As the catastrophic spread of Indo-Pacific lionfish continues in Western Atlantic and Caribbean waters, Florida legislators propose new laws to stop aquarium-trade importations

By Ret Talbot

Images courtesy of REEF

I remember seeing my first lionfish in the wild. It was on a fairly degraded reef in less-than-sparkling water within site of the capital of a small developing island nation. We’re not talking the type of water clarity you see in the live-aboard brochure or on National Geographic specials. I recall feeling not at all at ease—the chaotic boat traffic, copious flotsam, ghost fishing gear, and the murky conditions. In the back of my mind, I was thinking about the lack of shoreside diver support—heck, this country didn’t even have a tourist industry, much the less dive tourism.

The small pack of lionfish emerged from the shadowy confines of a coral head rising up from a silt bottom. They were, undoubtedly, majestic but also (I’ll admit now) a little intimidating. Otherworldly perhaps—their spines jutted out like arrayed plumage on the many gratuitously gregarious tropical birds in the rainforested hills behind the low, hulking mass of the capital. The lionfish were at once beautiful and menacing. Majestic and predatory. Clearly “lionfish” is a good name, I remember thinking as I watched the nearest fish’s big eye lock on me. The animal posed absolutely no risk to me—I want to be clear about that—yet I still felt compelled to give it and its compatriots a wide birth.

I’ve seen many more lionfish in the wild since that first experience, and, like many divers, my attitude toward them has shifted somewhat. Seen in their endemic range throughout the Indo-Pacific, they still amaze me, but when spotted on a Florida reef or a wreck of the coast of North Carolina, they elicit an emotion more akin to rage. They don’t belong here, and yet they’re here in huge numbers and with no natural predators. Nobody really knows how many there are, but biologists will tell you there are enough to have already altered the ecosystem—to have severely impacted native fish populations. Lionfish in the Atlantic, throughout the Caribbean, in the Gulf of Mexico, and now established in both Columbia and Venezuela are synonymous with the terms like “injurious” and “invasive” when exotic, feral wildlife is discussed.

Is an Indo-Pacific lionfish loose in the tropical Atlantic really a problem?

Consider what has been published as peer-reviewed science. In the invaded range, lionfish are reaching sizes (almost 50 cm or 20 inches) much larger than in their native range and have been shown capable of reducing the biomass of the native prey fish community by an average of 65%—with some sites reduced by more than 90%.

A lionfish can consume prey larger than half its own body size, and more than 64 prey species have been documented from a single lionfish stomach. Lionfish reproduce year-round in the warmer portions of the invaded range with each female producing around 30,000 eggs per spawning event and as often as every 4 days or so. When confronted with these and other data, most observers agree the lionfish invasion constitutes a problem of massive proportions.

John Halas (Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary), left, and Lad Akins (REEF) with the first lionfish reported and removed from the Florida Keys in January 2009.

“An Expanding and Increasing Problem”

“We’ve been heavily involved in this issue for a number of years,” says Lad Akins, Director of Special Projects for Key Largo, Florida-based Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF). Founded in 1990, REEF is an organization composed of divers and other marine enthusiasts committed to ocean conservation through contributing to the understanding and protection of marine populations. REEF’s primary tool is essentially citizen science—volunteer fish monitoring and survey work that informs the work of scientists, marine park staff, and the general public.

“Lionfish were one of the non-native species that people started to report in their surveys,” says Akins, “but it really wasn’t until 2004, when we started seeing lionfish in the Bahamas, that we realized this was an expanding and increasing problem. We realized it had the potential to become something pretty serious.” Akins says that’s when REEF started doing more than just casual record-keeping regarding lionfish. Since then, REEF has been “seriously involved” in lionfish education, research and policy.

“Obviously we’d like the region to be lionfish free,” Akins says, although he’s quick to note that current efforts are really only focused on control. “We are finding that [control efforts] have been very effective, especially at the local scale.” In particular, recreational dive sites are showing real signs of improvement, he says. “Published peer-reviewed studies are showing that diver removals are having a very positive effect in keeping lionfish number down and allowing native fish populations to recover.”

