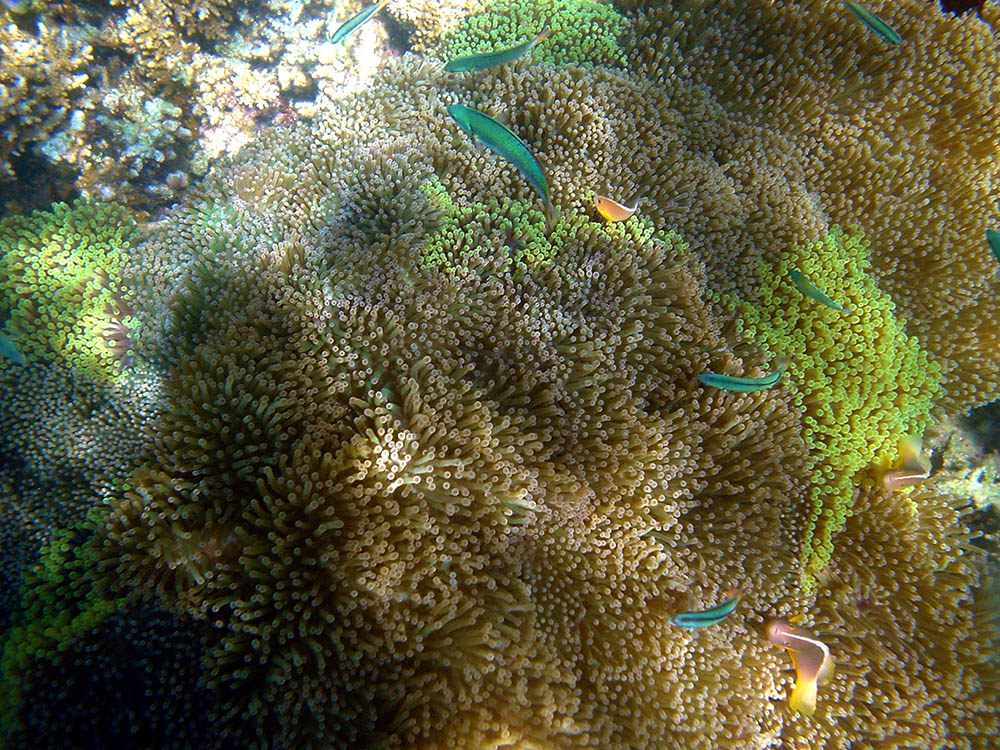

Typical Brown Saddleback Clownfish, photographed in Cebu, Philippines, by Flickr user Shinji | CC-BY-2.0

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

Geographic Variants Within the 30 Current Species of Clownfishes – The Saddleback and Skunk Complexes

Considering the prior observations of Anemonefish enthusiasts, and surveying the observed geographic variants of Anemonefishes by Matt Pedersen

Saddleback Complex

Amphiprion latezonatus – Kylie Waldon suggested that there was a color difference between Latezonatus found on the mainland vs. those at Lord Howe Island. Looking at her illustrations, it actually appears that she simply did not understand the differences between juvenile and adult coloration in the species.

A captive bred F1 juvenile Amphiprion latezonatus, reared by Karen Brittain in Hawaii, showing the typical juvenile pattern which includes a yellow-orange tail. Image by Matt Pedersen

A mature A. latezonatus has a dark tail with a white edge. Captive-bred Latezonatus like this specimen are prone to misbarring, and when they do, typically a white saddleback midstripe is what remains as seen here. Image by Matt Pedersen

Fully-barred Amphiprion latezonatus are a truly singular beauty, showing off their namesake markings, including Blue Lipped, and Wide-Band Clownfish. Image by Sustainable Aquatics.

Amphiprion polymnus – there are at least three distinct forms of Saddleback Clownfish in the trade, and it should be noted that host-induced melanism is well documented in this species.

#1. The classic brown form, with a true white saddle, is the type I grew up with and is well documented from the Philippines, and probably occurs in other locations as well.

Another look at the typical Brown Saddleback clownfish, photographed here in Puerto Galera, Mimaropa, Philippines, by Andrew Smith (image has been cropped) | Flickr | CC BY-SA 2.0

#2. A second black form, often erroneously imported as “Black Percula” from certain exporters, also comes from the Philippines. Some suppliers suggest this form is specifically found in Cebu. Barros documents this form also occurring in Lembeh Straits, Indonesia and further digging revealed documentation in Bali and Sulawesi. This Black form has a complete and narrower white midstripe vs. a wide saddle-shaped mark. The Black Saddleback Clownfish also has a white caudal peduncle stripe and bright yellow pectoral fins in juveniles. Breeding with this form has proven it to breed true, strongly suggesting this is a genetically-based variation of the species and not host-driven melanism.

