Of urchins and amphipods and of beauty and bugs

Text & Images by Ronald L. Shimek, Ph.D.

People who have read more than one of my musings generally are aware I like to discuss things that aren’t what they seem to be. And particularly, I like to discuss things that seem to be very obvious, but actually are more oblivious than obvious. So putting this all together, I like to discuss interactions that are obviously what they aren’t.

A good case in point revolves around the large Red Sea Urchin of the Northeastern Pacific, Strongylocentrotus franciscanus. These are sea urchins that are far larger than the common sea urchins of reef aquaria. Excluding the spines, the test or skeleton of this animal can reach up to 15 cm, and the spines are up to 8 cm long, giving a spine-tip to spine-tip diameter at its widest of about 30 cm (1 foot).

At places throughout the Pacific Northwest, there are, or were (harvesting them has taken quite a toll), huge beds of these urchins where the animals created a solid urchin layer over the substrate. Sea urchins being sea urchins, they maintain themselves by eating anything they can bite off the bottom and ingest. Referred to as being herbivorous animals, in these dense assemblages they eat anything and everything they can catch. Decades ago when I was beginning my marine investigations, which I have loosely termed “research,” these dense assemblages of Red Urchins were presumed to be normal components of the subtidal fauna. In the years since, it has become apparent that they are artifacts of humanity’s slaughter of the sea urchin’s major predators, the sea otters. With no sea otters to control their numbers, the Red Urchins became their own plague.

However, that’s another story.

