By Daniel Knop

Web Bonus Content from the September/October 2013 Issue of CORAL Magazine

Additional Bonus Brittle Star Articles

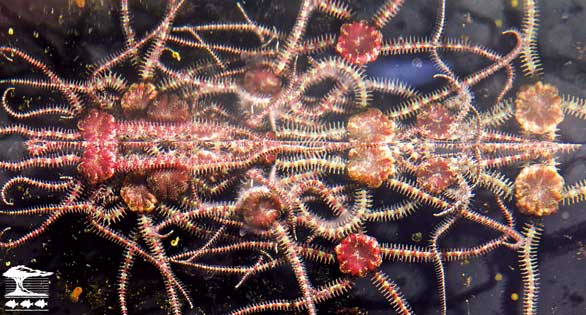

Spider-like, they emerged from all cracks and crevices. It looked almost like an alien invasion in a science fiction movie. Countless arms waved through the water, probed the environment, and attached themselves to rocks to pull themselves up. Each individual wanted to be first, to find the best place. The urge of a brittle star to climb—from the rock structure, up the aquarium glass, to the surface—is so powerful that some specimens came out of the water, standing on the bodies of their fellows. With almost blind zeal, half a hundred of these echinoderms assembled, as if following a secret command. However, it was not blind obedience or fear that drove them, but the irrepressible wish to reproduce: a brittle star wedding was imminent!

Unlike other invertebrates that mate and exchange their genetic material directly, free spawners must synchronize their germ cell release. Therefore, they need a trigger that sets in motion the complex reproductive process. For these brittle stars, often referred to as Ophiocoma pumila in the hobby, that trigger is a sudden change in the environment—in this case a partial water change. As soon as the fresh sea water had flowed into the aquarium and mixed with the old water, the first arms stretched out from under the rocks. Within moments the aquarium, which had shown no sign of a brittle star before the water change, was teeming with them. These animals normally hide during the day and come out at to scavenge at night, but now they suddenly moved out into the open, despite all the dangers, to comply with their biological directive: reproduction.

While most brittle star species are dioecious, some are hermaphroditic. Some free-spawning hermaphroditic species exclusively release sperm, while the oocytes remain in the body and are fertilized by the sperm of other individuals. The larvae of these hermaphroditic breeders remain in the respiratory cavities, or bursae, and mature there.

On each side of the armpit on the oral side there are slit-shaped genital openings to the bursae—sac-like invaginations that are usually used for respiration. The animal reduces its volume by contracting the oral disc muscles to eject water and increases its volume by breathing in oxygen-rich water. The bursae also contain the gonads. Here, the sperm mature and are stored in a low-liquid form. During spawning, the gonads empty the sperm into the bursae, which serve as reservoirs. The germ cells are diluted with water, so the amount of sperm that finally emerges through the openings at the bases of the arms appears to be very great.

This is a typical posture: the oral disc is raised to squeeze the sperm out through the genital slits.

In seemingly endless swells, this white mass exits through the genital slits, drips down, and forms elongated streaks in the open water. In contrast lighting, the five or six-armed stars look like comets with white tails. The sperm gradually mixes with the surrounding water to form a homogeneous, whitish mist that envelops everything.

Within about an hour, most of the 50 brittle stars had released sperm. Some had remained near their hiding places in the typical spawning posture, with exposed oral discs. However, most of the small echinoderms had taken the more daring path, climbing up to the water’s surface in order to ensure that their own genes were spread as widely as possible. Some in top form unloaded huge masses into the 16-gallon (60-L) aquarium. The turbidity was significant, but none of the other aquarium animals developed signs of a lack of oxygen or other discomfort. The skimmer continued to work normally and showed no tendency to bubble over. A short time later, the tiny reef had returned to normal and there was no sign of the brittle stars’ “white wedding.”