![The Black Saddleback Clownfish, shown here in Bali, Indonesia, has a full mid stripe and a tail stripe (absent in the brown form). Image [croppped] by Flickr user jeff~ | CC BY 2.0](https://www.coralmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/10403736664_0702822105_o_1000w_cropped.jpg)

The Black Saddleback Clownfish, shown here in Bali, Indonesia, has a full mid stripe and a tail stripe (absent in the brown form). Image [croppped] by Flickr user jeff~ | CC BY 2.0

Black Saddleback A. polymnus, shown here in East Timor. Note the complete mid-stripe and the presence of a caudal stripe, absent in all other saddleback variants. Image by Nick Hobgood | Wikimedia | CC BY-SA 3.0

The Black Saddleback Anemonefish, shown here at Tasik Ria House reef, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Image by Jens Petersen | Wikimedia | CC BY-SA 3.0

#3. A third form, that with a black body and yellow chest and again the classic saddle-shaped midstripe, is found in Papua New Guinea. It is quite possible that this form might also be found in the Solomon Islands, although that is speculation only at this time. This form is currently one of the most desirable forms, but also one of the most infrequently seen.

The yellow-chested variant of Amphiprion polymnus, this individual from PNG. Image by Matt Pedersen.

#4. Here Yuri Barros and I may disagree; Barros believes that the form of A. polymnus found in Thailand represents a unique subpopulation of A. polymnus. To me, these simply look like melanistic individuals of the first, brown group. Still, it does seem that only dark-colored individuals show up in Thai diving photos; brown forms do not seem to be present. Whether this is host-driven melanism or a distinct genetic population (or both) is up for debate.

A version of the Saddleback clownfish, seen in Thailand, is patterned the same as the Brown form from the Philippines, but seems to be routinely all-black. This individual photographed around Ko Tao, Thailand, by “Amada44” | Wikimedia | CC BY-SA 3.0

Amphiprion sebae – when seen side by side with A. clarkii, there is no confusing these two species, yet the misidentifications continue to this day. The true A. sebae is found in the Indian Ocean, with populations reaching eastward into Bali where it can even be seen side by side with it’s relative A. polymnus, and even the erroneously-called “Sebae” representatives of A. clarkii.

Captive bred true Amphiprion sebae are becoming more widely available. This one from Sustainable Aquatics.

The true Sebae Anemonefish appears to be a pretty uniform species with no geographic variants that I can personally recognize and pin down. There is mild variation within the coloration of this species – some individuals may show black centers on the caudal fin, particularly as juveniles. Typically A. sebae exhibits yellow lower fins (see examples #1, #2, #3), although in some specimens the yellow on the lower portions of the body and caudal peduncle may be replaced with black, purported to be a host-induced melanism (such as this specimen in Java).

Another example of captive-bred A. sebae, showing the classic two-tone coloration and more elongate polymnus-complex body shape this species is known for (and which helps easily separate this species from A. clarkii). Image by Sea & Reef Aquaculture.

The Skunk Complex

Amphiprion akallopisos – With occurrences spread throughout the Indian Ocean, including far flung locales like the Seychelles and the Comoros off Africa’s east coast, it is surprising that there are no known geographic variations of A. akallopisos at this time. It is almost impossible, however, to visually differentiate this species from the look-alike Amphiprion pacificus.

Amphiprion akallopisos, photographed in Thailand by Bernd – Wikimedia | Creative Commons

A. akallopisos off the coast of Madagascar – image by Brocken Inaglory | Wikimedia | CC BY-SA 3.0

Amphiprion leucokranos – this “species” (hybrid) can show “variation” but this isn’t geographic in nature. Instead, I believe the variation is due to the genetic reshuffling that occurs due to its hybrid origin. Its known range of occurrence is limited to where the parental species, A. sandaracinos and the Black-footed forms of A. chrysopterus, reside; basically the Solomon Islands and the New Guinae land mass (PNG and Indonesian Papua). Gainsford has documented a full range of phenotypes with fish leaning towards A. chrysopterus but many more leaning towards the A. sandaracinos parent (see this example of A. x leucokranos and A. sandaracinos cohabitating in Papua, Indonesia). With wild-sourced Whitebonnets, one should expect some variation between individuals (see also Part II of this series), and variation is well documented now within the captive-bred offspring of these fish (see examples from ORA). A recent report of this “species” occurring in Java proved inaccurate; the fish were simply collected in Papua, and then brought to Java for exportation.

A stunning example of A. x leucokranos, illustrating why the hybrid has earned the trade name White-Bonnet or White Cap Clownfish. Image taken in Walindi, Papua New Guinea, by Michael McComb | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

A captive-bred, F1 example of A. leucokranos, produced from wild parents by ORA, demonstrating the typical lack of body stripes seen in this hybrid. Image by ORA

Amphiprion nigripes – the Blackfooted, Black Foot, Rose, or Rose Skunk Clownfish does show some variation in coloration, but these variations are not suspected geographic in nature since the fish hails from the Maldives. References also suggest occurrences in Sri Lanka and other islands off the coast of India, but currently I can find no photographic evidence to support that.