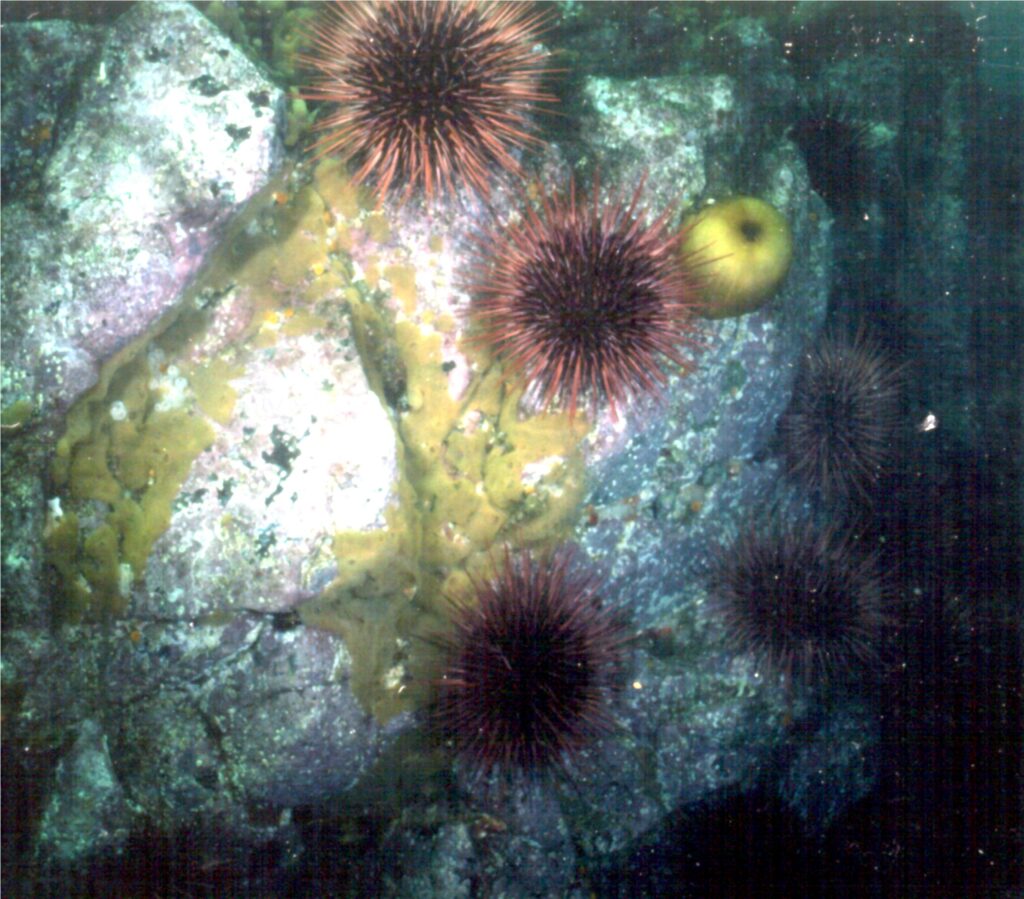

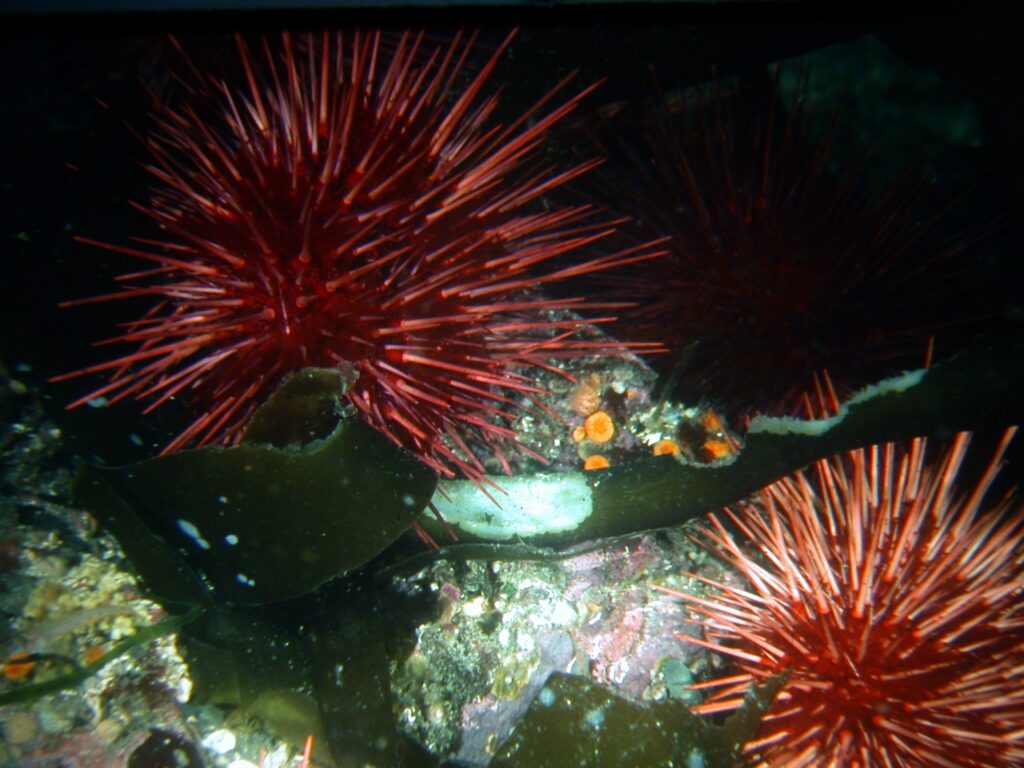

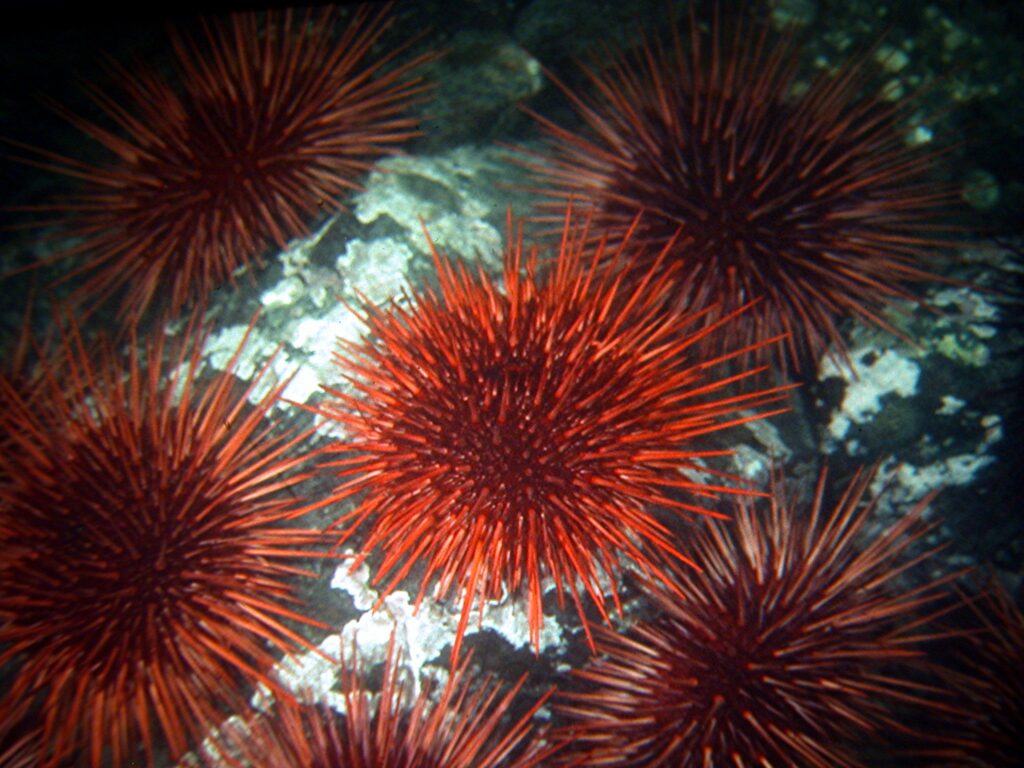

The illustrated introduction of this short photo essay is the collection of four images below which show the Red Sea Urchins, as they are commonly perceived. Note how nice and clean the urchin spines are. Unlike the long-spined sea urchins found in reefs and occasionally in reef tanks, the Red Urchins do not have particularly dangerous spines. The spines are not very sharp and lack any venom system.

A dense assemblage of Red Urchins, from the Canadian west coast, grazes the life off rocks, leaving only toxic sponges, sea anemones, and some coralline algae.

- A dense bed of Red Urchins found in years past from northern Puget Sound.

These Red Urchins are eating kelp they caught and pulled to the bottom. The cavity in the kelp is filled with a gas and normally keeps the algae floating above the urchins, but the kelp fronds can get long enough to reach the bottom, and if the urchins grab on, they can pull the kelp down and eat it.

These Red Sea Urchins are animals. Not a surprise! :). However, when abundant the urchins also become a substrate. And when their total surface area is calculated, it becomes apparent they can actually create a considerable area.

Unlike many other marine animals, sea urchins have only a thin, very fragile, epidermis, as many reef aquarists are aware. As a result, they must have some defenses to keep other animals from fouling their surfaces. The urchin body is covered by an array of small pinchers, called pedicellariae, many of which are venomous, and they bite anything that tries to land on the urchin’s body. They often do a good job of keeping the body clear of settlers. However, the pedicellariae, cannot reach up on the spines, and that is where some fouling animals take up residence.

Dulichia And Its Home.

