The next generation of Lightning Maroon Clownfish, progeny of a F1 Lightning Maroon mated to an unrelated, Wild (F0) PNG White Stripe, produced by Sea & Reef Aquaculture.

This is an expanded online version of the Reef News article first published in the print and digital editions of the July/August 2014 issue of CORAL Magazine.

I would like to call this news shocking, but truthfully it was anticipated and expected among the marine fish breeding community. As of June 12th, 2014, Soren Hansen of Sea & Reef Aquaculture, based in Franklin, Maine, disclosed exclusively to Coral Magazine his hatchery’s success in producing a second generation of Lightning Maroon Clownfish [described by some as the most remarkable and unusual wild clownfish ever collected – Ed.].

This news comes only months after Sea & Reef’s announcing the release of F1 Morse Code Maroon Clownfish, raised independently from wild White Stripe Maroon Clownfish collected in the waters of Papua New Guinea (PNG). Aquarists will be able to see Sea & Reef’s very first PNG Lightning Maroon Clownfish displayed at this year’s Mile-High MACNA Conference in Denver CO., August 29-31, 2014, where Sea & Reef will be in attendance (booth 629). Hansen anticipates that the first Lightning Maroon Clownfish will be shipped to retail pet stores in September, 2014.

Wild Lightning: It all started in PNG

New aquarists and readers may not be familiar with the back-story of the PNG Lightning Maroon Clownfish; in short, a Maroon Clownfish (Premnas biaculeatus) showing unusual branched barring and a reticulated head band was first discovered by marine fish collector Steve Robinson in 2008 in the waters of Papua New Guinea. The fish was dubbed the Lightning Maroon Clownfish due to similarities between the striped markings on the flanks and our typical idea of what lightning bolts look like.

The first and original “Lightning Maroon Clownfish”, collected in 2008 – image courtesy Steve Robinson.

Details are varied, but in short, it is generally believed that this first fish did not survive in captivity and was never brought into captive-breeding efforts.

A second fish, even more strikingly patterned, was collected by PNG diver Stephen Paul, working with the SEASMART program in 2010.

The second Lightning Maroon Clownfish made its way from PNG to importer/wholesaler Pacific Aqua Farms and retailer Blue Zoo Aquatics, both based in Los Angeles, California. Ultimately, this second wild fish did survive, was purchased by me and was delivered to Duluth, Minnesota. This fish was ultimately paired with a wild White Stripe Maroon Clownfish from the same PNG location, and successfully spawned in June, 2012. The second spawn, laid on June 21st, 2012, was the first to produce viable offspring.

The 2nd spawn of Lightning Maroon Clownfish in captivity, which produced the first viable F1 offspring.

First Lightning revelations

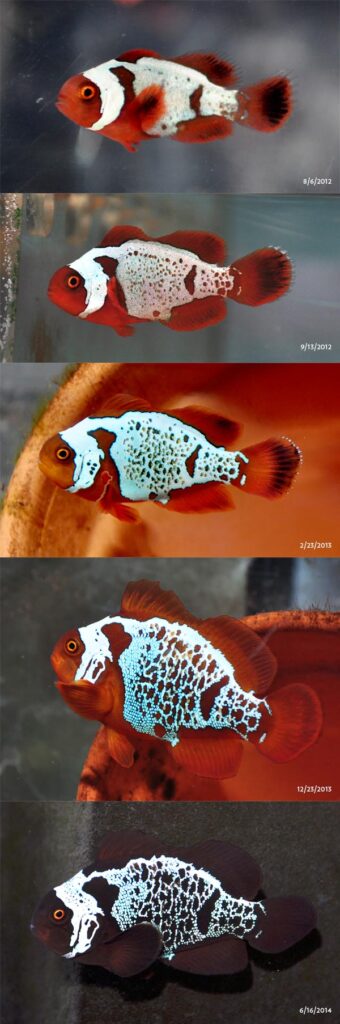

Pattern development in a F1 Lightning Maroon Clownfish, starting at 6 weeks post hatch, ending at 2 years post hatch. A 2-year-old Lightning Maroon Clownfish appears much closer

in pattern to the “wild” fish—proof that pattern changes and

emerges over years.

The offspring from the Lightning Maroon X White Stripe Maroon Clownfish pair quickly demonstrated a 50/50 split of phenotypes (outward visual appearance) upon settlement. Approximately 50% of the offspring consisted of traditional wild-type White Stripe patterning, as well as a subset of fish having extra white spots, dashes, or branches, a phenotype that is now generally referred to as “Morse Code”. The other 50% of the offspring were clearly “over-barred”. Their pattern initially started as a large blue-white dot on the top of the head which became visible during settlement, and newly-formed bars that were significantly thicker, wider and irregular in shape when compared to typical White Stripe patterning.

