Originally posted: 18 May, 2011

CORAL Talks with Marinelife Pioneer Henry Feddern

By Ed Haag

Since the origins of skilled labor, every organized profession has had its icons. They are the exceptional souls whose high standards, leadership, and ethics are indelibly embossed on their chosen calling.

Rarely timid, these dedicated individuals educate, inspire, and, most important, by their own example help shape the way others in their profession perform. For better or worse, the ways in which these icons represent their industries have consequences that last far longer than a single generation.

A commercial fish collector whose career spans over five decades, Henry Feddern was there in the beginning of the marine aquarium hobby. He was one of a tiny cadre of aquatic mavericks squeezing out their living by introducing their exotic catches into a radical saltwater trade still in its infancy.

In the context of this now seven-billion-dollar global industry, Feddern’s contribution to establishing the fish-collecting ground rules for his home state of Florida, and beyond, is undeniable.

“His name might not be on the lips of every aquarium store owner, but Henry’s contribution to this state’s fish collection industry is huge,”says former livestock collector turned reef-restoration advocate Ken Nedimyer. “For much of my career Henry has been the face of our industry.”

Nedimyer, who heads up the Coral Restoration Foundation in Tavernier, Florida, adds that to this day, Feddern remains true to his own vision. While the industry has seen explosive growth, and with that growth have come opportunities to expand his business, Feddern still runs a one-man Florida Keys operation that markets through word-of-mouth to a select group of long-time customers.

“The fact that Henry is still a low-profile collector and seller of Florida marine life is no accident,“ says Nedimyer. “Above all, Henry loves to dive, and he knows that if you are managing a building full of employees you don’t do much diving.”

Feddern fits perfectly in the classic school of loner marine biologist collectors, the most famous being Ed Ricketts, who served as the model for “Doc” in John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row. Among the more contemporary biologist–marine organism characters doing in literature what Feddern does in real life is “Doc Ford,” the protagonist in a bestselling series of novels by Randy Wayne White set in Sanibel and Captiva Islands.

Feddern himself could easily be called “Doc,” although he is just affectionately “Henry” to his colleagues and customers. “I don’t encourage people to call me “Doc”—I don’t want to explain that I can’t write them a prescription,” he says.

Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1938, Feddern accepted a scholarship to the University of Miami after graduating from high school. Upon receiving his Ph.D. in marine biology and after a brief stint as a researcher for an aspiring aquaculture firm, Feddern settled into his career as one of Florida’s first full-time commercial fish collectors.

In the early 1970s, he joined with a handful of other commercial collectors to form the Florida Marine Life Association (FMLA), a trade organization representing this new and growing industry. In 1988, the same group petitioned the Florida Marine Fisheries Commission to adopt standards for the collection of tropical marine life—including a call for state regulation, licensing, and catch limits.

“Such a request was unprecedented,” says Jessica McCawley, state administrator for the Division of Marine Fisheries Management. “No other fishery in the state of Florida ever asked to be regulated.”

For McCawley, it was the beginning of a shared commitment by fish collectors and state fisheries regulators to create a sustainable live marinelife fishery. “Henry, with his science background, has been invaluable in helping shape policy,” she says. “In one capacity or another he is always at the table. Without his efforts and [those of] others like him we would not be where we are now.”

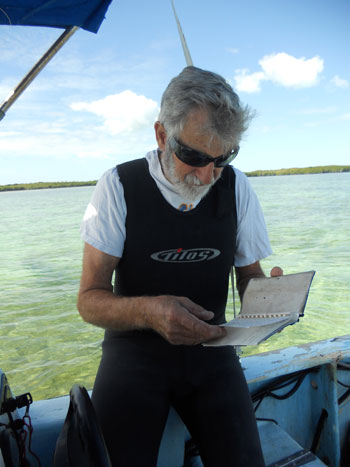

CORAL caught up with Henry and his wife, Gail, at their residence on Key Largo, the last house on a road that stops at a natural tidal creek leading from the open ocean into a small saltwater lake nearby. With his 20-foot (6.1-meter) dive boat tied to a dock next to the house, a fruiting Key lime tree in a pot on the deck, and honeybee hives in the front yard, it is a setting as close to paradise as a nature-loving fish collector could hope for anywhere on this planet.

CORAL: You were raised in Poughkeepsie, New York. That is a long way from the coral beds of the Florida Keys. What got you interested in fish and marine biology?