The trouble is that those effective efforts are really only occurring at popular recreational dive sites. While innovative chefs with an eye toward environmental concerns have turned lionfish into a meal to be appreciated, it’s going to take a lot more lionfish tacos to solve the problem. Building recreational and commercial lionfish food fisheries have been a step in the right direction in harvesting lionfish, but a major problem is that the food fisheries target only the large specimens, while the diver removal focuses only on a limited number of sites. More is needed.

Lionfish Ban Bills

Akins is generally supportive of two identical lionfish bills introduced last week to the Florida Legislature. The bills, which are identical at this point with one filed in the House and the other in the Senate, would ban the importation and aquaculture of all lionfish within the genus Pterois.

Dr. Stephanie Green of Oregon State University documenting lionfish populations, impacts and effectiveness of removal efforts in the Bahamas.

Akins likes the bills because they likely would address the portion of the lionfish population currently overlooked by fishers and recreational divers. Banning the importation of lionfish to the state would, according to many supporters of the bills, remove the primary source of lionfish introductions and encourage the trade in invasive lionfish. A lionfish ban and booming trade in Florida lionfish, so the bills’ backers contend, could create additional economic incentive to get the fish out of the water, while preventing gene pool enrichment from the Indo-Pacific. This would hopefully lead to an inbreeding bottleneck somewhere down the road that could prove wonderfully catastrophic to the invasive population.

The bills address a situation that has some people scratching their heads. You’ve heard the stories of the massive pythons in the Everglades eating their way through indigenous species, right? Some Florida natural resource agency officials, as well as legislators, see the lionfish in much the same light. Many simply think it is ludicrous that animals with the potential to do such harm are legally imported into the state for something as “trivial” as a hobby.

It is legal and common practice for marine aquarium trade operators in Florida to import large numbers of non-native reef species for the aquarium trade. The same is true for trade operators in other states, but, with the exception of Hawaii, none of those other states provide viable habitat for most invasive reef aquarium animals. In Florida, it is generally believed that while several vectors for the introduction of non-native marine life exist, the marine aquarium trade is one of the major sources. A 2009 NOAA publication documents more than 30 non-native marine fish species that have been spotted in Florida waters. Almost all of those are fishes commonly sold for aquarium use.

Some supporters of the two lionfish ban bills believe working with the aquarium trade on lionfish control initiatives could be very productive. In fact, the bills are drafted in such a way that aquarium fishers would be incentivized to harvest greater numbers of invasive lionfish. “Marine life collectors visit areas that are not dived by the recreational dive community,” says Akins, “and their efforts…can also help reduce the populations and impacts of lionfish in non-dived sites.” Further, Akins points out, the aquarium fishery would likely target juvenile lionfish, which both the emerging recreational and commercial food fisheries may pass over.

The Blame Game – What’s Wrong with the Bills?

The idea that a ban on importing or farming lionfish would provide enough incentive to make a dent in Florida’s invasive lionfish population doesn’t hold much water with with Sandy Moore, vice president of Florida-based Segrest Farms. Segrest is one of the largest aquarium trade importers in the country.

“I believe the bill to be well intentioned,” says Moore, “but the proverbial horse is out of the gate. We’ve purchased [Volitans Lionfish] out of Florida waters for almost three years, trying to do our part to eradicate this predator from our local waters.” According to Moore, Segrest started sourcing lionfish from the Florida Keys in June 2011, when the lobster fishermen started finding them in their traps. “I’m sorry to report we have not been able to overfish them for the aquarium trade.”

In addition to thinking the ban would not provide enough incentive to realistically deal with the problem, Moore worries about the premise behind the bills. “The bill assumes that the lionfish were introduced by land,” she says, “and not by ballast water.” Moore does not believe it is realistic to think that aquarium-keepers and others associated with the aquarium trade could be responsible for enough fish to create propagule pressure in the Atlantic. “Therefore,” she says, “the bill is flawed by its premise that the species was introduced by the aquarium trade.”