The initial appearance of these over-barred Maroon Clownfish offspring is similar to the initial appearance of the “Picasso” mutation seen in Amphiprion percula. The young offspring start out looking nothing like the wild Lightning Maroon, which caused aquarists to question whether these offspring were indeed genetically similar to the wild Lightning Maroon, whether they would ever “look” like a Lightning Maroon, or if they represented some different genetic outcome altogether.

Over the following two years, ongoing observation and documentation has revealed an amazing discovery; these solid white patches develop pinholes and spots of red coloration that grow and enlarge over time. As the fish mature, the pattern continues to evolve and morph in the direction of the mother’s pattern. This suggests that at some point the F1 offspring will arrive at patterning comparable to their mother (the wild Lightning Maroon).

This observation, combined with the continued evolution and reduction of the wild parental Lightning’s pattern over the last four years, ultimately suggests that the appearance of a Lightning Maroon Clownfish will fluidly change over the entire course of its lifetime, progressing from solid white markings, to pinholes of red, to equal parts red and white, to the classic white lacy appearance, and perhaps ultimately to an old Maroon clownfish showing very little white patterning at all.

The first (independent) genetic proof

In 2013, the first offspring from the successful 2012 brood were released via public eBay auction, spearheaded by Blue Zoo Aquatics. While bidder’s identities were kept strictly confidential, I can now confirm that Sea & Reef Aquaculture was the bidder who obtained a F1 PNG Lightning Maroon Clownfish with the identification “LM12”. This fish was paired with a wild (F0) PNG White Stripe Maroon Clownfish obtained from PNG sources a couple years ago; the Lightning Maroon played the male role in this pairing, in contrast to the female role of the F0 Lightning Maroon in the wild pairing.

At this time, Sea & Reef has confirmed that this next generation resulted in a roughly 50/50 split once again; the pair in Maine producing roughly 50% White Stripe / Morse Code offspring, as well as 50% Lightning variants. Sea & Reef’s transparency in reporting its breeding results raises some interesting questions and ideas.

Sea & Reef’s introduction of commercially cultured “PNG Morse Code Maroons” further demonstrates the unique genetic makeup of Maroon Clownfish found in Papua New Guinea.

The Morse Code Maroon

From a phenotypic standpoint, PNG White Stripes tend to have very thin white stripes, which generally are not bordered by black, which makes them stand out a bit when compared White Stripe Maroons from other locations. It seems that the “Morse Code” patterning is also a characteristic of the wild PNG fish, and perhaps tied to the PNG lineage more so than all White Stripe Maroons from other locations. Given the recurrence of the “Morse Code” phenotype in all known PNG matings to date, some are speculating that there is something genetic at play.

A clear look at the PNG Morse Code phenotype seen in offspring from multiple PNG Maroon Clownfish pairings.

Such spotting and barring was first noticed, and is often seen, in the offspring of normally-barred Gold Stripe Maroon Clownfish (GSM for short). Gold Stripe itself is at minimum a separate geographical variant, with almost every record pointing to Gold Stripes as hailing exclusively from Sumatra. However, recently it has been suggested that there might be Gold Stripes found in Melanesia, and one Philippine exporter reporting that roughly 5% of Maroon Clownfish collected in the Philippines are of the Gold Stripe variant (whether these represent other unique forms or possible human-introduced populations is a question for another day). Generally speaking, some have suggested that the Gold Stripe should be considered a distinct species from P. biaculeatus, with the currently synonymized P. epigrammata being applied to Gold Stripe Maroons.

Regardless of the species status, the occurrence of this spotting and barring in Gold Stripe Maroons has led to the moniker of “Gold Flake” Maroons as first coined several years ago by Sustainable Aquatics. It wasn’t until ORA started pursuing the breeding of these aberrant fish with vigor that other unusual forms emerged, particularly the all-yellow-with-red-fins Gold Nugget Maroon Clownfish.

Seeing the Morse Code phenotype occurring in multiple PNG pairings, particularly within fish whose parents don’t show it, and seeing similar patterning in Gold Stripe Maroons, suggests a connection. With the rumors now starting that there is some genetic component to “Gold Flake”, that further suggests that there could be a solid genetic basis for these subtle embellishments to the basic 3-stripe patterning of the White Stripe Maroon Clownfish, particularly in those fish hailing from the PNG location.