Henry Feddern: I grew up in the countryside with a small river at the back yard, and a small municipal airport beyond that. A tiny stream on the neighbor’s property flowed into the river over a waterfall. I built a rock enclosure under it and kept the minnows I collected in there.

Later I kept a freshwater aquarium. I had the usual Neon Tetras and all those other tropical fish that were available then. I also had an Oscar that I traded to another kid. A month or so later he begged me to take it back. The Oscar was eating all his other fish.

Feddern with Red Tree Sponges in his Tavernier, Florida, holding facility. All organisms are collected to fill orders from public aquaria, universities, and wholesale and retail clients.

As a teenager I had a saltwater aquarium. I got it when they first came out with the Instant Ocean salt mix. I believe the manufacturer was in White Plains, New York. I remember the first saltwater fish I got was a Sargassum Frogfish, Histrio histrio.

CORAL: How did you get started in the fish collection business?

Henry Feddern: When I went to the University of Miami, I had a scholarship but it just paid tuition. That meant I had to work in the evenings in the supermarket to cover part of my room and board. On the weekends I was free, so I would go down to the Keys and catch angelfish for a wholesaler in Miami.

CORAL: How did you transport the angelfish you caught?

Henry Feddern: I had a Triumph Thunderbird motorcycle. I would put the fish in a 5-gallon, wide-mouth glass jug and secure it to the buddy seat with straps.

CORAL: Being a full-time student and working on weeknights in a grocery store and then spending your weekends running down to the Keys on a motorcycle to collect fish—that sounds like an exhausting schedule.

Henry Feddern: I did fall asleep once and ran off the road. I was wearing a bathing suit with my fins and mask in the buddy seat. Fortunately, I didn’t break the jug, but I did skin my knee and I broke my jaw. For the next month I couldn’t dive because my teeth were wired shut. That also meant I was drinking my dinners through a straw.

CORAL: After school and a taste of corporate life, how deliberate was your decision to spend your life collecting for aquarists?

Henry Feddern: I like to be outside and part of nature. To me, every time I dive it is like going on safari into another world. My other options couldn’t compete with that.

CORAL: Is your Ph.D. any use to you in your capacity as a fish collector?

Henry Feddern: It helps with my credibility when I work with other scientists. When I speak their language they are more likely to take me seriously. That is of great help when I work with government agencies. My Ph.D. also helps me with fish collecting. Since I better understand the fish’s life history and behavior, I can then design nets to efficiently catch them, and know more about how to care for them in captivity.

CORAL: You are out on your boat in the ocean collecting two to four times a week, usually alone. Do you ever have any concerns for your own safety?

Henry Feddern: Not really. I have been collecting long enough that most everything that could happen has happened, except for the bends. I never got the bends.

I actually feel safest when I dive alone, and there is no one to distract me. Then I can rely on my routine. It is difficult to find someone with enough experience, and a neophyte can be awfully dangerous.

The Feddern Home on Plantation Key: a 20-foot collection boat at the dock and honeybee hives in the yard.

CORAL: How does today’s dive technology compare with the equipment you used as a young collector?

Henry Feddern: The equipment we have today is a lot safer and easier to use. Back in the old days you could not pant with a regulator. It would not give you enough air. The new regulator will give you what you need.

CORAL: You have been a professional fish collector for over 50 years. In what other ways has the business changed?

Henry Feddern: In the beginning, the aquariums were just sterile fish tanks with a bit of sand sprinkled on the bottom. Then we started putting gorgonians, invertebrates, and even some corals into the mix. Now we use live rock and live sand to build reef aquariums that support even the most delicate kinds of marine life.

CORAL: What species do you collect these days? Which are most popular?

Henry Feddern: I sell a lot of gorgonians and a lot of Lookdowns, Selene vomer. All my collecting is done after the orders are in. That way I can get them fresh from the ocean and ship them right away.

CORAL: What’s the strangest creature you have ever collected?

Henry Feddern: I would say a bright orange frogfish. It didn’t look at all like a fish. In fact, it looked more like a piece of sponge. I was looking under a rock and I put my hand next to a sponge and the sponge moved. I immediately knew what it was, so I caught him.

CORAL: You’ve live-shipped your marine specimens all over the planet. What are some of the methods you have adopted to assure survival?