Amphiprion nigripes photographed March, 2006, in Fihalhohi, Maldives – image by Jandrek – Wikimedia

Another look at A. nigripes in the Maldives by Ewa Barska – Wikimedia | Creative Commons

Another pose of the Rose or Black-footed Clownfish in the Maldives – image by Neville Wootton | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

An individual A. nigripes with a highly-reduced headstripe, also recorded in the Maldives. Image by Jon Connell | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

Amphiprion pacificus – there are no known variations within this species at this time, and given a presumably small geographic range (Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Wallis Island) no biogeographical variation would be expected.

Amphiprion pacificus, direct from Walt Smith Interantional in Fiji – knowing where the fish was actually collected is just about the only way to know you have this species, and not A. akallopisos. Image by Matt Pedersen

Amphiprion perideraion – the Pink Skunk Clown does show some variation in coloration; whether these variations are tied to geography is a matter requiring further investigation.

A typical Pink Skunk Clownfish, this one photographed at Steve’s Bommie, Queensland, Australia, by Matt Kieffer (image has been cropped) | Flickr | CC BY-SA 2.0

Another classic example of the Pink Skunk Clownfish photographed off Cairns, Australia, by Teddy Fotiou | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

The Pink Skunk Anemonefish, shown here at Bunaken Island, Indonesia. Image by Flickr user Rob | www.bbmexplorer.com | CC BY-SA 2.0

It does appear that specimens of A. perideraion with more orange-based coloration are found in Fiji and Vanuatu; these are commonly referred to as “Sunkist” and apparently these variations do breed true to form. There has been suggestions that both more typical “pink” and the more desirable “orange” forms are both found in Fiji (and I’ve received both forms sold to me as originating from Vanuatu). While nothing has been firmly established, at this time, suggestions of habitat location may be linked to color forms. This suggestion also causes me to speculate; could different habitats offer different hosts, and then, could the coloration be in any way tied to host anemone species? The nature of coloration and possible variation in of A. perideraion coloration is an area open for further investigation.

A yellow-orange individual of Amphiprion perideriaon swims above a smaller and seemingly more traditionally pink-colored specimen. These fish were phtoographed in Fiji; some may call the top fish a”Sunkist” variant; will the smaller fish change over time? Image by Derek Keats| Flickr | CC BY 2.0

A more typically colored Pink Skunk Clownfish pair, photographed at Waiyevo, Northern, Fiji, still shows a more orange base coloration. Image by Barry Peters | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

A freshly-imported specimen of bright-orange A. perideraion, exported from Fiji by Walt Smith International. Image by Matt Pedersen

Captive-bred Fiji Sunkist Skunk Clownfish are now produced commercially by Sustainable Aquatics and others. Image by Sustainable Aquatics.

In addition to the Sunkist type color variants, a “magenta” form has been shown off by a retailer at one time; I openly speculated as to whether the fish had been dyed (a practice common with some freshwater fish) although a wild photo from the Coral Sea shows a very magenta individual living side by side with more normally colored forms. Could there be genetic mutations behind the various “shades” of A. perideriaon? It’s certainly worth investigation.

It has been noted that some forms of Pink Skunks have orange bars on the top and bottom of the caudal fin; this has at times been suggested as a trait of a male, but I cannot confirm nor deny that statement.

Amphiprion sandaracinos – I am not aware of any geographic variations within this species at this time; for that matter I’m unaware of any variations within the Orange Skunk Clownfish. Individuals from the Solomon Islands or New Guinea region may show aberrant patterning, but this is likely due to the ongoing hybridization of this species with A. chrysopterus. Presumably such aberrant individuals are specimens with low-level remnants of mixed DNA from past hybridization and subsequent back crossing to the A. sandaracinos parent.

Amphiprion sandaracinos, the Orange Skunk Clownfish, photographed in Cebu, Philippines, by Per Edin | Flickr | CC-BY-2.0

Amphiprion sandaracinos photographed at Panglao Island, Phiippines, by Silke Barron | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

Amphiprion thiellei – since so few specimens have been found in the first place, it is difficult to say whether there would be any geographic variation. Barros documents wild photos from three recurring locations; Cebu Island and Balicasag/Bohol Island in the Philippines, but also reports an occurrence from Menjangan Island to the northwest of Bali Island in Indonesia. Barros also points to a couple online images showing A. theillei residing with A. ocellaris; an interesting observation given the suspected ocellaris parentage proposed by some (being A. ocellaris X A. sandaracinos). Given the very small geographic footprint, combined with the highly suspected hybrid origin, most likely the variations we may see in patterning or coloration are due to the suspected hybrid nature of the species.

A stunning example of Amphiprion thiellei, the suspected hybrid between Amphiprion sandaracinos X A. ocellaris. Image by Bob Fenner | Wet Web Media

Continue to the next segment; Geographic Variants of Clownfishes in the Tomato Species Complex

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

Photo Credits – all photos as credited in their captions.