Heredity and Expression of the Lightning Gene

Whether you wish to call Sea & Reef’s Lightning Maroon Clownfish F1, or F2, is a matter of open debate – either way they represent both an outcross to an unrelated line, in this case a wild outcross (which many would easily call F1), and they represent the 2nd generation away from the wild for the mutant gene (which some would more likely considered F2). Both aspects of the cross parentage are noteworthy. The fact that the gene has made it a second generation clearly indicates the heritable nature of the gene itself. The fact that the Lightning Maroon parent was a male, not female, rules out any notions of sex-linked heredity (and is one more nail in the coffin to the apparently hobbyist-originated baseless notion that one sex imparts pattern while the other sex imparts coloration to Clownfish offspring).

Seeing the presence of Lightning Maroon phenotypes in the Sea & Reef outcross also provides a compelling piece of evidence in the search to determine the expression pattern of the mutant gene. Many hold out hope that the Lightning expression was a recessive trait, like Albinism, which would mean that both parents must have and contribute the gene to their offspring to create more Lightnings. In part, some breeders are betting that the White Stripe siblings from the F1 Lightnings would have to carry such a hidden gene, a hypothesis I have strongly downplayed and discouraged, but cannot fully eliminate yet. With the first mating and resultant 50/50 spread in the F1 offspring, all common types of genetic expression (Dominance, Partial Dominance and Recessive) were candidates provided this was a single-locus trait (one not controlled by multiple genes on multiple loci).

When considering the recessive trait hypothesis from a different angle, Hansen proposed the valid question, “If the LM gene is dominant or partial dominant with both males and female being able to contribute to the expression of the LM phenotype in the offspring, why is it that this genotype expression is so rare in the wild?” To simplify – if not recessive, we ought to see many more wild Lightning Maroons, not unlike how we’ve since seen numerous likely examples of Picasso genetics in wild A. percula.

With this second mating being an F1 Lightning to an unrelated F0 (wild) White Stripe Maroon from PNG, we must increasingly ask ourselves what are the odds that two wild, outwardly ‘normal’ fish, both happened to carry a hidden recessive gene that’s required to produce the appearance of Lightning? With the results of Sea & Reef’s breeding, I believe the already small odds just got even smaller. This second mating further supports my leaning towards dominant or partially-dominant forms of expression for the Lightning gene. Soren Hansen agrees with this notion and states “In my opinion what we have seen so far from the Lightning Maroon gene expression is that the mutated gene behaves in much the same way as the snowflake gene.” (The snowflake gene Hansen refers was first identified by UK-based Tropical Marine Centre (TMC) in A. ocellaris.)

The Snowflake Ocellaris – this particular specimen being considered a “Premium” grade fish by Sea & Reef.

Thankfully, multiple Lightning Maroon and sibling pairings are underway both in my own basement as well as the breeding rooms of aquarists around the country. Pairings include F1 Lightning X F1 Lightning, F1 Lightning X F1 White Stripe sibling, and F1 White Stripe Sibling X same, as well as at least one breeder recreating the F1 Lighting X F0 White Stripe pairing that was accomplished by Sea & Reef. The results from these additional matings will provide valuable insights into the genetic mysteries of this fascinating wild discovery.

The Lightning Maroon – Designer Clownfish Ombudsman

Designer clownfish remain a contentious aspect of our marine aquarium industry, and in some respects my own personal philosophies, again prominently shared, may have served to amplify those sentiments. I always espoused the belief that we must put emphasis on the wild biodiversity first, because if it is lost, it cannot be replaced. For a long time, I believed designer clownfish were the enemy, and they were never welcome in my aquariums.

The quandary presented by the fact that the Lightning Maroon was 100% wild in origin, representing some of the rarest “natural” biodiversity found, certainly gave me pause. It was almost with reluctance that I took on the breeding project, saying if the fish had been discovered in a tank, I would never have touched it.

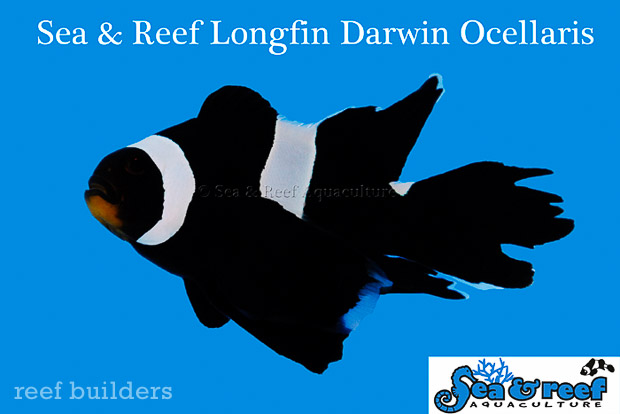

Of course, “Picasso”, the gene responsible for both Picasso and Platinum Perculas, was also first discovered in a wild fish as well. Other mutations, such as the nearly simultaneous yet independent discovery of a Longfin mutation in both Black Ocellaris (Sea & Reef Aquaculture) and the standard Orange version (Sustainable Aquatics), are actually commonplace across many families of freshwater fish, probably representing a common fundamental break in the gene that controls fin length.