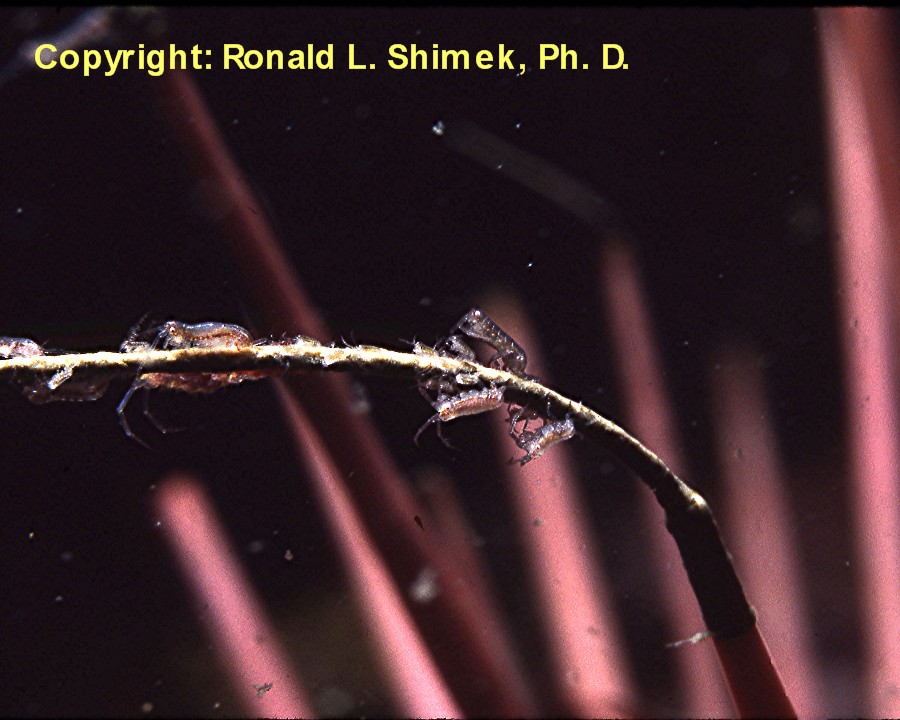

The Brown Strands On Some Spines Were Put There By The Amphipods Living On Those Strands.

Many of the Red Sea Urchins in any given environment are wholly clean of fouling organisms. However, some of them appear to have brown strands of material extending from the spine’s tip. A casual observer might think those strands are algal strands, perhaps.

But that observer would be wrong.

Those strands are mostly fecal material from an amphipod in the genus Dulichia, probably D. rhabdoplastis. The story begins when a pregnant female amphipod, carrying her brood of developing youngsters, takes off from its ancestral fecal strand and strikes out for better pastures. If she finds an urchin spine that suits her, she will land on that spine’s tip and defecate, molding its feces into the primary, basal, amphipod fecal patty.

Adult Female Dulichia cf. rhabdoplastis On Its Fecal Strand.

The adult amphipods have large antennae with large bristles, or setae, on them. They climb up on their strand and wave their antennae around in the water currents to catch plankton which are eaten… processed… and pooped out and thence added to the strand. As the strand grows, the female starts to glean its surface, collecting and eating microalgae from the surface in addition to the plankton. Analogous to the proverbial destination of roads in olden times when all roads led to Rome, all Dulichia food eventually leads to the strand.

A Dulichia Female On Her Fecal Strand.

A Dulichia Female And Some Of Her Young From A Couple Of Broods.

As the female grows and matures she will mate, producing many broods all of which live on and add to their communal crappy house… Eventually some larger females will take off and try to find a new strand or other place to live. Amphipods lack free-swimming larvae, and the mother carries and cares for her developing offspring in a brood pouch similar in function to a marsupial’s pouch.

Some Urchins Can Become A Veritable Amphipod Metropolis With Dozens Of Fecal Strands And Many Hundreds Of Amphipods.

- A Dulichia Female On Sediments Of Cowlitz Bay, Waldron Island, Northern Puget Sound.

Dulichia individuals also are commonly found building their fecal strands on sand bottoms. I don’t know if this is the same species that lives on the urchin spines. Although I have treated them as the same in this post, there may be some differences other than habitat choice. However, I am not an amphipodiatrist, so for me… a Dulichia is a Dulichia is a Dulichia is a bug.

Temperate Rainforest Slime Mold Fruiting Bodies

Author’s Note

To folks who wondered what happened to this blog over the last few months. Well, I have wondered that, too. I have been fighting some severe (read that as a @%^$$@& AWFUL) back pain for the last year or so. I hope I am now getting my Mojo back and I hope to post here regularly soon. I can’t thank the folks here at R2R especially Matt Pedersen and James Lawrence enough for understanding and allowing me to keep this irregular schedule.

Welcome back Ron. I have been missing you on Marine depot forums as well as Eric Borneman and Anthony Calfo. I miss your writings, your help with identification and expertise in so many ares. I thought there was somewhere to still contact you for questions, but was unable to find it. I am happy and comforted that you are still sharing your knowledge.

Fascinating. Next time I see Red urchin with strands, I will have to take a closer look.

As always, your musings are not only entertaining, but educational as well.