Henry Feddern: It is pretty straightforward. Most shipping bags are about 10 inches tall. You have the bag that holds the fish and then an outer bag that fills the entire container. The fish goes in the inner bag with about an inch of water—just enough to allow the fish to swim upright and keep it calm. Oxygen is then pumped into the rest of the shipping bag. That saturates the water and keeps it saturated for a couple of days.

In the summer you put a little ice between the outer and inner bags. That reduces the temperature of the water 5–10 degrees, and the fish uses less oxygen. When the water temperature reaches about 80 degrees, that is when I start using ice.

CORAL: You were one of the founding members of the Florida Marine Life Association (FMLA) and you are its current president. How do you answer critics who charge that the aquarium collection trade is completely unregulated?

Henry Feddern: That is absolutely false. Collecting marine species is regulated very carefully by the state of Florida. In fact, we are more heavily regulated than any other Florida fishery. Members of the FMLA have encouraged this to counter any environmentalist’s claim that we are raping the reefs.

We have catch limits based on surveys and a licensing policy that says that if you want to collect fish commercially, you have to buy an existing license. No more new licenses are being issued by the state of Florida.

CORAL: Other critics have accused Florida marine life collectors of overharvesting certain species, including gorgonians and aquarium maintenance animals. Do you feel the claims that collectors are pushing certain marine species to “collapse” are justified?

Henry Feddern: The state of Florida conducts its own surveys on the harvest of collected species based on catch per unit effort (cpue) so they can tell when and if a species is decreasing, and they will change the regulations to compensate for that.

As far as the gorgonians go, we are collecting about 35,000 a year over the entire Florida Keys and off Florida’s east and west coasts. Based on counts of the number of gorgonians per square meter, it is estimated that in the Florida Keys alone there are between 8 and 8.5 billion colonies. In this case we are taking probably one out of half a million.

Because of the rapid reproduction and growth of gorgonians, harvesting this number of gorgonians probably has the same effect on the gorgonian population as plucking a few blades of grass has on a typical lawn. I can’t see that there is any possibility of overharvesting gorgonians.

CORAL: Andrew Rhyne, Ph.D., suggests that certain invertebrates, such as Blue-Legged Hermit Crabs, Peppermint Shrimp, Astrea spp. grazing snails, and others, are being overcollected for aquarium maintenance.

Henry Feddern: As much as I believe he is probably sincere, Rhyne is engaging in scare tactics. I read his article, and it is long on speculation and short on hard data. As a scientist, I see a scare story with no facts to back it up.

Gorgonians are among the most popular items Feddern offers, including this Pinnate Spiny Sea Fan, Muricea pendula.

CORAL: Eric Borneman has also pointed to the declining harvest of Giant Sea Anemones, Condylactis gigantea, as proof of overharvesting. Is this species in need of collection limits?

Henry Feddern: That is very possible. We have been working with the state of Florida on collecting limits. It could very well be that they need to change them again. You have to remember there might be other factors in play here. The “big freeze” in 2009 did major damage to these critters. They could be slow coming back.

CORAL: Now for the other side of the coin. With existing restrictions on the issuing of new commercial licenses, is there any way someone interested in a career collecting aquatic specimens can break into the business today?

Henry Feddern: Sure. Each person with a Marine Life License can obtain a vessel license, which means that an unlicensed person on the boat can collect under that existing license. Someone who is interested in collecting can break into the field as an apprentice. That allows him or her to learn the proper techniques of collecting. The apprentice can continue being a partner, or can buy a license from someone leaving the business.

CORAL: What do you see as the greatest threat to the aquatic ecosystems in the Florida Keys?

Henry Feddern: It changes. Sewage and septic tanks used to be a major problem, but we are gradually getting that under control. Now I believe it is nitrates coming down through the Everglades and phosphates coming down the west coast from the phosphate mines. Phosphates and nitrates combine to create the perfect environment for algae blooms. A couple of years ago, algae blooms killed a lot of stuff in Florida Bay.

CORAL: Is there anything you would do differently in your life if you had the chance to start over?

Henry Feddern: Nope. I am in a business that I enjoy. I love it when people pay me to do what I enjoy.

Ed Haag is a CORAL contributor living in Spokane, Washington. Henry Feddern can be reached at hunter(at)terranova.net

I am trying to reach Henry Feddern. We were students together in U or Miami Marine lab it the 1960s.I see that the interview was done in 2011 so maybe the address you gave for him, which I have tried, may no longer be valid.

Jonathan, I’ve sent messages through two avenues I have for him and included your info. Perhaps you’ll be able to connect.