While some say the “how” of the lionfish introduction is really beside the point, others feel it is important to address the root causes of the so-called lionfish invasion, and not everyone agrees with Moore’s assertion that the aquarium trade is not to blame. As Moore points out, it’s been argued for some time that ship ballast water is to blame for the introduction of lionfish in Florida. In this scenario, a ship at an Indo-Pacific port within the native range of the lionfish takes on water for ballast and then pumps that water out once it reaches a destination port in Florida. Whatever was pumped in from the one biogeographic region is then pumped out in another, causing the introduction of non-native species. The ballast argument is so often repeated that it’s become a de facto truth for many, but the plural of anecdote is not data.

While ballast water, as well as shipping in general, has been shown to be the source of several well-documented introductions of non-native species—typically hull fouling organisms, the data do not support ballast water as the likely cause of lionfish introductions to south Florida.

“Ballast water is not thought to be a vector from the native range, as little shipping into South Florida comes from the Indo-Pacific,” says Akins, who has also heard the ballast water argument. “Most ships treat or exchange ballast water prior to entering nearshore waters, and lionfish are not likely to be introduced into ship bilges from their traditional habitat near the bottom, especially since the density of lionfish in the native range is very low.” Peer reviewed scientific literature is clear on this point, and larval fish experts scoff at the notion that lionfish larvae could survive the trip in a dark bilge.

Mixed Aquarium Trade Support of the Bills

Not everyone in the aquarium trade in Florida thinks the bills are misguided or need significant re-working. “I am personally in support of banning importation of all species [of] lionfish into the U.S.,” says Ben Daughtry, vice president of operations of Marathon-based Dynasty Marine Associates, Inc. Dynasty Marine supplies public aquariums, research institutions and pet stores with marine livestock from Florida and the Caribbean. While Daughtry is also vice president of the Florida Marine Life Association (FMLA), he says FMLA has not yet come out with an official position on the bills.

Other individuals involved in the aquarium trade nationwide have mixed views on the lionfish ban bills. Some of the concerns are simply the result of assumptions based on incomplete or mis-information. Some fear these bills represent yet another attack on the aquarium trade. As one aquarist said, “I think this is just like a chink in the armor. Once this legislation passes, it will make it easier for the next piece of legislation and on it will go until we no longer have a hobby.”

These concerns are raised almost one year to the day after many aquarists learned of the Invasive Fish and Wildlife Prevention Act (HR 996), a piece of legislation introduced into the U.S. House of Representatives by Rep. Louise Slaughter (D-NY). HR 996 aimed to create an “accepted” or “white list” of common domesticated animals that could be imported and kept legally in the U.S. A likely result, aquarists feared, would be that most animals kept by marine aquarists could be banned. HR 996 never made it out of committee, but many in the marine aquarium trade and hobby remain wary of any legislative initiative that could impact the keeping of reef animals.

Captured juvenile Pterois sp. lionfish, increasingly a target for aquarium trade collectors and “Lionfish Derby” diver competitions.

“Draconian” to Ban the Whole Genus?

There is a lot of support for the bills in Florida amongst people involved in any significant way with the lionfish issue. Nonetheless, there is a growing sentiment that some important changes need to be made to the language of the bills before they make it out of committee. Akins characterizes the most significant and common criticism when he says, “We would encourage the bill to be amended to only address the two invasive species of lionfish.” Many echo this sentiment. “I don’t think the intent is to restrict the import of any member of that genus even though that is the way the bill is written right now,” says Akins. “We would hope that it would be amended to reflect that we’re only addressing invasive lionfish.”

