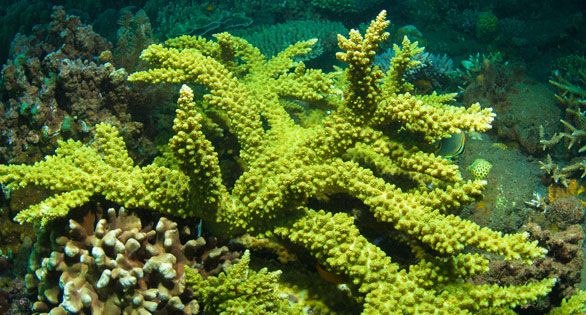

Branching Acropora displays vivid green fluorescing proteins when conditions are ideal. Loss of intensity can predict bleaching or growth retardation. Wild colony, Bali.

A new study by Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego scientists has revealed that fluorescence, the dazzling but poorly understood glow produced by many corals, can be an effective tool for gauging their health. The researchers suggest that measuring the intensity of fluorescence in stony corals could be a non-invasive test to be used when assessing the effects of weather events that stress corals.

As described in the March 12 edition of Scientific Reports (a publication of the Nature Publishing Group), marine biologists Melissa Roth and Dimitri Deheyn describe groundbreaking research using fluorescence to test coral stress prompted from cold and heat exposure.

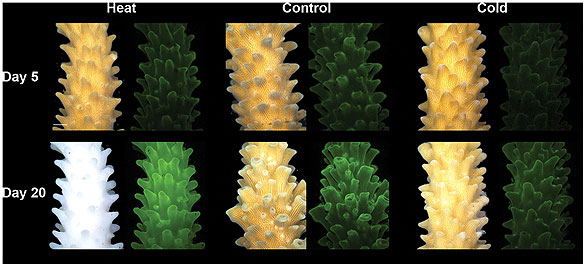

In experimental studies conducted at Scripps, Roth and Deheyn tested the common Indo-Pacific reef-building branching coral Acropora yongei, known in the aquarium trade as the Bali Green Slimer, under various temperatures. Test groups were subjected to 5-degree C water temperature changes (both warmer and cooler) conditions.

Representative Acropora yongei samples from different treatments and time points during temperature change experiment. Each sample includes an image under white light (left panel) and blue light (excitation 470 ± 40 nm and longpass emission filter ≥500 nm; right panel); the same coral sample from each treatment is shown through time. Scale bar represents 2 mm. Photo credit: Dimitri Deheyn and Peter Kragh.

Branching corals are susceptible to temperature stress and often one of the first to show signs of distress on a reef. Roth and Deheyn found, at the induction of both cold and heat stress, corals rapidly display a decline in fluorescence levels. If the corals are able to adapt to the new conditions, such as to the cold settings in the experiment, then the fluorescence returns to normal levels upon acclimation. While the corals recovered from cold stress, the heat-treated corals eventually bleached and remained so until the conclusion of the experiment.

Coral bleaching, the loss of microscopic symbiotic zooxanthellae that are critical for coral survival, is a primary threat to coral reefs and has been increasing in severity and scale due to climate change. In this study, the very onset of bleaching caused fluorescence to spike to levels that remained high until the end of the experiment. The researchers noted that the initial spike was caused by the loss of “shading” from the symbiotic algae.

Reef-building corals create an oasis of life and diversity in a sparse ocean. Because branching Acropora corals such as those pictured here in the Central Pacific are in peril from climate change, the whole ecosystem is in danger of collapse. (Credit: Melissa Roth)

Branching and table-top corals of the genus Acropora dominate coral reef ecosystems such as those pictured here from the Indo-Pacific. Branching corals are amongst the most sensitive to temperature change and often the first to bleach under stress. Photo credit: Melissa Roth “This is the first study to quantify fluorescence before, during, and after stress,” said Deheyn.“Through these results we have demonstrated that changes in coral fluorescence can be a good proxy for coral health.”

Deheyn said the new method improves upon current technologies for testing coral health, which include conducting molecular analyses in which coral must be collected from their habitat, as opposed to fluorescence that can be tested non-invasively directly in the field. Corals are known to produce fluorescence through green fluorescent proteins (GFPs), but little is known about the emitted light’s function or purpose.

Branching and table-top corals of the genus Acropora dominate coral reef ecosystems such as those pictured here from the Indo-Pacific. Branching corals are amongst the most sensitive to temperature change and often the first to bleach under stress. Photo credit: Melissa Roth

Scientists believe fluorescence could offer protection from damaging sunlight or be used as a biochemical defense generated during times of stress. “This study is novel because it follows the dynamics of both fluorescent protein levels and coral fluorescence during temperature stress, and shows how coral fluorescence can be utilized as an early indicator of coral stress” said Roth, a Scripps alumna who is now a postdoctoral scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and UC Berkeley.

The National Science Foundation (NSF), an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research’s Natural Materials, Systems and Extremophiles program supported the research. Birch Aquarium at Scripps provided the corals and technical support for the experiments.

ABSTRACT

Widespread temperature stress has caused catastrophic coral bleaching events that have been devastating for coral reefs. Here, we evaluate whether coral fluorescence could be utilized as a noninvasive assessment for coral health. We conducted cold and heat stress treatments on the branching coral Acropora yongei, and found that green fluorescent protein (GFP) concentration and fluorescence decreased with declining coral health, prior to initiation of bleaching. Ultimately, cold-treated corals acclimated and GFP concentration and fluorescence recovered. In contrast, heat-treated corals eventually bleached but showed strong fluorescence despite reduced GFP concentration, likely resulting from the large reduction in shading from decreased dinoflagellate density. Consequently, GFP concentration and fluorescence showed distinct correlations in non-bleached and bleached corals. Green fluorescence was positively correlated with dinoflagellate photobiology, but its closest correlation was with coral growth suggesting that green fluorescence could be used as a physiological proxy for health in some corals.

Journal Reference

Melissa S. Roth, Dimitri D. Deheyn. Effects of cold stress and heat stress on coral fluorescence in reef-building corals. Scientific Reports, 2013; 3 DOI: 10.1038/srep01421