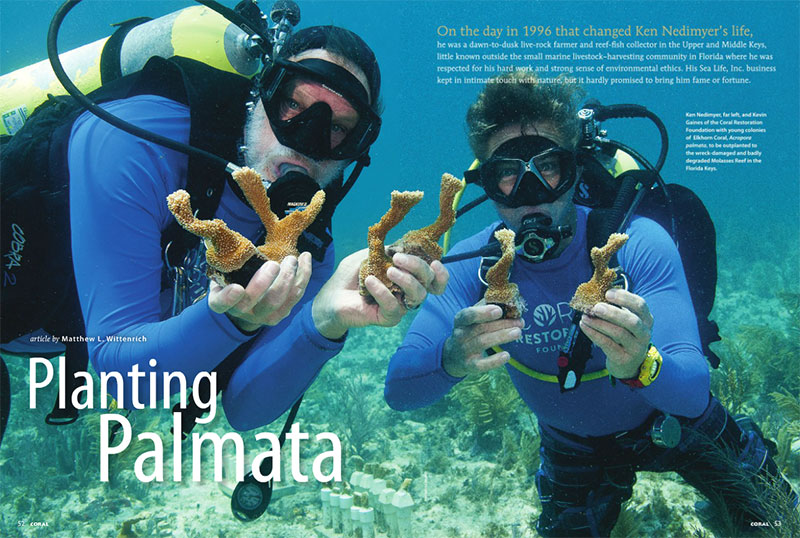

Ken Nedimyer, left, and Kevin Gaines of the Coral Restoration Foundation with young colonies of Elkhorn Coral, Acropora palmata, to be outplanted to the wreck-damaged and badly degraded Molasses Reef in the Florida Keys.

The following is a partial excerpt from the September/October 2012 issue of CORAL Magazine

by Matthew L. Witternich

On the day in 1996 that changed Ken Nedimyer’s life, he was a dawn-to-dusk live-rock farmer and reef-fish collector in the Upper and Middle Keys, little known outside the small marine livestock–harvesting community in Florida where he was respected for his hard work and strong sense of environmental ethics. His Sea Life, Inc. business kept in intimate touch with nature, but it hardly promised to bring him fame or fortune.

On this day, in 30 feet of water off Tavernier, Nedimyer was gliding slowly over his neat rows of aquacultured rock, which had been collected dry from an upland quarry on Grand Bahama Island and from the Florida mainland. After two years submerged on the sandy bottom, the porous “Miami Oolite” limestone rock was nicely encrusted with coralline algae, green macroalgae, sponges, bryozoans, and other invertebrate life. Thinking about how the crop of rock was almost ready for harvest, Nedimyer was suddenly stopped in his watery tracks by something he had never seen here before: settled recruit colonies of Acropora cervicornis, Caribbean Staghorn Coral.

Once a dominant stony coral in Florida and Caribbean waters, this species, along with Elkhorn Coral, Acropora palmata, had become increasingly rare and would soon be protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Collecting or selling these species would be forbidden within a year or two, although neither had ever sold in the aquarium trade.

Nedimyer left the young Staghorns untouched, but the notion that this important reef-building species was reproducing itself in his backyard became a preoccupation. Could this phenomenon be used to help repopulate barren reefs that had lost their Acropora cover to storms, pollution, weather events, and disease?

“After attending the Marine Ornamentals Conference in Orlando in 2001, I was inspired to start fragging the corals we had growing on the live rock site,” Nedimyer recalls. “My daughter Kelly and I even turned it into a 4-H project, with some help from her sister Kara.”

Unlikely Hero

Today, Nedimyer is president of the Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF) and has, in recent years and months, been called many things: a “pioneer environmentalist,” “hero to the reefs,” and “real-life aquaculture action hero.” Most notably, he was a named one of the 2012 class of global “CNN Heroes.”

Such praise makes Ken Nedimyer uncomfortable, but it is well deserved. Over the last decade Nedimyer and his crew have outplanted more than 3,500 corals to help rebuild the reefs of the Florida Keys, established several ocean nurseries growing more than 25,000 corals, and created perhaps the greatest working example of reef restoration anywhere in the world. Their model has triggered an onslaught of successors and collaborators such as Nova Southeastern University, the University of Miami, Mote Marine Lab, The Florida Aquarium, and The Nature Conservancy, among others.

“Ken has demonstrated that one person can make a difference and instills hope for the future of our reefs,” says Kevin Gaines, operations manager of CRF. When confronted by such praise, Nedimyer offers a humble smile: “ I don’t consider myself a great scientist or a great aquaculturist, but I think my life experience as a scientist, rock farmer, aquarist, and marine life fishermen has given me a unique set of skills that are necessary to turn this idea into reality.”

Once a workaday fish collector, Nedimyer has become head of a tax-exempt non-profit organization that has garnered multi-million-dollar support from The Nature Conservancy and a growing number of corporate sponsors in the marine aquarium industry. (The family company, Sea Life, Inc., has been passed down his daughter Kara, who is operating it as KP Aquatics with her husband, Phillipp Rauch.)

READ the full article in CORAL Magazine. Purchase a hard copy back issue of the September/October 2012 CORAL Magazine here.

Opening spread featuring Ken Nedimyer and Kevin Gaines copyright Tim Grollimund.