At present, only two of the ten species of lionfish in the genus Pterois are considered established and invasive in Florida waters. They are P. miles (commonly called the Common Lionfish, Miles Lionfish or Devil Firefish) and P. volitans (commonly called the Volitan, Volitans or Red Lionfish, although there is also a black color morph that is sometimes imported for the trade). Over 90 percent of the invasive population is made up of P. volitans. The remainder is made up of P. miles. The two species, especially as juveniles, are often misidentified in trade. Other lionfish in the genus that are available in the North American marine aquarium trade include the Mombasa Lionfish (Pterois mombasae), Russell’s Lionfish (Pterois russelli), the Radiata Lionfish (Pterois radiata), and the Antennata Lionfish (Pterois antennata).

Sandy Moore agrees with Akins that if the bills do move forward, they should move forward with a ban on only the two species already considered established and invasive. “Restricting all 10 species puts us at commercial disadvantage with out-of-state competitors,” she says. Segrest Farms is based in Florida but ships nationwide. “To restrict the other eight species, with no possibility of obtaining a conditional permit, is rather draconian.”

The Volitan is by far the most popular species of lionfish for aquarists with recent import data showing that more Volitans are imported for the trade than all the other species combined. Retail prices for juvenile Volitans often begin around $35 with almost twice that much being paid for the so-called Black Volitan. The other lionfish species currently established in Florida waters (P. Miles) can sell for twice what a Volitan costs. The Radiata Lionfish and the Mombasa Lionfish can both fetch upwards of $60-$70, while the Russell’s Lionfish and the Antennata Lionfish frequently retail for under $30. There has been some talk of selling Florida-harvested Volitan Lionfish at a price premium because they are the most sustainable option and may represent greater value to some consumers. It’s more likely, however, that if a ban goes into effect, Florida-harvested lionfish would sell for the same price or less than those imported from the Indo-Pacific, as bringing them to market does not require the same shipping costs but likely will involve higher labor costs.

In addition to the lionfish from the genus Pterois, lionfish commonly called dwarf lionfish from the genus Dendrochirus are also popular in the aquarium trade. Dwarf lionfish imports would not be impacted by the lionfish ban bills as currently written.

While Moore and Akins would like to see legislation restricted to only the two species that are currently causing the problem, Daughtry of Dynasty Marine says he believes listing the entire genus is a smart move. “These two species are spreading in such numbers that the trajectory is pretty scary and we haven’t seen it saturate anywhere yet at far as I know,” he says. “Who’s to say that the other species of lionfish wouldn’t have similar results?”

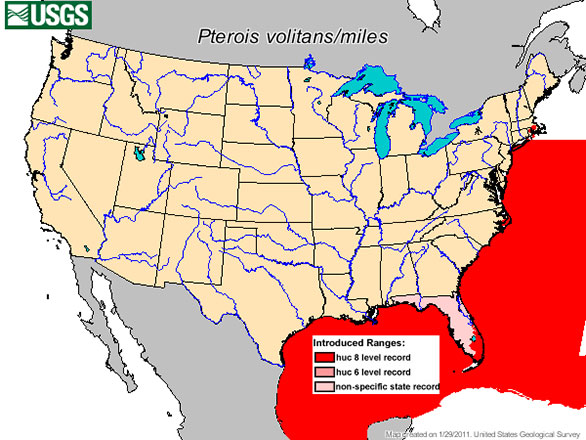

USGS map shows the range of reported lionfish reported captures stretching from the southern Caribbean to New England, where the Gulf Stream seasonally carries juveniles north.

About a decade ago, Forrest Young, founder and director of Dynasty Marine, sat on a Florida Department of Agriculture Task force which looked at the potential threat posed by marine exotic species. “Not one of the biologists there,” Young said, “including some fairly high-ranked State of Florida guys…predicted the extent of the spread of this species and the rapidity of the spread.” While Young has not read the bills yet, he agrees banning all of the species in the genus is probably a good idea.

“I’d agree to ban the import of any more species of lionfish until we are sure that the escapement vector for additional species and their ability to survive and reproduce here is not as risk prone.” Based on his experience rearing similar species of fish, Young believes any of the Pterois species could easily be as invasive as the Volitans.