Sea & Reef’s early 2014 discovery of a Longfin Black/Darwin Ocellaris literally came on the heels of the same phenotype being discovered in Orange Ocellaris by Sustainable Aquatics in late 2013.

Experience and expanded knowledge, particularly in light of breeders being transparent, forces me to reevaluate my formerly staunch opinions. Perhaps the origin of a mutation really isn’t the issue? Provided we have the understanding of how to control and manage that mutation, it’s easy to ensure a genetic escape route back to the natural form while also avoiding the overall degradation of the species in cultivation. In short – An albino longfin Ocellaris clownfish isn’t really a species conservation problem if you have the appropriate mates required to get back to a wild-type 3-barred orange Ocellaris.

While some may have glossed over the genetic insights, there is an important message to be considered – genetic mutations can be bred out. Soren Hansen and I both suspect that any mating of a PNG Lightning Maroon to a PNG White Stripe Maroon should produce the 50/50 split, showing both the “natural” wild type White Stripe, as well as the still rare, but a little less so these days, “Lightning” variation.

The Future of Lightning – Hybrids On The Horizon

What happens next for the Lightning gene? That remains to be seen. The largest and most obvious question is what happens when you mate two Lightning Maroons together. Do we simply get 100% Lightning Maroons, or do we get something entirely new? I suspect this thought-provoking question will be answered in a year or two.

While genetic mutations within a pure species are generally easily controlled, the same cannot be said for hybridization. Hybrids, by their very nature, represent a mixing of genetics between species that cannot be undone. Both Hansen and I believe that there will be breeders eager to inject the Lighting gene into other designer clownfish lines that already exist. This could be very detrimental to the captive population of Lighting Maroon Clownfish, particularly those raised in the future by hobbyists vs. commercial producers who understand the importance of maintaining clean lines.

One of the most obvious “hybrid” candidates is the crossing of a Lighting to a Gold Stripe Maroon, and this is one of the crosses I am most vehemently opposed to on the basis that it will not create the “Gold Lightning” that one expects, but will serve to muddy the clear distinction between what are currently two easily distinguishable forms of Maroon Clownfish. Pursuit of such a hybrid may present dire consequences for the PNG lineage which breeders like Hansen and I are striving to keep pure.

With the rise in prevalence of Maroon X Ocellaris-type hybrids, in conjunction with the ubiquitous availability of hybridized forms consisting of Amphiprion percula, A. ocellaris, and the all-black A. ocellaris “Darwin” (which again, some believe to be a distinct species), it will probably be only a matter of time before someone tries to bring the Lightning gene into this generally disorganized and murky genetic cocktail.

I, like most veteran freshwater breeders, have a firm understanding of the dangers that hybrids pose to species preservation in captive breeding. One of the long standing and valid concerns is that designers of all types may displace wild forms. From Hansen’s point of view, “In some respect the designer clownfish craze is taking away the focus of bringing more wild type fish in culture. However, on the flip side the higher income from designer clownfish also allow hatcheries more resources that can be used for [research and development] of more wild species.”

However I’ve also come to realize it’s foolish to think that we can stop hybridizing from happening, and as Hansen points out, “hatcheries will raise what the market want to buy.” Therefore, I will strongly encourage transparency in any hybridization attempts; Dr. Sanjay Joshi is a prime example of operating with beneficial transparency in regard to his Photon Clownfish assemblage–we’ve learned key in areas of stripe formation and genetic influence as a result of his thorough documentation.

I’ll also strongly suggest that the more disparate the species involved in a hybrid, the better. While Gold Stripe X Lighting Maroon is highly likely to cause major problems in the future, if someone can actually breed something like a Lightning Maroon Clownfish hybridized with a Galaxy Clarkii Clownfish, the odds are very slim that we’ll be able to confuse it for any natural species!

How will commercial and private marine fish breeders utilize the increasingly available Lighting gene?

Increasing availability of the Lightning gene as a result of commercial production ensures it will be the one of the next genes thrown into the designer soup. Ultimately, the guppification of clownfish will continue – it is inevitable and it is quite exciting, particularly for breeders who aspire to easily make a name for themselves (it’s much easier to make a new clownfish cross than to breed a new species for the first time). Since we cannot stop this from happening, even if we’d like to, it’s better to have a collective dialog and guide with a gentle hand where possible, and to look for ways that purists, and designers, can coexist.

Image Credits

Steve Robinson

Soren Hansen – Sea & Reef Aquaculture: http://www.seaandreef.com/

Matt Pedersen – The Lightning Project: http://www.Lightning-Maroon-Clownfish.com

Trackbacks/Pingbacks