Representative Holly Raschein (R-Key Largo), who brought the lionfish ban bill in the House of Representatives, believes controlling the invasive lionfish population in Florida is essential. “We’re called the dive capital of the country,” she says, alluding to the important dive tourism dollars, especially in her part of the state. Raschein is a vocal advocate for the growing lionfish food fishery, but she felt more needed to be done. While she acknowledges banning the entire genus is a valid criticism of her bill, she maintains that her bill’s approach is “a bolder move,” which will “cause less confusion.”

“Who’s to say,” she asks, echoing Daughtry and Young, “that the other species won’t become a problem down the road?”

Reportedly delicious, lionfish is appearing in US and Caribbean fish markets and is the subject of a number of new cooking guides, such as this offering from REEF.

Akins’ approach is more nuanced than both Daughtry’s and Raschein’s. “I think it comes down to singling out species that have never been found in Florida waters and the resulting impacts to the aquarium trade and to pet owner freedoms,” he says. “The only Pterois documented in the Western Atlantic have been the two invasive species.” Akins says he knows of no assessment conducted to date to determine the level of risk of the other members of the genus, even though several of them appear regularly in the aquarium trade.

“Restricting [non invasive lionfish species] from import simply because they are related to the invasive species could cause unwarranted economic impacts to the trade,” he says. “If we are going to restrict import of all Pteroids, then should we also look at other ornamental species or families in the trade that could cause harm and enact sweeping legislation?” This, of course, is the fear of some in the aquarium trade, a trade that has seen aggressive legislation aimed at seriously curtailing or even ending it in recent years. “If restrictions based on potential harm are going be made,” concludes Akins, “then they should be made equitably across the board and with solid information.”

Still Early in the Game

Now that the lionfish ban bills are in the legislative pipeline, it’s time for all stakeholders to get to know the bills and to comment on them. In addition to addressing the issue regarding whether the entire genus should be banned, many who have looked at the bills also believe some of the language concerning imports should be changed. For example, some argue it should be legal, if not encouraged, to import invasive lionfish harvested in Georgia or the Carolinas if that will help create incentive to collect them there. The same would be true with imports from other Caribbean countries with invasive populations of lionfish, such as Haiti.

Most advocacy and industry groups, as well as state agencies contacted for this article said they are not yet familiar enough with the bills to voice their support on the record. In off-the-record discussions with individuals representing key stakeholder groups, however, it seems clear at this point that there will be a lot of support for a legislative ban on lionfish imports and aquaculture. Two places where important opposition may arise may be from FMLA and the Pet Industry Joint Advisory Council (PIJAC), who both did not officially respond to inquiries before publication. Sources close to both of those groups expressed the potential for broader trade concerns beyond just needing to dot the i’s and crossing the t’s, but discussions are ongoing at this point.

How Much is Enough?

Years after my first wild lionfish encounter in the Pacific, I found myself talking to a spearfisher sitting on the gunwale of a skiff off the coast of Florida. “We killed it today,” he said, referring to the stringer of recently speared lionfish at his feet. “I just hope it’s enough,” and by “enough,” I took it to mean “enough to win.” Spearfishing tournaments targeting lionfish have become popular in recent years with awards and cash prizes for the biggest and most lionfish killed.

The bigger question is will it be possible to remove enough lionfish to reverse the ecosystem-wide effects of having an invasive species on the loose, especially one that has proven such an effective predator of native species. At this point in time, eradication remains little more than a pipe dream for most, but getting the problem under control seems a bit more realistic. Akins has pointed out how recreational divers have had a demonstrable impact on popular dive sites. Raschein believes commercial fishing for lionfish can become more efficient, and more can be done to build local markets for lionfish as food fish. Moore has said that Segrest Farms is already harvesting lionfish from state waters, and hopefully larger markets for Florida lionfish can be developed and cultivated.

Given this progress, some are left wondering whether we really need a ban on the importation of lionfish to Florida or whether it’s just window dressing. Given the huge numbers and breeding populations of invasive lionfish already established in the tropical western Atlantic and Caribbean, what good does a ban do? If the purpose of a ban is meant to address the aquarium trade as being the primary vector for the introductions, why not instead focus on more effective laws on the release of non-native species? “Make it a felony with a minimum fine of $10,000 and minimum one-year in jail,” suggests one aquarist, “and perhaps you would gain public attention.”

While Akins agrees in principle with stiffer penalties, he thinks the likelihood of catching someone releasing a non-native is pretty small. “It’s sad but true,” he says. “One thing the ban will do,” he continues, “is eliminate the potential of new genetic stock being introduced from the native range.” If no aquarium trade business or personal aquarist in Florida possesses an Indo-Pacific lionfish, the genetic stock in Florida waters will be limited, and Akins thinks this could be an essential component, along with an increased food and aquarium fishery, to getting the lionfish invasion under control.

Of course even with a ban on importation in place in Florida, that doesn’t stop an aquarist in Georgia legally buying, keeping and then (illegally) releasing an Indo-Pacific lionfish into the wild a stone’s throw north of the Florida state line. Perhaps that’s a discussion for another day.

CREDITS

Images courtesy of REEF (Reef Environmental Education Foundation) REEF.org

REEF Lionfish 2014 Derby Schedule

Invasive.org

Wonderful article. You really captured the diversity of opinions about this subject. Thanks!

Little late to ban Lionfish imports, isn’t it? They are already there en masse.

From the above article, “preventing gene pool enrichment from the Indo-Pacific. This would hopefully lead to an inbreeding bottleneck somewhere down the road that could prove wonderfully catastrophic to the invasive population.”

The invasion could be made worse if a public aquarium with open systems connected to the ocean breeds new lion fish which were imported in a display designed to show tourist about the issue. The newly imported fish could send larvae into the ocean and strengthen the genetic diversity of the local, currently inbreeding, populations. The same strength could come if a new ship dumps a ballast full of larvae that came from the Indo-Pacific.

Awesome article and a sad testament to the irresponsible actions of some in the aquarium hobby. The problem with banning imports of a certain species is that it won’t stop further introductions of others. As the anonymous aquarist in the article mentions, stiff penalties are in order for releasing any non-native species, aquatic or not. And pet stores should be required to post large signs and inform every purchaser of livestock as to the impact of release and penalties involved.

Darren I believe you are missing part of the point. It is not a fact that aquarium hobbyist are to blame for the Lionfish invasion, just one of many theories. It is possible that shipping companies and public aquariums could also be to blame.

Great analysis of a complex problem. The objective here is not to “punish” the aquarium trade (irrespective of whether or not it is the cause of the invasion), but to make it part of the solution. Research is confirming that active removals of lionfish in the invasive range does result in recovery of native fish populations. But for removal efforts to be successful (and more importantly, economically sustainable), a range of stakeholders need to be involved, particularly those that can reap commercial benefits (fishers, restaurants, etc.). Live capture for sale to aquarists is another vertical market that meets this criteria. What isn’t clear is whether importation from invaded range will be allowed, or whether demand will need to be met exclusively from the United States. I would hope that imports from the Caribbean and Central America will be not only permitted, but indeed promoted.

WHAT A RIDICULOUS TYPE OF BAN

Perhaps also including two additional lines in the bill would both help make it clear that the source of these fish is still unknown and further protect our coast. 1. Public and private aquariums with open water systems plumbed to the ocean may not have breading lionfish. (While there may no longer be any this should be a law so legal action can be taken if some moron decides to setup something like this again. It also spreads the blame as this law should.) 2. A team should be assembled to look into a. If it is possible for larvae to travel in a ballast and b. If there are additional procedures or equipment that could make sure that larvae from abroad cannot ever travel in ballasts. (Further spreading blame, further protecting our native waters)